views

The BJP’s cadre growth and membership numbers have not elicited adequate attention outside party circles. This is because the BJP and the RSS have long had a symbiotic relationship, and the RSS’s cadre network — which has been the focus of relatively more scholarly and journalistic attention — often helps the BJP in elections. However, the party is distinct from the RSS. While Sangh cadres have always been sympathetic to the BJP, they were never the BJP’s own cadres. (A senior RSS leader once famously asked, ‘Which other party is there in the country [for us to support], Sonia Gandhi?’) This means that although the BJP has gained politically from the wider work of RSS workers, it does not control them. It is true that the party has focused on building its own cadres from the day it was born, but its network was not robust enough and widespread enough at the mohalla (street) level in large swathes of India until the early 2000s. So, for decades, it remained deeply dependent on Sangh cadres for voter mobilisation during elections—a situation that had its own pitfalls.

This is why the BJP’s Rajya Sabha MP Swapan Dasgupta rightly argued in 2009 that ‘One of the enduring political myths of India is the belief that, like the Communist Party of India (Marxist), the Bharatiya Janata Party is a cadre-based outfit. This misconception, spread assiduously by both the media and professional saffron watchers in academia who bank on press clippings as primary source material, is centred on the assumption that the Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh is the BJP’s dedicated volunteer army. Consequently, the BJP is expected to replicate the disciplined drill of the RSS. When it fails to do so — and the failures are becoming more and more apparent—the party is judged far more harshly than, say, the Congress whose projected image as a big umbrella party has outlived its degeneration into a dynastic outfit.’ Dasgupta’s deeper point was that the BJP’s party workers, while mostly on the same ideological wavelength, were not as uniformly controlled and the party’s organisational structure was not as efficient as that of the RSS. Moreover, the BJP’s election ground game in many parts of the country was not dissimilar in structure and efficiency (or inefficiency) to that of other political parties.

In the Narendra Modi period, however, the BJP has not only twice secured national electoral majorities, it has followed up these triumphs by vastly expanding its presence in the body politic in a way that few in the Sangh or the BJP would have imagined possible even at the turn of the century.

How the BJP Became Larger Than the Chinese Communist Party and the RSS

Between 2014 and 2020, the BJP created a robust organisational structure of its own at the ground level. In its expansion, it has overtaken the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). This massive expansion of the party base, in fact, replicates many organisational techniques of the RSS. It is important to note that China is a one-party state and Communist Party membership is a prerequisite for career advancement, whereas India is a multi-party democracy. In that sense, the BJP’s accomplishment within a democratic framework has come against greater odds.

BJP leaders often exult about their party being the largest political party in the world. Critics, on the other hand, tended to either not believe the membership numbers or dismissed the party’s organisational growth as inconsequential — as only a vote-gathering machine that somehow comes into play only during election time. Yet, this structural and organisational transformation has been a fundamental enabler of its political power. Not only did district-level expansion help the BJP upend several traditional assumptions of politics in many states, it also fundamentally changed the balance of power between the party and the Sangh.

By 2020, the BJP’s cadre network had dwarfed that of the RSS. It remained tied to the Sangh for ideological reasons, but structurally, it was not quite so dependent on the RSS to mobilise votes. If anything, the RSS was now more dependent on the BJP.

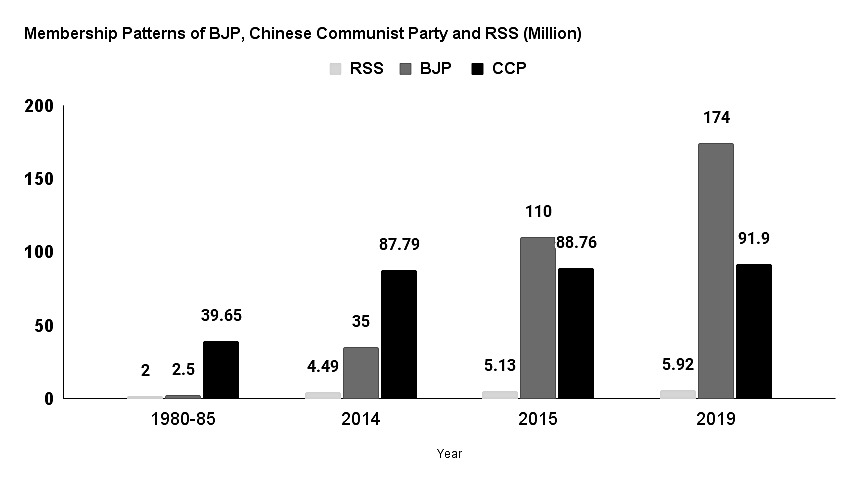

Consider this: in August 2014, when Amit Shah became BJP president, the party claimed to have 35 million members. The CCP, then the world’s largest political party, was over double the size of the BJP at 87.79 million. The maximum RSS daily shakha strength in 2014 — an estimated 4.49 million active members — was about one-seventh of the BJP’s members.

(The RSS does not officially report its primary membership, but annually reports its daily, weekly and monthly shakhas and training camp numbers. For our purposes here, I have made an informed estimate of active RSS members from these reports. First, I discounted the monthly and weekly shakhas — assuming that some people who go to daily shakhas may also be going to the weekly and monthly ones. Then, I used the RSS’s officially reported number of daily shakhas in a year to make three projections: based on whether the average number of attendees at each shakha was fifteen, fifty or one hundred. The calculation gave us an approximate minimum and maximum range for RSS membership numbers. In our comparison of the RSS, the BJP and the CCP, we used the upper range: one hundred attendees on average per RSS shakha. This gave us an estimated maximum of 4.49 million RSS members in 2014.) In other words, to the BJP’s 35 million members in 2014, the RSS had a maximum of 4.49 million.

The BJP tripled in size between 2014 and 2015, the year it surpassed the CCP. Its reported strength of 110 million primary members in 2015 positively dwarfed the CCP’s 88.76 million that year. By then, the party was also roughly twenty times the size of the RSS. By 2019, it had expanded to 174 million signed-up members. This was about twenty-nine times the estimated size of the RSS (see Figure 1).

Put plainly, the BJP grew its membership almost five-fold between 2014 and 2019, during Modi’s first government and under Amit Shah’s presidency. India’s ruling party, in 2019, was claiming membership numbers that were almost twice the size of the CCP.

Figure 1

Source: RSS Annual Reports, CCP Organisation Department, BJP, Multiple Media Sources

This does need to be qualified. The BJP has not only been the party in office at the federal level since 2014, it had held power in as many as seventeen of India’s twenty-eight states by the end of 2019. It is not uncommon for membership numbers of ruling parties to increase for instrumental reasons. Equally, the RSS has often been significant in states where the party has not been in power until recently, such as Maharashtra, where the BJP was in power only in 1995-1999 and 2014-2019, even while it remained home to the RSS headquarters in Nagpur.

Even if we assume that one-third of the members claimed by the BJP in 2019 were ‘transient’ — those attracted to the ruling dispensation and in danger of leaving if the party lost power — the BJP would still be much larger than the CCP (20 per cent) and nineteen times bigger than the RSS.

There is no precedence for this kind of mass-enrolment campaign by a ruling party in independent India. The last time such a party-building exercise was conducted at the national level was when the Congress was built, district by district, during the British Raj. In a similar fashion, the BJP’s expansion of its membership, organisational restructuring and national office building exercise made it the largest political party in the world.

The BJP achieved its growth by seamlessly meshing a major offline restructuring of its internal organisational structures with the adoption of new technologies and digital tools. Leveraging digital technology gave party leaders the ability to organise a large-scale campaign and verify the expansion in a way that simply was not feasible earlier.

ALSO READ | Nalin Mehta Writes: How BJP Won the UP Caste Game and Why Scholars Got it Wrong

The physical restructuring of the party occurred at the lowest rungs: at the voting booth and district levels. It was based on three fundamental pillars: decentralisation and empowerment of local-level functionaries, reservation of key posts for previously under-represented social groups (OBCs, SCs and women) and the creation of new structures of management oversight at multiple levels. For greater management efficiency and accountability, it adopted digital tools on an industrial scale, like the Zoom app for internal meetings, WhatsApp groups for conversations in real time and verifiable telephone-number listings for every single member enrolled in the party.

A mindless embrace of digital tools alone would have been largely useless had it not been backed up by systemic management technique changes. But once the systems were in place, the active use of digital tools that were easily accessed across all generations of devices enabled the BJP to expand its membership with an exactitude that could only have been dreamed of even a decade earlier.

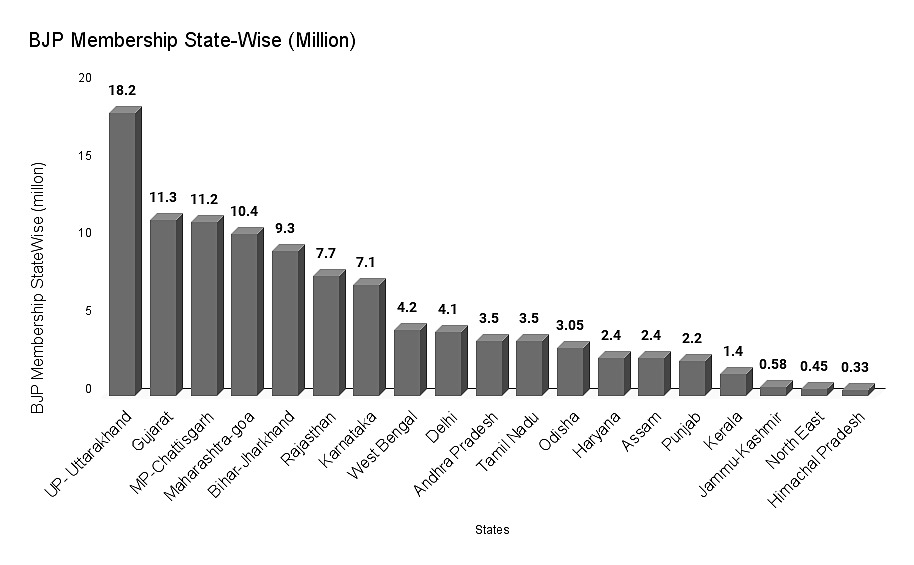

The party’s highest growth came in the states of the Hindi heartland (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: BJP’s Membership Growth Driven by Upsurge in Hindi States, 2015

Source: BJP on Twitter, 30 April 2015: https://twitter.com/BJP4India/status/593728757547962369

This growth was bolstered by the construction of over 500 new party offices in approximately two-thirds of India’s districts. Extraordinarily, these offices were not just created as functional physical spaces replicating the offices of old, but were each equipped with the best digital technology available at the time. Most also contained an archive. If the revamped structure was the fresh lifeblood of the party, the construction of so many more offices sought to build a modern physical foundation for the new BJP under Modi.

Figure 3: BJP’s Office-building Spree: Party Purchased Land in 522 Districts

Amit Shah and UP chief minister Yogi Adityanath holding a havan to simultaneously inaugurate fifty-one district offices of the BJP in UP, 6 February 2019. Source:http://amitshah.co.in/2019-02-06-inaugurated-51-district-bjp-offices-from-bulandshahr-uttar-pradesh/

The BJP’s cadre growth has significant political implications. It is clear that the party believes this massive expansion, among other factors, contributed significantly to its electoral victory in 2019. Amit Shah said as much in May 2019, about a week before the results were declared. Speaking at a joint press interaction with Narendra Modi at the BJP headquarters, he claimed that the party would win a minimum of 300 seats (a claim that proved correct): ‘Look, from 2014 onwards, we have fought a battle for 50 per cent [of seats],’ he said. ‘The way the Narendra Modi government performed, let me give you two statistics. The central government had over 22 crore beneficiaries of its programmes and we got 17 crore votes in the last [2014] election. In the last [2014] election, we had 2.5 crore workers. This time [in 2019] we have 11 crore workers. We are fighting this election as a 50 per cent campaign, and you may not remember, but in states like Himachal Pradesh, Gujarat, Tripura, we crossed 50 per cent.’

This was more than just a four-fold growth of the number of party workers. The manner of enrolment as much as the scale and pace suggested a new process of political mobilisation at work, where party, government records and welfare programmes each reinforced the other.

The spurt in party membership was the outcome of two major year-long enrolment campaigns: in 2014 (1 November) and 2019 (6 July). It must be noted that both campaigns were launched not before but immediately after the party’s election victories. This suggests more long-term aims in party-building and the creation of a system that is more than just a vote-catching machine.

This article is the second part of a three-part special series. You can read the first article in this series here and the third article here.

The author is Dean, School of Modern Media, UPES; Advisor, Global University Systems; and Non-Resident Senior Fellow, Institute of South Asian Studies, National University of Singapore.

Edited extract, with permission, from Nalin Mehta, The New BJP: Modi and the Making of the World’s Largest Political Party, Westland Non-Fiction, 2022.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment