views

The morning of December 16, 1971 at Alwar, Rajasthan was no different from any other day in our lives, until the telephone rang.

My mother Laxmi (25 years old at that time), my brother (seven years) and I (nearly six) were sitting in the living room with the large joint family of my Nana ji (maternal grandfather). Morning prayers had just been said.

The message from the Army over the phone was devastating. My father, Major Hamir Singh, was missing. The war was over and his body had not been found. As per military norms he was, therefore, categorized ‘Missing in Action’.

My mother collapsed and broke into tears. We couldn’t understand what had been said, but seeing our mother cry, my brother and I began crying too.

A few days later, a soldier came home to deliver the personal belongings of my father. The news he shared was even worse.

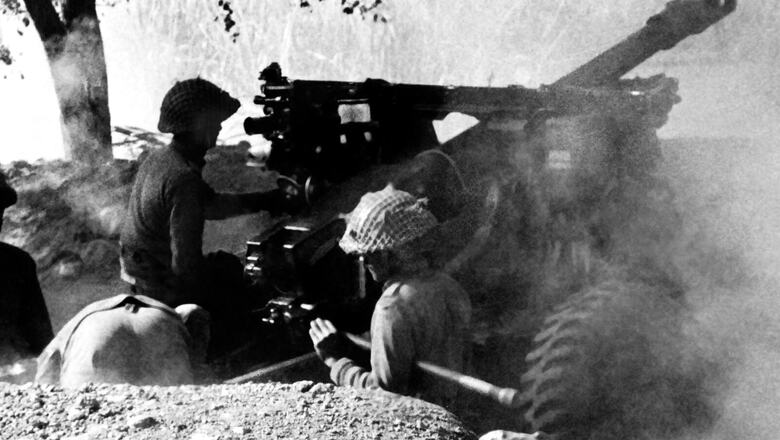

Nothing had been heard about our father since December 14, 1971. His colleagues who had returned from the battle had last seen the grievously injured major involved in a hand-to-hand fight with the Pakistanis. There had been no news about him for almost a month and most in his battalion believed he was dead, like many of his fellow officers and men.

Though the news was terrible, mother refused to believe her husband was no more and she faced life stoically as was expected from a warrior’s wife.

Taking care of two hyperactive children was tough but she was more than up to the task. Concerned as she was about our wellbeing, she successfully insulated my brother and I from her inner turmoil. For us, everything seemed normal.

However, in the loneliness of the night, with her children fast asleep, I can only imagine the demons she may have faced.

Only 25, she was a young, beautiful woman with a tremendous zest for life. To this vivacious, lively mother of two the prospect of spending the rest of her life without her husband would have been truly intimidating.

In those times Rajput widows lived sad and difficult lives. Relegated to the dark corners of their houses, they were considered inauspicious. Dressing up, wearing bright, happy colours or ornaments of any kind was forbidden. They were not expected to join any festivity or celebration and were to grieve for their husbands till the end of their lives.

My mother’s parents and siblings did their very best in keeping her away from negative thoughts. They would keep her engaged in normal activities and take her out to attend social events. But wherever she went she would invariably become the subject of conversation. She would hear hushed comments about her misfortune. But the brave lady would never break down in front of her children, parents or relatives. Instead, she would resign herself to silent tears until late at night.

The uncertainty over her husband remained for almost 45 days, until early February ’72 when she received the most wonderful news through a postcard from her husband. He had written from a hospital in Pakistan, where he was now a Prisoner of War (PoW).

Though delighted, what worried her now was the extent of his injuries and whether he would ever be repatriated. It was a well-known fact that not all PoWs of previous wars had returned.

The uncertainty of those few months affected my mother adversely. She lost part of her gregarious nature and turned somewhat circumspect. From a jovial, light-hearted person she took to religion and to date spends many hours in prayer. Asthma and related ailments have got the better of an otherwise healthy, robust woman.

Barely six years old when the war commenced, I have very few memories of this difficult period. We had just returned to India after spending almost three years in Nigeria, where my father had been an instructor at the Nigerian Defence Academy. I had spoken my first words in Nigeria and since our teachers in school were British, the only language I spoke or understood was English. The first casualty of our father’s absence was, therefore, our education.

Being a police officer Nana ji was posted in small towns in Rajasthan such as Dholpur and Jaisalmer, where education was rudimentary. From an excellent introduction to schooling in a British-run school in Nigeria we were thrust into schools where we couldn’t understand a word of what the teachers taught. Our British accent stood out starkly amongst the children, making us the butt of jokes and ridicule.

My brother was nearly eight at that time and my father’s absence affected him more than me. He missed our father and would sometimes have nightmares at night to my mother’s concern.

My paternal grandfather, Major General Kalyan Singh, who had just retired from service was an equally worried father. During the Second World War, he had been captured by the Germans in North Africa while fighting against Rommel’s Army. Having spent considerable time in an Italian PoW camp, he had experienced how tough survival could be. Besides, helping his young daughter-in-law cope with the situation and raise her two young children was a matter of his immediate concern. A veteran, who had participated in many wars, he had never imagined he would have to fight yet another battle after he retired.

ALSO READ | Swarnim Vijay Diwas: The Officers Who Won India a Decisive Victory against Pakistan in 1971

My father was repatriated to India on December 1, 1972. In my opinion, he is the person most affected from his experience. Mostly calm, he seldom loses his temper but on rare occasions that he does, the trigger is hard to predict. On such occasions he is an entirely different person, shaking and trembling in anger.

Thankfully, such occasions are rare. We believe that over the last 50 years he has healed somewhat. Having earned a Vir Chakra, he is now a legend in the Grenadiers Regiment.

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is rarely spoken of in India. Having read about it later in life, I now realize that my father has silently suffered PTSD since December 1971.

Today, both my brother and I are serving Generals, living happy, fulfilling lives. My son is poised to become the fifth generation of our family in the Army. That we have come through such a terrible experience unscathed, the credit entirely goes of our parents.

It’s been 50 years and as they say ‘all’s well that ends well!’ But we know, for our parents this is true, but only on the surface.

What our parents have endured we will never forget till the day we die.

Major General Vijay Singh is the author of POW 1971: A Soldier’s Account of the Heroic Battle of Daruchhian published by Speaking Tiger Books, 2021. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment