views

Researching Your Topic

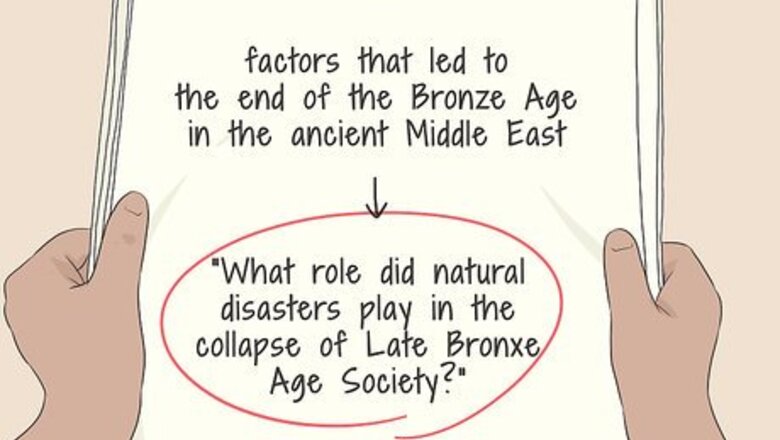

Focus your research on a narrow topic. As you conduct research, try to make your paper’s subject more and more narrow. You can’t defend an argument about a super broad subject. However, the more refined your topic, the easier it’ll be to pose a clear argument and defend it with well-researched evidence. It’s easy to drift off course, especially in the early research stages. If you feel like you’re going off-topic, reread the prompt to help get yourself back on track. Tip: If you need to analyze a piece of literature, your task is to pull the work apart into literary elements and explain how the author uses those parts to make their point. For instance, you might start with a general subject, like British decorative arts. Then, as you read, you home in on transferware and pottery. Ultimately, you focus on 1 potter in the 1780s who invented a way to mass-produce patterned tableware.

Search for credible sources online and at a library. If you’re writing a paper for a class, start by checking your syllabus and textbook’s references. Look for books, articles, and other scholarly works related to your paper’s topic. Then, like following a trail of clues, check those works’ references for additional relevant sources. Authoritative, credible sources include scholarly articles (especially those other authors reference), government websites, scientific studies, and reputable news bureaus. Additionally, check your sources' dates, and make sure the information you gather is up to date. Evaluate how other scholars have approached your topic. Identify authoritative sources or works that are accepted as the most important accounts of the subject matter. Additionally, look for debates among scholars, and ask yourself who presents the strongest evidence for their case. You’ll most likely need to include a bibliography or works cited page, so keep your sources organized. List your sources, format them according to your assigned style guide (such as MLA or Chicago), and write 2 or 3 summary sentences below each one.

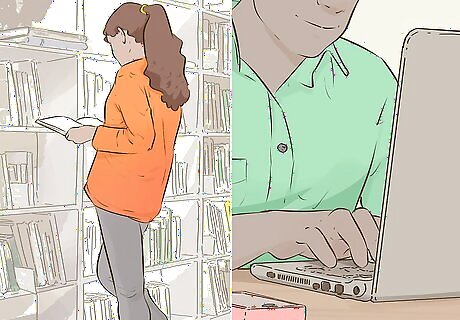

Come up with a preliminary thesis. As you learn more about your topic, develop a working thesis, or a concise statement that presents an argument. A thesis isn’t just a fact or opinion; rather, it’s a specific, defensible claim. While you may tweak it during the writing process, your thesis is the foundation of your entire paper’s structure. Imagine you’re a lawyer in a trial and are presenting a case to a jury. Think of your readers as the jurors; your opening statement is your thesis and you’ll present evidence to the jury to make your case. A thesis should be specific rather than vague, such as: “Josiah Spode’s improved formula for bone china enabled the mass production of transfer-printed wares, which expanded the global market for British pottery.”

