views

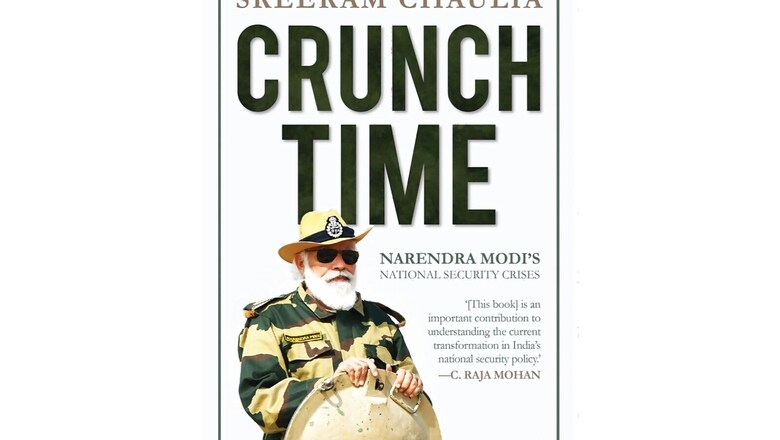

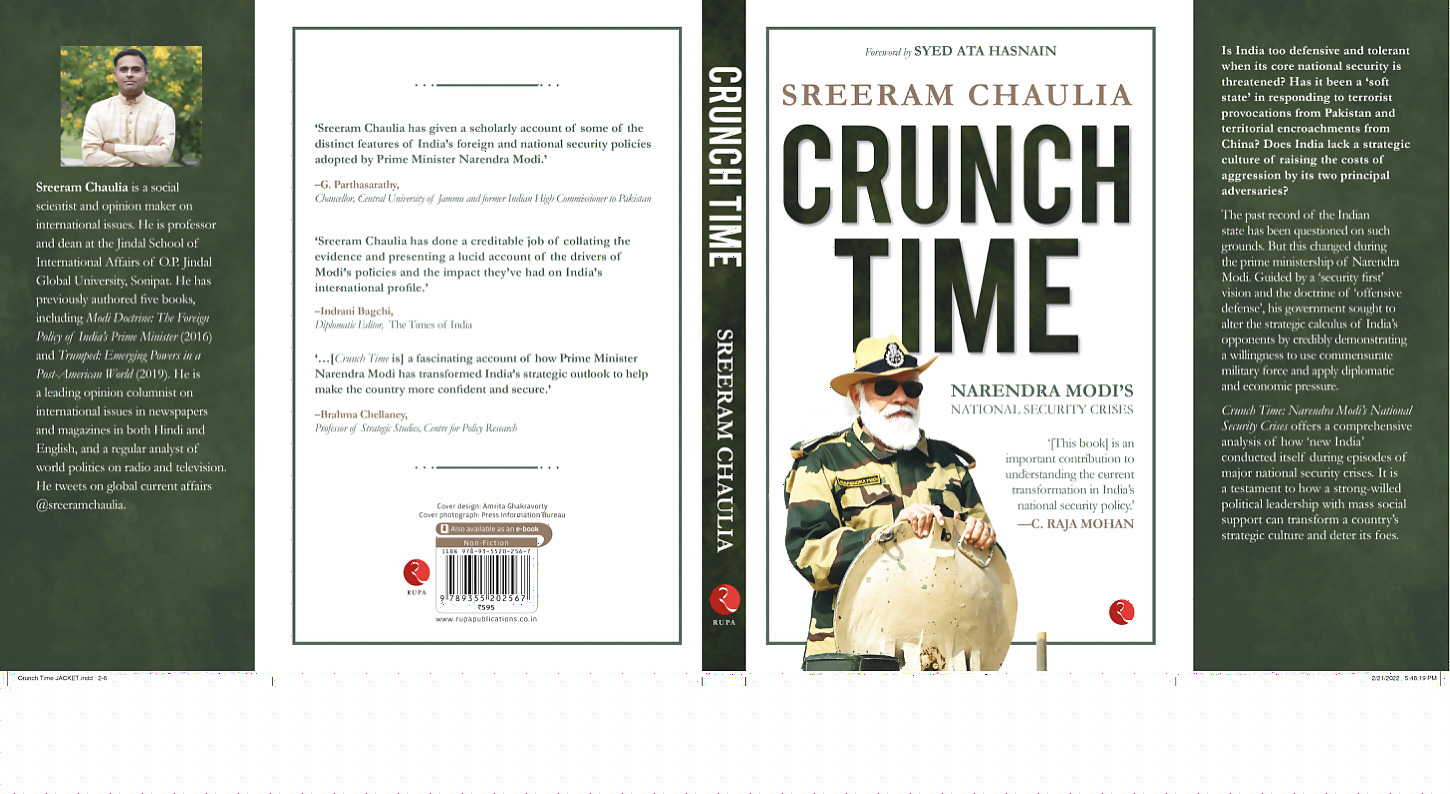

“Crunch Time: Narendra Modi’s National Security Crises” by Sreeram Chaulia, professor of international relations at Jindal Global University is an in-depth and lucid account of India’s national security crises management in recent years.

The book chronicles how ‘New India’ has conducted itself during a series of national security emergencies since Prime Minister Narendra Modi took office in May 2014.

The contrast drawn is with the time India suffered one of its worst terrorist attacks in November 2008 when 10 terrorists of the Pakistan-based Lashkar e Toiba group held India’s financial capital of Mumbai to ransom for almost 60 hours.

“While professing and pursuing a desire for peace with one’s neighbours is a noble sentiment in an ideal world, raison d’ état demands that leaders should bite the bullet and make hard choices during national security crises,” says Chaulia, who holds the position of Dean, at the Sonipat-based university’s Jindal School of International Affairs. The choices India made in the aftermath of the attack – that resulted in no punishment for Pakistan — made the country look like “a soft state” and India emerged “shamefaced” from the episode, Chaulia says. With the Modi government taking office in 2014, there is a paradigm shift in India’s foreign and national security policies including in their alignment. This forms the basis of the differences that can be perceived in the way the Modi government responded to the Uri terrorist strike in 2016 and the Pulwama attack in 2019 as well as China’s attempts to test India’s resolve in Doklam in 2017 and Ladakh in 2020.

There is a clear enunciation of the “Security First vision” and the doctrine of “Offensive Defence.” These two are not mere pronouncements but backed by steely resolve and action, which Chaulia demonstrates in his book that is garnering plaudits for its detailed yet eminently readable look at this transformation in India’s national security policy.

