views

However, not everyone realizes that anybody may write proposed legislation, in the hope of having it become law. This is a lengthy process that requires a great deal of research, dedication and effort. You also need to generate public support and, ultimately, get one of your Congressional representatives to accept the bill that you have written and introduce it to Congress.

Determining the Need for a New Law

Look for a national need. When writing a bill for the U.S. Congress, you must understand that you are proposing a law that will take effect over the entire country. To generate the support that is needed in order to pass, you will need an issue that has nationwide appeal. Read national newspapers and watch national news broadcasts to find issues of wide interest and importance. Issues that affect everyone in everyday life are good candidates. For example, you might consider topics related to our national food supply, energy use, national security or other general topics of concern.

Determine the needs of your local constituents. You must also realize that your local Representative or Senator will need to champion your cause and introduce your bill in Congress. Therefore, the topic must be something that generates strong enough local concern to catch the attention of your legislator. If you can generate strong local support, then you will be more likely to convince your legislator that the bill is important enough to introduce into Congress. For example, if your state has a major fishing industry, a law that limits pleasure boats in designated fishing waters would probably be supported by many residents of your state. Consider setting up an online petition or survey tool to measure public opinion on your question.

Select a topic that you are passionate about. To do the job well, you will be devoting many hours to research, writing and lobbying on your bill. Select a topic that you believe in entirely. Your passion for the subject will carry through to your writing and will help generate support among other people. You may also base the bill on your own personal experience or expertise. For example, if you are the parent of a special needs student, research special education laws, then draft a bill that enhances the required services for such students.

Researching the Issue

Gather data about the topic. You are going to need to know everything you can about the topic before you can present a bill to Congress. Use any available resources that you can to learn about the issue. Research the problem, as you see it currently, and gather data and statistics. Investigate possible solutions and try to determine what costs would be associated with the solution that you are proposing. Start your research with a reference librarian at your public library. From there, you can investigate specialized sources of information, visit law libraries, or speak with experts in the field.

Speak with community members. Part of your research can be in the form of public opinion. As you learn more about the topic, you should try to find out how much of the general public identifies the same issues and concerns that you have. Any of the following can be useful ways to gather public opinion and support: Conduct informal gatherings of neighbors. Organize a small town meeting at a community center, church or library meeting room. Ask to speak at meetings of your local school PTA, civic organizations, chamber of commerce or other organized groups.

Use social media to gather public opinions. Start a campaign on Facebook or Twitter. These are increasingly powerful tools for sharing your views with a nationwide audience. You can also use online petition tools to gather support. If you craft a well-worded online petition, you can get people to “e-sign” it and demonstrate that they hold the same beliefs you do. For example, the Attorney General of Massachusetts initiated a social media campaign to gain support for legislation that was being proposed for a law in that state. Gather data from your online presence, such as the number of signatures on your petition or the number of followers or likes that you get on social media. This data can help generate support among legislators.

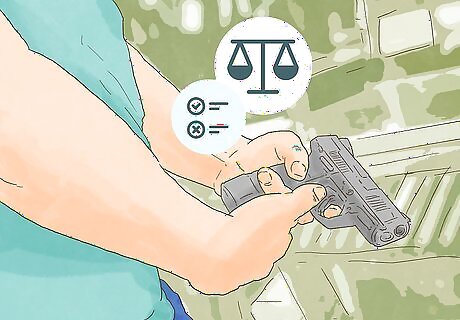

Talk with legislators. If possible, try to arrange an early meeting with your Congressional representatives. Even if your bill is not yet written, it can be a powerful beginning to discuss the topic with your elected official. If you can judge your representative's level of interest, you may gain some insight into the way to write your bill. For example, if you want to propose gun control legislation, but your representative is opposed to gun control, consider tailoring your bill to be more moderate. This may build stronger support for it.

Study current bills on similar topics. It can be helpful to understand how other bills before Congress are currently being treated. You don’t want to draft a bill that is very similar to something already exists. You can find out what topics gain attention and what topics to avoid. Some sources for such research include: Congress.gov is a free, publicly accessible database. It has information about committee debates, bills currently before Congress, and upcoming hearing schedules. You can find this information at www.congress.gov. National Journal is a source that provides current research and information on a wide range of political topics in and around Washington, D.C. You can find the access to the National Journal at www.nationaljournal.com.

Drafting the Bill

Identify your bill by a strong title. The title is the first part of your bill that will catch people’s attention and immediately begin to generate interest. If you construct a positively worded title, you can build support before people even get to the text of it. For example, a bill titled “A Bill in Favor of Increased Gun Control” may turn away many people. In contrast, the same issue presented as “A Bill to Improve Safety in Public Places” may garner more positive support.

