views

Isolating a Chicken to Examine and Clean Wounds

Watch closely for signs of pecking injuries. Observe your flock at least 2-3 times per day for pecking activities that go beyond the typical gentle pecking. Whether you observe aggressive pecking or not, assume a pecking injury if you see broken or missing feathers on a bird, especially if accompanied by bleeding or bruising. Don’t confuse pecking injuries for moulting. When a chicken is moulting its feathers will be crooked, not broken or damaged. Mild pecking is a normal behavior related to the hierarchy—the “pecking order”—that develops in a flock. Severe pecking is an abnormal but not uncommon behavior among chickens.

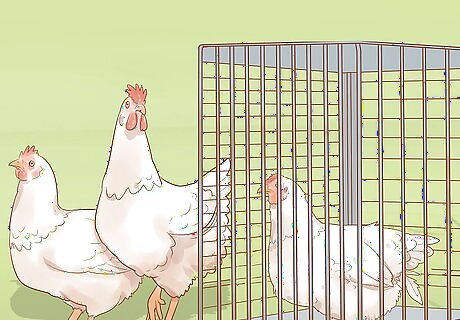

Remove the injured chicken from the flock immediately. Immediate isolation of the injured bird is important for 3 reasons. First, it greatly improves the chances of the chicken’s recovery. Second, severe pecking is a learned behavior that can spread rapidly through a flock. Third, bleeding injuries are magnets for pecking that can turn into cannibalism, which is also a learned behavior within a flock. If you can identify a particular bird that is doing the severe pecking, remove it from the flock and keep it in isolation while the injured bird heals (in separate isolation). You can try reintegrating both back into the flock (first the injured bird, then the attacking bird) once the pecked chicken heals.

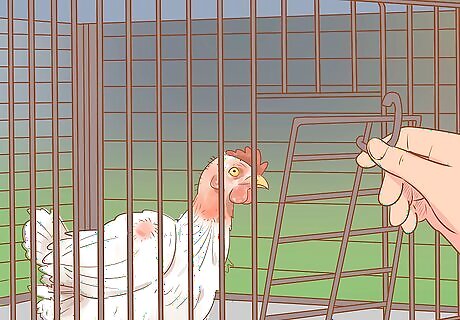

Set up a properly supplied isolation cage for the injured bird. The isolation cage should be set up like a smaller version of the primary enclosure. Make sure it has proper bedding, a food dish, a water bottle, enrichment materials (that is, things for the bird to peck at), and so on. The isolation cage should be at least 3 × 2 × 2 ft (91 × 61 × 61 cm) in size. A medium or large dog kennel cage makes a good “chicken hospital” for isolation and treatment. If you're also isolating an attacking bird, set up a similar isolation cage in a separate location.

Put on gloves and stop the bleeding with a clean cloth. Once you’ve isolated the injured bird, put on vinyl gloves and hold a clean cloth to the wound until any active bleeding stops. Hold the chicken securely in your arms while trying to keep it as calm as possible. Dish gloves are a great option for protecting your hands while you handle the chicken. If the wound isn’t actively bleeding, skip this step (but put gloves on regardless).

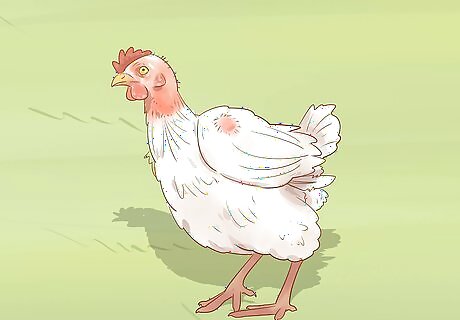

Rinse the area with water and examine the wound. While maintaining a secure hold on the bird, pour clean, tepid water over the wound to rinse away any dried blood and debris. Push any feathers out of the way to get a good look at the wound. If the wound is primarily red and bruised, with some bleeding spots, you can probably nurse the chicken back to health yourself.

Seek the help of a poultry vet for severe and/or internal injuries. If the bleeding won’t stop, the wound covers a large area, or the pecking has penetrated deep into the flesh, you probably can’t heal the chicken yourself. Call a veterinarian who specializes in poultry. It can, however, be difficult to find a vet that will care for injured chickens. They may be willing to euthanize the chicken for you, or you can decide if you’re willing and able to euthanize the chicken yourself in a humane manner.

Healing the Wounds and Reintegrating the Bird

Apply wound spray during continued isolation for the best results. After you’ve rinsed out and inspected the wound, apply a poultry wound care spray to the injured area. Use the spray 3 times per day, or as instructed on the package, until the injury has healed. You can find poultry wound spray at agricultural supply stores. The chicken needs to remain isolated until the wound heals, or the pecking will most likely resume.

Apply a concealing wound spray to reintegrate a healing bird. If you need or want to return the bird to the flock while it heals, use a wound spray that comes pre-dyed—they’re usually blue or purple in color. The dye conceals the wound so that other chickens aren’t encouraged to peck at it. The sight of a wound, especially a bleeding one, encourages the other chickens to keep pecking at it. It may also encourage fighting or other aggressive behavior. The dyed spray conceals the blood and wound. Follow the package instructions for using the product. You can find wound concealing spray at agricultural supply stores as well. This is a less effective option than keeping the bird isolated during treatment.