“The baseline from which Modi took over the reins of India had been so devoid of strategic culture and confidence in even limited use of military force that his impact can be accurately characterized as hardening a flabby state that has historically been stubbornly resistant to adaptation or modernization to get in sync with global trends. Not since Indira Gandhi has India had a political leader with the charismatic weight and mass electoral mandate as Modi,” Chaulia writes.

In the chapter dealing with the surgical strikes in the aftermath of the attack on the army camp in Uri, Chaulia recounts Prime Minister Modi’s efforts at peace with Pakistan – his surprise stop-over in Lahore in December 2015 to attend the wedding of then Pakistan Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s granddaughter.

The visit symbolized the prime minister’s belief that relations between countries depend more on “relations between leaders” and less on “full stops and commas on paper, says Chaulia.

In taking the risk to try and walk the path of peace, Modi was well aware of the experience of his predecessor Atal Behari Vajpayee whose goodwill visit to Pakistan in 1999 was soon reciprocated with the Kargil encroachment by the Pakistan military, he says. But the aim was to give peace a chance.

The attack on the Pathankot air force station in early January 2016 weakened Modi’s hand, Chaulia says, given that India’s internal security was seen as weak enough for the terrorists to launch such a daring strike.

The attack on the Uri military camp – seen as the single deadliest attack on the Indian Army in Kashmir in 14 years – brought to an end the attempt by Modi to seek peace with Pakistan. The security crisis that started with the Pathankot attack had “escalated to such a point” that Modi “had to shift gears to greenlight a calibrated use of force to sustain India’s credibility as a capable state,” writes Chaulia. The “surgical strikes” were meant to be “a display of controlled aggression” that showed that India had shed its defensive inhibitions,” he says. It also shattered the idea that India had “no optimal options to respond to Pakistan sponsored terrorism.

While previously, such cross-border raids by the Indian Army were kept shrouded, the Modi government taking political ownership of the surgical strikes was strategic signaling at the highest level – something Pakistan failed to grasp.

In the aftermath of the Pulwama attack in 2019, the Modi government worked hard to diplomatically isolate Pakistan and prevent Islamabad from trying to divert attention from the terrorist attack towards the resolution of the Kashmir dispute or prevention of war.

India’s response also came in the form of an airstrike, 80 kilometers deep inside Pakistan which was a well-thought-out and controlled action. This had the stamp of Modi and National Security Advisor Ajit Doval’s new doctrine of Offensive Defence. It created greater headroom for non-nuclear escalation with New Delhi carefully labelling them as “non-military pre-emptive actions.”

On the challenges posed by China, Chaulia says that Modi in his early meetings with Chinese President Xi Jinping had let the latter know that India would “prioritise national security as the main parameter” in judging bilateral ties. Before Xi’s September 2014 visit, India discovered a Chinese intrusion in Chumar, in eastern Ladakh where it decided to push in more Indian troops to defend Indian territory rather than make any comprises, Chaulia says. When Xi landed in Ahmedabad on the first leg of his India visit, Modi welcomed him on the banks of the Sabarmati river. But that did not mean the informal setting did not afford occasion for some serious talk. Modi is said to have asked Xi when the Chinese troops were moving out of Chumar, Chaulia says. “Modi’s message that ‘even a little toothache can paralyse the entire body,’ was a show of political will and an attempt to set an assertive tone early in the relationship,” Chaulia notes.

The India-China 2017 stand-off at Doklam was however a strong wake-up call for Indian strategic planners to change policy in tackling China.

In his book, Chaulia threads together the complex causes that led to this stand-off. India’s firm response at the military level was backed by deft diplomacy, he says with India surprising China by coming to Bhutan’s help and resolutely standing up for India’s own national security along a third country’s terrain.

“There was a dual message in the show of military resolve – India would proactively defend Bhutan even if it meant an escalation with China particularly if the territorial dispute had direct bearings on India’s own national security,” Chaulia says. It was a “calibrated and well-justified escalation by India without wanting to let the situation get out of control with the involvement of physical violence,” he writes.

A key achievement of the Modi government was that it did not allow any differences to crop up between India and Bhutan despite China’s efforts to create friction through enticements.

Chaulia also refers to Russia coming forward to impress on China the importance of BRICS (Brazil-Russia-India-China-South Africa) solidarity which he says played a role in defusing the situation.

The Chinese intrusions in Ladakh in two years ago should remove any remaining doubts regarding Beijing’s intentions vis a vis India. Caught off guard, it took India a while to come up with a counter when it occupied the Kailash range much to the surprise of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA).

“Xi’s strategy to humiliate India when it was in the throes of the covid-19 crisis did not quite work as he had intended,” writes Chaulia adding that “Modi once again put brakes on Chinese expansionism.”

But he warns that “given the kind of insatiable quest for power that China has acquired under Xi, India is bound to face more crises with it in the future.”

In putting together this book, Professor Chaulia has done creditable work of collating evidence and presenting a very readable and yet also an erudite account of the drivers of Modi’s national security policies. He also refers to higher defence reforms – the creation of an office of the Chief of Defence Staff and going for the theatre commands – that the Modi government has instituted, many years after demands were first raised for institutionalizing them. Taken together, these have gone a long way in transforming India’s strategic outlook to make the country more confident and secure and less of a “soft state.”

“Crunch Time” is almost 300 pages, published by Rupa Publications. It was launched by Minister of State Meenakshi Lekhi on 31 March in New Delhi.

Elizabeth Roche is the former Foreign Editor of Mint. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest Opinion News and Breaking News here

Comments

0 comment