views

They made quite a team. One was an Oxford-educated wunderkind who handled the complicated math behind the transactions. The other was a beefy, 6-foot-2 New Zealander with an apparent fondness for Hawaiian shirts, who brought in clients and money.

Martin Shields and Paul Mora met in 2004, at the London office of Merrill Lynch. Shields was always the pupil, a little in awe of the older man’s ability to bluff and charm. Once, after Mora fended off suspicious auditors at a bank where the two worked, Shields sent an admiring email.

“Remind me never to play poker with you,” he said, according to an internal report later commissioned by the bank.

Today, the men stand accused of participating in what Le Monde has called “the robbery of the century,” and what one academic declared “the biggest tax theft in the history of Europe.”

From 2006 to 2011, these two and hundreds of bankers, lawyers and investors made off with a staggering $60 billion, all of it siphoned from the state coffers of European countries. As one participant would later put it, taxpayer funds were an irresistible mark for a simple reason: They never ran out.

The scheme was built around “cum-ex trading” (from the Latin for “with-without”): a monetary manoeuvre to avoid double taxation of investment profits that plays out like high finance’s answer to a David Copperfield stage illusion. Through careful timing, and the coordination of a dozen different transactions, cum-ex trades produced two refunds for dividend tax paid on one basket of stocks.

One basket of stocks. Abracadabra. Two refunds.

The process was repeated over and over, as word of cum-ex spread like a quiet contagion. Germany was hardest hit, with an estimated $30 billion in losses, followed by France, taken for about $17 billion. Smaller sums were drained away from Spain, Italy, Belgium, Austria, Norway, Finland, Poland and others.

Outrage in these countries has focused on the City of London, Britain’s answer to Wall Street. Less scrutinized has been the role played by Americans, both individual investors and branches of U.S. investment banks in London, including Morgan Stanley, JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

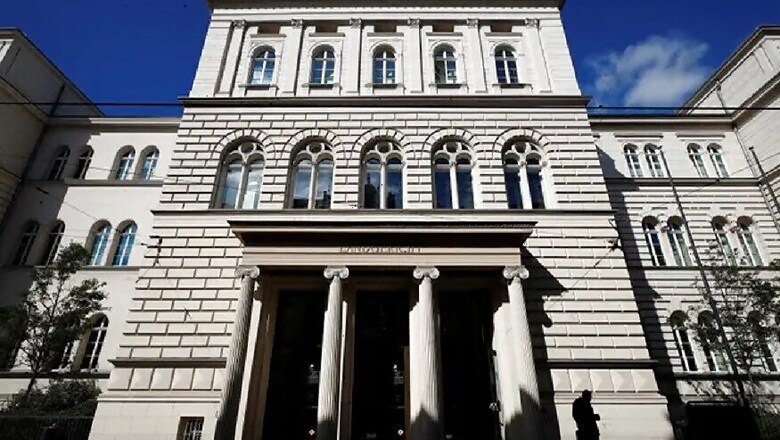

Exactly how the scheme operated is a central question in the first cum-ex prosecution, which began in September in Bonn, Germany.

In a trial expected to last until February, German prosecutors intend to make an example of Shields, 41, and a former colleague. (Mora, 52, was indicted in December and will be tried separately in the coming months.) The men in the Bonn case have been charged with “aggravated tax evasion” that cost the German treasury close to $500 million.

Last month, the presiding judge issued a preliminary ruling that, for the first time, declared cum-ex a felony, calling it a “collective grab in the treasury.” Punishment has yet to be determined, but the give-it-back and the go-to-prison phases of this calamity are about to begin.

German prosecutors say they will pursue 400 other suspects, unearthed in 56 investigations. Banks large and small will be ordered to hand over cum-ex profits, which could have serious consequences for some. Two have already gone bust.

Dozens of law firms and lawyers may face penalties, too, having drafted highly priced opinions contending there was no law explicitly prohibiting cum-ex and thus it was perfectly legal. That is an argument that many involved might offer in the coming years of litigation. They may insist that if Germany didn’t make the trade impossible, they did not break a law. A desk-thumping variation of that defense is already being offered by Hanno Berger, once the most formidable tax auditor in Germany, who later switched sides and became a cum-ex mastermind as well as an ally of Shields and Mora.

Unidentified Flying Stocks

American investment banks and hedge funds have long been the leading laboratory for financial instruments, some a boon to economies (money market funds), others not (collateralized debt obligations). Precisely who invented cum-ex trading, and when, are mysteries, but ground zero for this scandal may have been the London branch of Merrill Lynch.