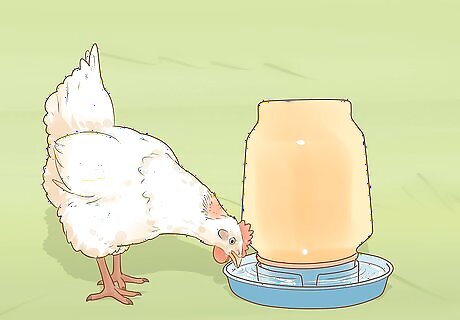

Offer lots of water supplemented by electrolytes. During the injured chicken’s healing process, be extra vigilant to ensure that it always has an ample supply of fresh water. To further promote healing, add an electrolyte supplement to its water supply as well. You don’t need to give the bird more food than normal, and don’t be concerned if it eats less than usual for a few days. But make sure it stays hydrated. You can buy electrolyte additives at pet suppliers or feed stores. Some come in powder form, while others are drops. For instance, the package might instruct you to add a 0.25 oz (7.1 g) packet of powder to 1 US gal (3.8 L) of water daily for up to 5 days.

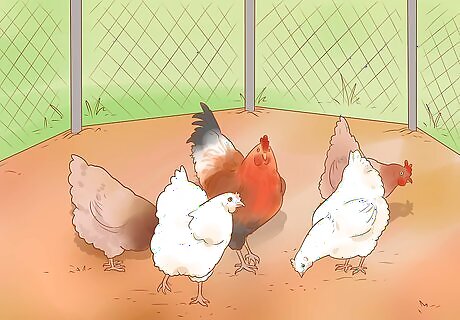

Reintegrate the bird slowly and check on it at least 5 times daily. When the injured bird has healed, slowly reintegrate it into the flock, almost as if it is a new bird. You may, for instance, move its temporary cage right beside the main enclosure for a few days before releasing the bird into the flock. Once it has rejoined the flock, keep a close eye on the bird for signs of pecking injuries. If the bird is being pecked aggressively again, you may need to remove it permanently. If you’ve isolated a bird that was pecking aggressively, slowly reintegrate it and monitor it in the same fashion. If it starts pecking aggressively again, remove it permanently.

Reducing the Likelihood of Severe Pecking

Choose birds that have been bred for reduced pecking behavior. While aggressive pecking—sometimes leading to cannibalism—is largely a learned behavior within a flock, there is a hereditary component as well. Pecking behavior can be reduced through selective breeding, so ask any chicken breeders you use about pecking behavior among their breeding stock. Pecking cannot be bred out entirely—it’s an innate behavior among chickens. And even birds that are bred to be less pecking-prone can become aggressive peckers or even cannibals under poorly-maintained conditions.

Provide adequate spacing for your chickens in their enclosure. Not surprisingly, if chickens are too crowded together and are jostling for space, they’re more likely to peck at each other. Generally speaking, the more room to roam that you can give your birds, the less likely they’ll be to engage in aggressive pecking. Provide at least 5 sq ft (0.46 m) of ground space per bird. This isn’t a cure-all, however. Even free range chickens can engage in aggressive pecking behavior.

Maintain comfortable temperatures and lighting in the enclosure. If the temperature within the coop dips below 70 °F (21 °C) or rises above 95 °F (35 °C), the chickens’ discomfort may encourage aggressive pecking. Likewise, the chickens will become agitated and more prone to pecking it they are subjected to more than 16 hours of light per day. Provide a suitable heating source for the coop if necessary in cooler weather, or add ventilation if the coop gets too hot during the summer. If you’re using artificial light, employ a timer to limit when the light is on—12-16 hours of light per day (including daylight) is ideal to encourage egg production.

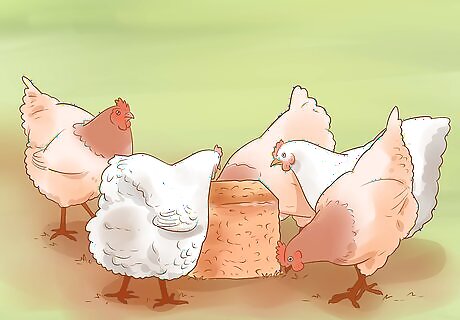

Ensure adequate nutrition and encourage foraging behavior. Provide a high-quality chicken feed that is nutritionally balanced. Additionally, scatter up to an additional 1 tsp (5 g) of feed per chicken in the enclosure and cover it with straw, grass clippings, or leafy greens. Foraging for food will keep the chickens occupied and allow them to engage in safe pecking behavior. Chickens that lack key nutrients or that are underfed may resort to cannibalistic pecking in search of adequate nutrition.

Offer lots of enrichment materials to keep the birds occupied. If you give chickens other things to peck at and play with, they’re less likely to peck at each other. Try adding several of the following to the enclosure: Pecking blocks, which you can get at feed stores. Simply scatter them throughout the coop. Pieces of your (live) Christmas tree after the season ends. Cut the tree into 3 or more sections and place them in the coop. Old soccer balls or footballs. They can be fully or partially inflated. Lengths of rope or polypropylene twine. Tie 8-10 of them to the ceiling of the coop so that they hang down to about 6 in (15 cm) off the ground. CDs or half-filled plastic water bottles. Tie them to the end of the twine you strung down from the coop ceiling.

Maintain a flock size of less than or more than 30 birds. Anecdotal evidence indicates that flocks of around 30 birds are most likely to result in aggressive pecking. With flocks smaller than this, the birds are more able to establish a stable social hierarchy (“pecking order”) in which each bird recognizes all the others. On the other side of the coin, the sheer size of larger flocks weakens the hierarchy altogether and reduces the urge to peck as a means of social control.

Comments

0 comment