views

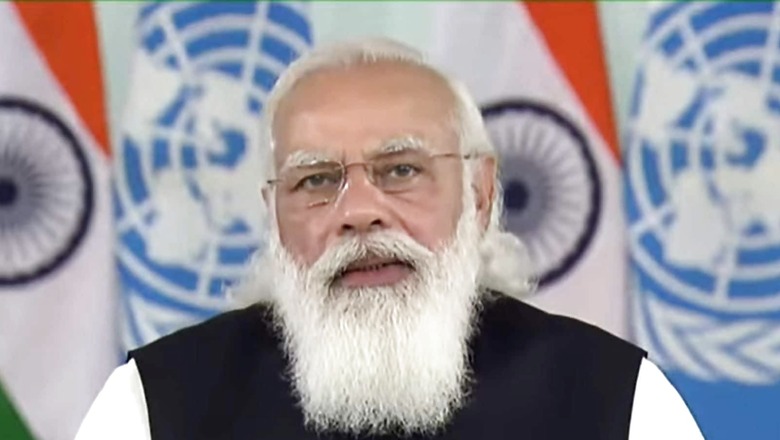

“The ocean is our common heritage … (which) … is facing many challenges,” observed Prime Minister Narendra Modi, emphasising that “sea routes are being misused for piracy and terrorism.” He was kicking off a high-level debate at the UN Security Council, on the vital issue of enhancing maritime security, on August 9. It was for the first time that an Indian Prime Minister was chairing such a session.

Earlier in March 2015, speaking at a handing over ceremony of an India-built 1,350 tonne offshore patrol vessel (OPV) to Mauritius, christened the MCGS Barracuda, PM Modi had remarked, “Terror has visited us from sea”.

The Pakistani terrorists, who perpetrated the ghastly Mumbai attack in November 2008, which could have triggered a war between the two countries, chose the maritime route to enter India. The Indian Navy was in action in two conflicts with Pakistan in 1965 and 1971. The latter made a decisive difference. That India has emerged as the net security provider in the region is to a large extent due to her naval power. And not to forget that peninsular India has a large coastline of over 7,500 km abutting nine states, two Union Territories and two Island territories comprising over 1,200 islands, both inhabited and uninhabited.

Indian cultural traditions spread far and wide through the sea route. Legend has it that in 48 AD, Princess Suriratna from Ayodhya undertook a hazardous two-month sea journey to marry King Kim Suro and become the Queen of Korea. To date, over 95 per cent of India’s trade is seaborne. The European colonisers came by the sea. It is widely believed that future conflicts would be maritime in character. And yes, India is located in one of the most complicated and sensitive geographies. Yet it is a common refrain among the strategic community in India and abroad that she is sea-blind. Really!?

India’s Naval Calculus

In my view, that is unfair and a gross exaggeration. It may be recalled that India was the first Asian country to commission an aircraft carrier INS Vikrant in 1961. Known as HMS Hercules, it was acquired from the British. That said, there is no denying that till a decade or so ago India was ‘sea-complacent’, but not without some reasons. All the conflicts that India has had since Independence with Pakistan and China have essentially been on land. The biggest maritime challenge faced by India was in 1971 when President Nixon ordered USS Enterprise to sail into the Bay of Bengal as a warning.

Hitherto, mostly Pakistan figured in India’s naval calculus. Chinese navy was mostly active in the west Pacific region. Chinese desire for a blue-water navy was known but was deemed a distant horizon. The speed of Chinese naval modernization and expansion was not anticipated by most analysts. Second, Chinese doggedness in acquiring military bases, facilitated by the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), compounded the challenge. And then there has been the perennial resource constraint as well as overcautious politico-bureaucratic approach in finalising defence deals.

Nevertheless, the issue of maritime security has been engaging Prime Minister Modi’s attention from day one. “Collective action and cooperation will best advance peace and security in our maritime region … Our goal is to seek a climate of trust and transparency; respect for international maritime rules and norms by all countries; peaceful resolution of maritime issues … We seek a future for Indian Ocean that lives up to the name of SAGAR – Security and Growth for All in the Region,” he said in March 2015. The approach visualises cooperative measures for sustainable use of the oceans, and a framework for a safe, secure, and stable maritime domain in the region.

Delivering a keynote address at the Shangri La Dialogue on June 1, 2018 he had underlined the imperative – “freedom of navigation, unimpeded commerce and peaceful settlement of disputes in accordance with international law. When we all agree to live by that code … we will be able to prevent maritime crimes, preserve marine ecology, protect against disasters and prosper from blue economy”.

Surprisingly, there is no universally accepted definition of maritime security. At the narrowest it covers freedom of navigation and safety of seafarers; a broader reading will encompass all the facets enumerated above and more. Regardless of the definition, the pre-requisite is collective action and cooperation. No country howsoever powerful can do it alone.

A Veiled Dig at China

Prime Minister Modi’s initiative drew an enthusiastic response. Several heads of state and government, including President Putin of Russia and Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh of Vietnam; the US Secretary of State, French Foreign Minister and the British Defence Minister joined the deliberations. Displaying typical arrogance, the Chinese deputed its deputy permanent representative at the United Nations.

The PM referred to India’s enviable track record and suggested the adoption of a five-point global template to include – removing barriers to maritime trade; peaceful resolution of maritime disputes as per international law; cooperation in addressing maritime threats from non-state actors and natural disasters; conservation of maritime environment and marine resources as well as responsible maritime connectivity.

Modi recognised that necessary infrastructure would have to be built to increase maritime trade. However, (in a veiled dig at China) he cautioned that “fiscal sustainability and absorption capacity of the countries have to be kept in mind in the development of such infrastructure projects”.

Secretary Blinken hailed India’s leadership, especially in championing a free and open Indo-Pacific. He rued that the rules-based maritime order embodied in United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) that had benefited all nations was “under serious threat”. He pointedly referred to “dangerous encounters between vessels at sea and provocative actions to advance unlawful maritime claims” in the South China Sea (SCS). He added that resolving the dispute in the SCS was the “the responsibility of every member-state”.

Expectedly stung, Ambassador Dai Bing averred that the Security Council was not the right place to discuss the issue of the SCS. He accused the US of making “irresponsible remarks and stirring up trouble out of nothing”. He pointed out that the US was not a signatory to UNCLOS and had “no credibility on maritime issues”.

The Security Council adopted a ‘Presidential Statement’ on maritime security reaffirming that “international law, as reflected in the UNCLOS sets out the legal framework applicable to activities in the oceans, including countering illicit activities at sea.” This reiteration was very much required.

While mankind has harvested oceans’ bounties and faced its fury since eternity, the wanton disregard shown by China towards established maritime norms and rule of law has been unprecedented in modern times. Its devious nine-dash line claim on 90 per cent of South China Sea (SCS), use of force, rejection of International Court of Arbitration’s judgement, militarisation of SCS and impediments sought to be imposed on freedom of navigation have set alarm bells ringing in most capitals.

India’s initiative is a wake-up call for everyone to recognise and address the real and imminent threat to our common maritime heritage. If Beijing locates, dusts-off and re-reads the provisions of UNCLOS, it would be a major step forward. Whether it would, remains a million-dollar question.

The author is Former Envoy to South Korea and Canada and Official Spokesperson of the Ministry of External Affairs. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest News, Breaking News and Coronavirus News here.

Comments

0 comment