That is where Shields took his first job in 2002. He has yet to enter a plea — that comes later in the German system — but he has been cooperating with prosecutors in the hope of winning leniency, and he read a long statement at the start of proceedings in September to the panel of judges who will decide the case.

Sitting at a table beside a translator, he said he regretted ever entering the cum-ex world. Back then, though, he had “different information and a different perspective.”

That perspective came largely from Mora, his onetime boss at Merrill Lynch, an obese man fond of wearing loud shirts and Bermuda shorts in London, according to a description in Die Zeit, a German newspaper. A New Zealand publication, Stuff, wrote in October that Mora now lives in a luxurious house overlooking a golf course in Christchurch and owns a portfolio of properties, including an interest in dairy farms.

Through his lawyers, Mora has denied wrongdoing. He has also denied having an eccentric taste in clothing. In 2017, he issued a statement to Stuff ridiculing Die Zeit’s account of his appearance.

“That’s so far from the truth it’s laughable,” he wrote.

At Merrill, Shields’ job was to identify “tax-attractive trades,” as he put it in his testimony. He had joined one of the least visible sectors of the financial world, which pokes at the seams of international finance law, looking for ways to reduce clients’ tax bills.

Many of these were variations of a strategy called “dividend arbitrage,” and right before Shields left Merrill in 2004, he learned about a new one, cum-ex, that would soon become the focus of his life.

Academics have struggled for years to explain the trade and say its impenetrability is part of what made it so successful — as though someone had found a way to weaponize string theory. At the Bonn trial, defendants spent days walking judges through cum-ex’s nuances, with one baffling slide after another.

Suffice it to say, the goal was to fool the financial system so that two investors could claim refunds for dividend taxes that were paid just once.

Some of the best legal minds in Europe spent much of their working hours writing opinions declaring cum-ex within the bounds of the law. One of those lawyers was Hanno Berger, now 69, who provided Shields and Mora with an invaluable legal imprimatur, as well as a kind of remorseless zeal.

A lawyer who worked at the firm Berger founded in 2010, and who under German law can’t be identified by the media, described for the Bonn court a memorable meeting at the office.

Sensitive types, Berger told his underlings that day, should find other jobs.

“Whoever has a problem with the fact that because of our work there are fewer kindergartens being built,” Berger reportedly said, “here’s the door.”

To German prosecutors, Berger is an archetype straight out of a potboiler: the revered enforcer who went to the dark side. In 2012, the government raided his home and law firm. Within hours, he drove to Switzerland, where he now lives.

He will stand trial in the same case as Mora, for aggravated tax evasion. Reached by email, Berger said he remained convinced that cum-ex trading is legal.

“The current prosecution in the context of cum-ex is the attempt of the German tax administration to obscure the failure of the politicians and the legislation in a retroactive way,” he wrote. “This is not appropriate for a state of law!”

‘A Lot of Nonsense’

Berger began working with Shields and Mora after the two left Merrill Lynch for the London branch of HypoVereinsbank, a bank based in Munich. By 2006, Mora’s group was producing immense profits and plenty of internal suspicion. Worried about the growing pileup of tax-withholding credits on the books, Frank Tibo, the bank’s chief tax officer, flew to London in May 2007. He spent the day grilling Mora in a company conference room, Tibo recalled in a recent interview.

“He just told me a lot of nonsense,” Tibo said. “He said he had this toolbox of financial instruments and he’s in the middle of these trades, and that sometimes he doesn’t even know who he is trading with.”

When Tibo tried to signal his concern to executives at UniCredit, the bank’s Italian owner, they didn’t seem to care, he said.

With the financial crisis in full swing, cum-ex was one of the few reliable moneymakers, and the trade boosted careers throughout the City of London. Prosecutors have reportedly opened investigations into transactions handled by Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, Morgan Stanley and many others. Dozens of German banks participated in cum-ex deals, too, gobbling up German taxpayer money at the same time they received a rescue package worth more than $500 billion.

Spokesmen for JPMorgan Chase, Morgan Stanley and Bank of America, which took over Merrill Lynch in 2008, said they had no comment.