Provide an introduction that states the purpose of your bill. In a brief statement, explain the objective of the law you propose. Other legislators who are considering your proposal will need to be able to read this one statement and envision voting for it. For example, the No Child Left Behind Act of 2002 gave as its purpose: “The purpose and intent of this title are to ensure that all children have a fair and equal opportunity to obtain a high-quality education.”

Explain the bill’s eligibility or exceptions. The next section of your bill should identify the individuals for whom the bill is intended, or for whom it is not intended. You will need to define the people who are covered by the proposed legislation. For example, a bill to propose a national minimum wage salary might state that it applies to “all workers who are legally employed within the United States, who have a valid permit to work in the United States, and who have not been convicted of any drug-related offense within the past six months.” Alternatively, you could define the bill’s application with a statement of exception, and define those who aren't covered by the proposed legislation. For example, a gun control bill might state, “The requirements of this legislation do not apply to members of any local, state or federal law enforcement agency.”

Provide definitions. Any terms that you include in your bill that will have a particular meaning should be listed and defined in this section. Even if you think that a term is self-explanatory, you should list it and give its definition. The definition section is also the place where you can include such restrictions as age, nationality, residence requirements and so on. For example, it is not unusual for a word as common as “individual” to be defined, particularly if an “individual” might include not only living people but also corporations, partnerships or other legal entities.

State the rules and other provisions. This is the real heart of the bill. This is the section that provides the requirements that you wish to propose. In this section you need to make your statements as clear and concise as possible, so there can be no confusion or misunderstanding about your intentions. Much of the debate that occurs with regard to a bill centers on this section. The length and organization of this section will depend on the complexity of your issue. A simple bill may be as brief as one sentence long. A more complex bill may need to be broken into sections and subsections. Plan the organization of your bill. Each main requirement should be written as a separate section and should be introduced using the labels "Section One," "Section Two," and so on. More specific, defining statements should be inserted as subsections.

Provide the bill’s effective date. Many laws do not become immediately effective upon passing and being signed by the President. In many cases, you need to allow some time for transition and preparation before a new idea becomes a requirement. For example, if you're proposing a change to the national minimum wage, requiring the change to take immediate effect would cause chaos for many businesses, who would need to make changes to payroll systems and budgets and determine how the new wage would change their workforce. It's common for a bill to include a section that says, “This legislation becomes effective six months after the date of enactment.” If no effective date is provided, then the bill becomes effective immediately upon being signed by the President.

Address issues of funding. It is generally understood that a bill that requires some act by the government will cost money. However, it is not appropriate for the bill itself to include its own budget. Budgeting the government is an entirely separate task. It is appropriate, however, for your bill to include language that might limit funding, either to a number of years or a specified amount of money. As an example, your bill might include an appropriations section that says, “Congress shall appropriate such funds as necessary for up to ten years from the date of enactment of this legislation.” This would limit funding for ten years, unless Congress takes additional action within that time to extend the provision.

Getting Your Bill into Congress

Contact your Congressional representative. You need to get the attention of your legislator for your bill to get to Congress. The first step is to reach out to your Representative or Senator to discuss the issue. You can find contact information for all federal elected representatives at the government site www.USA.gov/elected-officials. Follow the link to “Contact federal elected officials” to find your own Representative or Senator. The link will lead you to the legislators’ Washington, D.C., addresses and official email addresses. Legislators also have local, in-state offices. For this information, search directly for your legislator's name, or check your state’s official government website. Some representatives conduct open office hours specifically to meet constituents. If that is not available, contact your legislator's office and schedule a meeting. You may need to meet or speak with an aide first, however.

Present the need for your bill. When you can schedule a meeting, whether with your legislator or an aide, you should be ready with a brief presentation. You will need to convince your legislator that your bill is one that deserves to become a federal law. You should be prepared to discuss your research, any data you have collected, and the drafting that you have already put into preparing the bill. Understand that members of Congress and their staff have many demands on their time. You should present your information as concisely as possible, and then offer more detail if the legislator wishes to review it.

Be prepared for a long wait. After you get the bill that you have drafted into the hands of your Representative or Senator, the process for that bill to become a law is really only just beginning. The legislator will have to introduce the bill in Congress, where it will be discussed, debated, transferred to one or more committees, reviewed in more detail, edited, and eventually voted on. This is a very long process.

Comments

0 comment