views

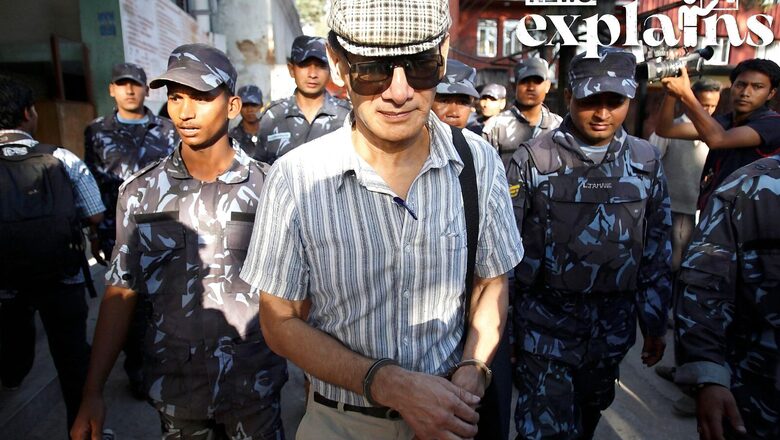

The release of Charles Sobhraj, a French national known as the “bikini killer” who police say is responsible for the deaths of over 20 young Western backpackers across Asia in the 1970s and 1980s, was ordered by Nepal’s Supreme Court on Wednesday.

But Who is Charles Sobhraj and Why is He Known as the Bikini Killer?

Sobhraj, 78, is the son of an Indian father and a Vietnamese mother. According to his associates, he is a con artist, a seducer, a robber, and a murderer.

In the mid-1970s, Thailand issued a warrant for Sobhraj’s arrest on charges of drugging and killing six women in bikinis on a Pattaya beach. He was, however, imprisoned in India before facing those charges.

In India, Sobhraj was sentenced to 21 years in prison on murder charges. After escaping from a prison in the mid-1980s, he earned another moniker, “the serpent,” for his ability to change his appearance. He was apprehended and imprisoned until 1997.

Following his release in India, Sobhraj returned to France. In 2003, he was arrested at a casino in Kathmandu, Nepal’s capital, and convicted of the murder of American backpacker Connie Jo Bronzich.

Sobhraj has denied murdering the American woman, whose body was discovered in a wheat field near Nepal’s capital. According to his lawyers, the charge against him was based on assumption. He was also found guilty of killing Bronzich’s Canadian friend, Laurent Carriere, several years later.

A Deeper Look Into the Killer’s Mind

In a report for the Guardian, Andrew Anthony recalled his experience ‘speaking with the serpent’ in 1997.

He encapsulated what has been known about Charles through various books and TV series: Sobhraj grew up in Saigon during the Vietnamese war of independence from France, the child of an affair between an Indian businessman-tailor and one of his Vietnamese shop assistants.

His mother then married an occupying French soldier, who returned to France with his young family, suffering from PTSD. Sobhraj did not settle in his new home and stowed away twice on ships bound for Africa.

He was a bright but delinquent adolescent who was drawn to crime – car theft, street muggings, and then holding up housewives with a gun. He spent the majority of his adolescence in and out of youth offender facilities, then their adult counterparts, in Paris. A well-meaning prison visitor helped him find work on the outside and introduced him to Chantal Compagnon, a bourgeois young Parisian. They fell madly in love. He promised her he was a changed man, and they got engaged, only for him to be arrested again for car theft.

But, like so many other women before her, she had fallen under his spell. When he emerged, they went on a wild crime spree across Europe and Asia. It was 1970, the start of the so-called hippy trail, when hordes of young people would travel through southern Europe, the Middle East, India, and the far east on a shoestring budget. It was a time of porous borders and lax security, when the only means of communication with home were letters that could take weeks to arrive, Anthony explains. A generation sought to rediscover itself by getting lost or high somewhere off the beaten path. Nobody paid attention to who came and went.

Sobhraj stole from unsuspecting travellers in this transient environment. But first, he was imprisoned in Greece, where he escaped by assuming the identity of his younger brother. He and Compagnon were later imprisoned in Afghanistan. They had just given birth to a daughter, who was sent back to Compagnon’s parents in France. Sobhraj escaped from prison by drugging a guard and then went to France to kidnap his own daughter. When Compagnon was finally able to escape, she took the child and fled to America to escape Sobhraj’s destructive grip.

Sobhraj, enraged, increased the crime stakes. He held a flamenco dancer hostage in a New Delhi hotel while breaking into a gem shop on the floor below. He rose to prominence as an outlaw in India.

When a young French-Canadian nurse named Marie-Andrée Leclerc met him while travelling in India, she was impressed. “I swore to myself to try all means to make him love me,” she would later write from her prison cell, “but little by little I became his slave.”

He Never Accepted His Killings

Sobhraj was on the run in India in July 1976, wanted for several murders in Thailand and two in Nepal. His first murder was of a taxi driver in Pakistan several years before, but between October 1975 and March 1976, he is suspected of killing 11 more people, nearly all of whom were young backpackers.

He drugged them, led them to believe they had contracted a tropical bug, and prevented them from leaving his apartments on the top floor of Kanit House in Bangkok, often with the assistance of former nurse Leclerc, Anthony writes.

But why he then murdered these innocent young travellers remains a mystery. According to some theorists, he did so because they refused his criminal advances. He was a patriarchal figure who expected submission. “By rejecting Sobhraj’s overtures,” one explained, “they triggered his childhood preoccupation with rejection.”

The man himself was careful not to reveal anything about the situation. He has always maintained the legal position that because he had not been found guilty of any murders, he had not committed any murders. He even denied meeting several of his victims when Andrew Anthony mentioned their names, despite witness statements putting them in his apartment.

“We circled the subject again and again, and it became clear that he was more interested in portraying himself as a victim: of western imperialism, a dysfunctional childhood, racism, and institutionalisation. He’d lapse into philosophical musings one moment, then crack a darkly mordant joke the next. He was narcissistic, amusing, teasing, and, yes, a psychopath,” Anthony writes.

Sobhraj’s alleged crimes in Asia have inspired books and at least one film. Last year, the BBC and Netflix collaborated on a dramatisation of his crimes.

Because of his age, Nepal’s Supreme Court ordered his release. He had completed 19 of his 20-year sentence.

With inputs from Reuters.

Read all the Latest Explainers here

Comments

0 comment