Suspicious Snapchats

Two weeks ago a former Merrill Lynch investment banker sat in a London restaurant near the Thames and described what had turned him into a whistleblower. In the years after the financial crisis, he said, he noticed that a handful of colleagues on the company’s trading floor were using their personal mobile phones, a breach of company policy. All communication was supposed to be tracked and recorded. These guys were sending self-deleting texts on Snapchat.

“Obviously, they were circumventing controls,” he said.

When he pointed this out to management, the policy was tweaked.

“They said, ‘You can answer a call on your mobile, but you need to immediately move off the floor,’” he recalled. “So these guys would get up from their desks, start walking toward the edge of the floor, send a text message and then walk back. It was a joke.”

The whistleblower requested anonymity for this article because he was discussing confidential information. Nearly all of it was included in a long complaint he sent in 2012 to the Office of the Whistleblower at the Securities and Exchange Commission in Washington.

A copy of the complaint was obtained by a team of reporters from Die Zeit, the news website Zeit Online and “Panorama,” which spent four years studying the cum-ex business. The team shared the document with The New York Times.

The complaint lays out, in painstaking detail, how the trades were confected, who executed them and which questions should be asked by investigators to uncover the “sham.” It states that Merrill Lynch earned hundreds of millions of dollars over the previous seven years from cum-ex trades.

A spokeswoman from the SEC declined to comment.

American banks conducted their cum-ex trades overseas, rather than at home, out of fear, the whistleblower said. Specifically, he mentioned a 2008 Senate investigation into “dividend tax abuse” that found it was depriving the Treasury of $100 billion every year. The report led to a ban on dividend arbitrage tied to stock in U.S. corporations.

But nothing prevented American bankers from conducting such trades with foreign companies on foreign soil.

Eventually, American investors joined in, too. German efforts to stamp out cum-ex with legislation, in 2007 and 2009, left holes through which certain types of financial players could still crawl. This included private pension plans in the United States, a niche financial product for wealthy people who want the kind of privacy, and exotic investment options, that Fidelity doesn’t offer.

“These U.S. pension plans became the holy grail for cum-ex trading,” said Niels Fastrup, a co-author with Thomas Svaneborg of “The Great Tax Robbery.” “They were perceived by tax authorities as very trustworthy, and all European countries had agreements with the U.S., so these plans could claim 100% of withheld taxes.”

But in 2011, a clerk in the Bonn Federal Central Tax Office, who was interviewed by the German media team and has remained anonymous, came across tax refund applications that looked dubious. They were from a single American pension fund that had bought, then quickly sold, $7 billion in German stock. Now it wanted a tax refund of $60 million. The fund had just one beneficiary.

Instead of paying the refund, the clerk made inquiries. She soon received a peppery letter from a German law firm that threatened to hold her “PERSONALLY” accountable “under criminal, disciplinary and liability law.” The clerk reported all of this to prosecutors, which ultimately led to the trial in Bonn.

Last year, a crew from “Panorama” tracked down the fund’s beneficiary, Gregory Summers, who lives in a grand home in Green Brook, New Jersey. A reporter tried to interview Summers in his driveway as he sat in the passenger seat of a black Mercedes-Benz.

“I can’t talk to you,” he said, and the Mercedes drove away.

Messages left with Summers’ family were not returned.

Cum-Exit

The cum-ex reckoning has already begun. Several banks have been fined (Deutsche Bank, UniCredit), one has apologized (Macquarie), others have pledged cooperation with investigators (Santander, Deutsche Bank) and two are insolvent. A lawyer from Freshfields, a prestigious London firm that provided cum-ex advice, was briefly jailed by the German authorities in late November and has reportedly been charged with fraud.

If the Bonn trial ends in convictions, stiff penalties are expected.

“They won’t even have to prove that the banks were complicit or that the banks were trying to evade taxes,” said Dierk Brandenburg of Scope, a credit-rating agency in London. “The fact that they benefited means they have to give the money back.”

Investors will have problems of their own. Many have said they had no idea how cum-ex traders returned such dazzling profits. That defense became less plausible in 2012, after the German government spent millions of dollars to buy 11 hard drives from industry insiders. The hard drives were filled with marketing flyers, written by bankers, who sold cum-ex with an antigovernment pitch.

“We learned that it was very common for these bankers to have conversations over coffee with clients about cum-ex,” said Norbert Walter-Borjans, a former minister of finance for North Rhine-Westphalia. “They would say, ‘If you have a problem with how your hard-earned money is being spent in taxes, we’ve got an idea for you.’”

David Segal c.2020 The New York Times Company

Comments

0 comment