views

The majestic tigers in India are much beloved creatures and at the same time feared too. The country’s national animal of late has been making news for reasons both good and bad. The positive story is the recently released findings of the fifth cycle of the All-India Tiger Estimation (2022) which put the number of these big cats in India at 3,167, a rise of two hundred from 2,967 reported in the 2018 Tiger Census, released in July 2019.

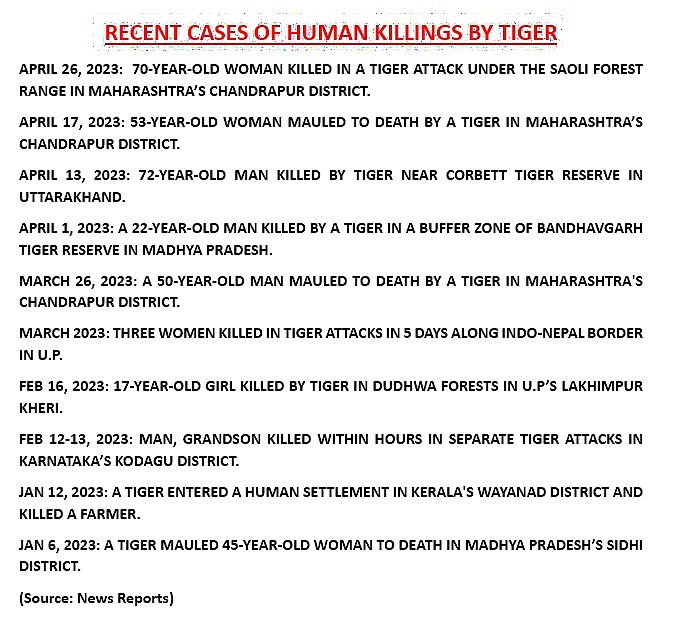

Here’s the bad news. Of late, reports of tiger-human conflicts leading to casualties have grown in number. This year alone so far there have been over 15 reported deaths of humans in encounters with tigers.

The maximum number of cases are from Maharashtra’s Chandrapur district. According to news reports quoting officials, eight persons have been killed in big cat attacks in the district since January this year. Last year, 53 people were killed in attacks by tigers and leopards here, home to the renowned Tadoba Andhari Tiger Reserve (TATR), while 14 tigers died in various incidents during the same period.

The killing of a young tribal boy and his grandson within hours of each other in separate tiger attacks in Karnataka’s Kodagu district in February this year made it to the international press. 12-year-old Chetan was mauled by a tiger while harvesting coffee at a plantation adjoining a forest. Hours later, his 75-year-old grandfather Raju was killed in a similar tiger attack within 500 metres of the previous incident. Both cases occurred close to the Nagarhole wildlife sanctuary buffer zone. The Hindustan Times reported that upon hearing the news, their 45-year-old female relative Jayamma was so shocked that she too passed away.

Congress leader Rahul Gandhi in February this year visited the family members of a 50-year-old farmer who was killed on January 12, 2023, in a tiger attack in his former Lok Sabha constituency Wayanad in Kerala.

In October 2022, forest officials in Bihar were forced to issue a shoot-at-sight order to kill an over three-year-old tiger which had turned a “man-eater”. The tiger had reportedly killed nine people living along the fringes of Valmiki Tiger Reserve in the West Champaran district within six months. Sharpshooters from the special task force team of Bihar police were involved to kill it. The victims of the killed tiger included a 16-year boy, a 35-year-old man, a 12-year-old girl, and a 40-year-old woman among others.

More recently, a video of a tiger charging at a tourist vehicle near Uttarakhand’s Jim Corbett National Park raised concerns among conservationists.

The pattern of killings by tigers is more or less similar across the country. The victims are attacked either when venturing into the wild to collect firewood or forest produce like ‘mahua’ or had gone to farmlands near the jungle to keep a watch on standing crops from wild animals. In some cases, the hungry wild animal enters human habitation in search of animals for their prey like pet dogs, cattle, etc. Sometimes the attack takes place when a person has gone out to answer nature’s call or even while sleeping in the open.

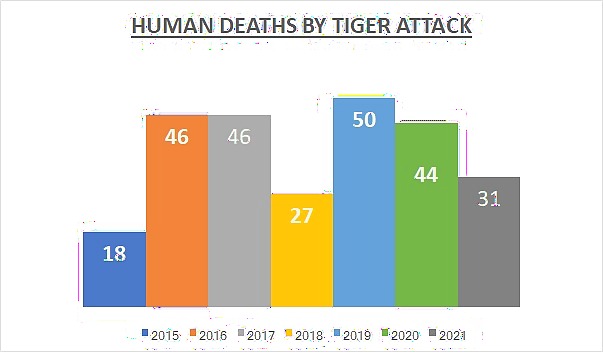

The government statistics given in Parliament over time has noted that between 2015 and 2021, 262 people lost their lives in tiger attacks across the country, with a maximum number of 50 deaths occurring in 2019. Among the states, Maharashtra recorded the highest number of 122 killings followed by 50 in Uttar Pradesh.