Drafting Your Essay

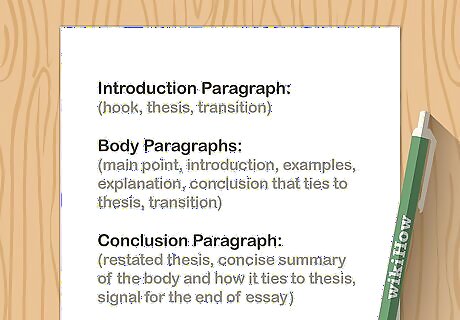

Create an outline to map out your paper’s structure. Use Roman numerals (I., II., III., and so on) and letters or bullet points to organize your outline. Start with your introduction, write out your thesis, and jot down your key pieces of evidence that you’ll use to defend your argument. Then sketch out the body paragraphs and conclusion. Your outline is your paper’s skeleton. After making the outline, all you’ll need to do is fill in the details. For easy reference, include your sources where they fit into your outline, like this:III. Spode vs. Wedgewood on Mass ProductionA. Spode: Perfected chemical formula with aims for fast production and distribution (Travis, 2002, 43)B. Wedgewood: Courted high-priced luxury market; lower emphasis on mass production (Himmelweit, 2001, 71)C. Therefore: Wedgewood, unlike Spode, delayed the expansion of the pottery market.

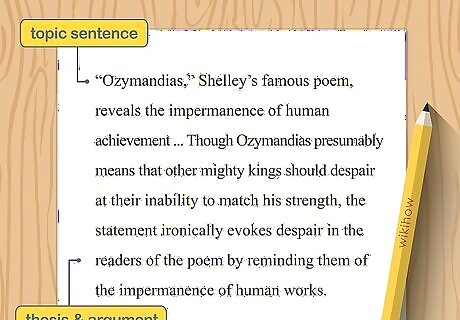

Present your thesis and argument in the introduction. Start with an attention-grabbing sentence to draw in your audience and introduce the topic. Then present your thesis to let them know what you’ll be arguing. For the remainder of the introduction, map out the evidence you’ll use to make your case. For instance, your opening line could be, “Overlooked in the present, manufacturers of British pottery in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries played crucial roles in England’s Industrial Revolution.” After presenting your thesis, lay out your evidence, like this: “An examination of Spode’s innovative production and distribution techniques will demonstrate the importance of his contributions to the industry and Industrial Revolution at large.”Tip: Some people prefer to write the introduction first and use it to structure the rest of the paper. However, others like to write the body, then fill in the introduction. Do whichever seems natural to you. If you write the intro first, keep in mind you can tweak it later to reflect your finished paper’s layout.

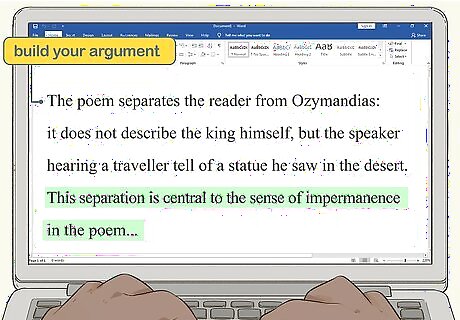

Build your argument in the body paragraphs. First, set the context for your readers, especially if the topic is obscure. Then, in around 3 to 5 body paragraphs, focus on a specific element or piece of evidence that supports your thesis. Each idea should flow to the next so the reader can easily follow your logic. For a paper on British pottery in the Industrial Revolution, for instance, you'd first explain what the products are, how they’re made, and what the market was like at the time. After setting the context, you'd include a section on Josiah Spode’s company and what he did to make pottery easier to manufacture and distribute. Next, discuss how targeting middle class consumers increased demand and expanded the pottery industry globally. Then, you could explain how Spode differed from competitors like Wedgewood, who continued to court aristocratic consumers instead of expanding the market to the middle class. The right number of sections or paragraphs depends on your assignment. In general, shoot for 3 to 5, but check your prompt for your assigned length.

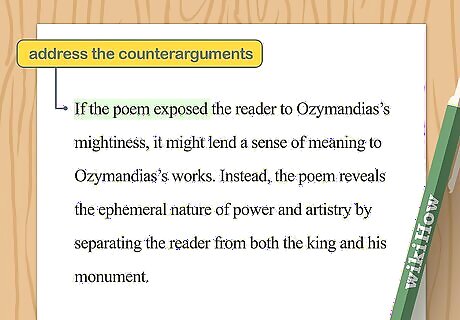

Address a counterargument to strengthen your case. While it’s not always necessary, addressing a counterargument can help make your argument more convincing. After layout out your evidence, mention a contrasting view on the topic. Then explain why that differing perspective is incorrect and why your claim is more plausible. If you bring up a counterargument, make sure it’s a strong claim that’s worth entertaining instead of ones that's weak and easily dismissed. Suppose, for instance, you’re arguing for the benefits of adding fluoride to toothpaste and city water. You could bring up a study that suggested fluoride produced harmful health effects, then explain how its testing methods were flawed.

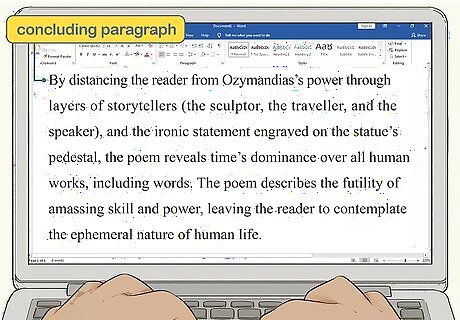

Summarize your argument in the conclusion. Think of your paper’s structure as “Tell them what you’ll tell them. Tell them. Tell them what you told them.” After the paper’s body, remind the reader of your thesis and the steps you’ve taken to defend it. Sum up your argument, but don’t simply rewrite your introduction using slightly different wording. To make your conclusion more memorable, you could also connect your thesis to a broader topic or theme to make it more relatable to your reader. For example, if you’ve discussed the role of nationalism in World War I, you could conclude by mentioning nationalism’s reemergence in contemporary foreign affairs.

Revising Your Paper

Ensure your paper is well-organized and includes transitions. After finishing your first draft, give it a read and look for big-picture organizational issues. Make sure each sentence and paragraph flow well to the next. You may have to rewrite a paragraph or swap sections around, but taking the time for revisions is important if you want to hand in your best work. This is also a great opportunity to make sure your paper fulfills the parameters of the assignment and answers the prompt! It’s a good idea to put your essay aside for a few hours (or overnight, if you have time). That way, you can start editing it with fresh eyes.Tip: Try to give yourself at least 2 or 3 days to revise your paper. It may be tempting to simply give your paper a quick read and use the spell-checker to make edits. However, revising your paper properly is more in-depth.

Cut out unnecessary words and other fluff. In addition to your paper’s big-picture organization, zoom in on specific words and make sure your language is strong. Double check that you’ve used the active voice instead of the passive voice, and make sure your word choices are clear and concrete. The passive voice, such as “The door was opened by me,” feels hesitant and wordy. On the other hand, the active voice, or “I opened the door,” feels strong and concise. Each word in your paper should do a specific job. Try to avoid including extra words just to fill up blank space on a page or sound fancy. For instance, “The author uses pathos to appeal to readers’ emotions” is better than “The author utilizes pathos to make an appeal to the emotional core of those who read the passage.”

Proofread for spelling, grammatical, and formatting errors. After you’ve revised your paper’s organization and content, fix any typos and grammar issues. Again, it’s helpful to put your paper aside for a while so you can proofread it with fresh eyes. Read your essay out loud to help ensure you catch every error. As you read, check for flow as well and, if necessary, tweak any spots that sound awkward.

Ask a friend, relative, or teacher to read your work before you submit it. Have 1 or 2 people assess your draft’s organization, persuasiveness, spelling, and grammar. New readers can help you find any mistakes and unclear spots that you may have overlooked. It’s wise to get feedback from one person who’s familiar with your topic and another who’s not. The person who knows about the topic can help ensure you’ve nailed all the details. The person who’s unfamiliar with the topic can help make sure your writing is clear and easy to understand.

Comments

0 comment