So, why is there a reported uptick in tiger-human conflict and the appearance of big cats in regions where they have not been sighted in recent times?

“Every wild tiger requires a prey base of 500 animals to sustain it. When prey becomes abundant, individual tiger territories shrink and breeding increases. A single female may produce 10-15 cubs in her lifetime, an average of one cub a year. Consequently, thriving tiger populations produce annual surpluses, pushing dispersing sub-adults and old tigers to the edges of reserves,” wrote Ullas Karanth of the Centre for Wildlife Studies, Bengaluru, in The Hindu.

“There is too much disturbance in tiger habitats under the label of eco-tourism and secondly tigers are running out of space within the successfully managed protected areas (PAs) and are being forced to move out into non-protected areas,” explains Debi Goenka, executive trustee, Conservation Action Trust (CAT), Mumbai. Goenka further blamed intruding developmental projects for the situation. “Wildlife corridors are being repeatedly destroyed by infrastructure projects.”

Explaining the sighting phenomenon, Indian Forest Service (IFS) officer Susanta Nanda further says: “Tigers have a long home range and dietary requirements. Increased tiger and human population, without an increase in the volume of tiger habitats, makes the competition for space intense among both, leading to conflict.”

“We have allowed their habitats to be degraded or destroyed. We have not been able to provide them with inviolate habitats,” says Goenka, expressing anguish over the failure to secure a protected and undisturbed environment for tigers.

Tigers inhabit an astonishingly wide range of habitats, including rainforests, grasslands, savannas, and even mangrove swamps. Regrettably, due to the rapid expansion of human activities, a whopping 93% of the tiger’s original habitats have vanished, according to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF).

Further, expressing discomfort over a recent Supreme Court order modifying its earlier order on eco-sensitive zones (ESZs) around national parks and sanctuaries, Goenka says: “Even the existing Protected Areas are under severe pressure. And even the Supreme Court is allowing the state governments to reduce the areas protected as ESZs.”

On April 26, 2023, the apex court issued a directive stating that its previous order from June 3 of the previous year, which required the establishment of a 1-kilometre eco-sensitive zone (ESZ) around protected areas, would not be applicable in instances where a draft or final notification for development had already been issued.

According to the recently released Status Of Tigers 2022 survey by the Centre, the population of tigers has increased by 200 to 3,167. Therefore, is the growing tiger population and added urbanisation placing a strain on their resources for survival?

“The carrying capacity of tigers in Indian forests as of now is estimated to be different by experts. The lowest is pegged at 4,000, while some put it at 10,000. Whatever it might be, the increase of 200 in numbers is definitely not stretching the resources now,” counters Nanda who is also the Principal Chief Conservator of Forests (PCCF) Nodal in Odisha.

“More than 30% of tigers are outside tiger reserves. Protection of tiger landscapes and the corridor between them can reduce the conflict to a greater degree,” suggests Nanda, when asked about ways to minimise big cats turning over to human-dominated landscapes for survival.

“We need to protect all the forests that we have left,” Goenka adds, echoing Nanda’s advice. “We need to stop linear projects cutting through forest areas. We need to provide suitable alternate employment and livelihoods to local people who live in and around tiger habitats.”

Wildlife experts and environmentalists have been raising concerns about linear infrastructures including power transmission lines, railways, roads, pipelines, and canals, arguing that these developments cause forest fragmentation and damage natural habitats, including large forested areas that are crucial for wildlife.

The tiger survey report too has expressed concern over the poor quality of protected areas for the big cats. “Most tiger reserves and protected areas in India are existing as small islands in a vast sea of ecologically unsustainable land use, and many tiger populations are confined to small protected areas. Although some habitat corridors exist that allow tiger movement between them, most of these habitats are not protected areas, and continue to deteriorate further due to unsustainable human use and developmental projects, and thereby are not conducive to animal movement,” the government report noted.

Besides, decorative shrubs like Lantana camara and Pogostemon benghalensis too have severely disrupted the food chain of wild animals. Lantana, a non-native plant, was brought into India some 200 years ago from Central America by the British. Today this invasive plant is ubiquitous across geographies from cities to the wilds, threatening over 40% of India’s tiger habitat, according to a study.

Not only does the poisonous Lantana plant spread quickly, but it also inhibits the growth of other plants and grasses. This triggers a destructive chain of ecological events that results in the migration of herbivorous animals and, ultimately, threatens the survival of India’s majestic tigers and other carnivorous species due to the looming possibility of starvation.

In the 50th year of the successful ‘Project Tiger’ programme, India can boast of increasing numbers of tigers. However, there is still much work to be done to maintain a delicate balance between humans and the big cats, ensuring that both can thrive harmoniously in their respective habitats.

Read all the Latest India News and Karnataka Elections 2023 updates here

Comments

0 comment