views

The fallout of last week’s revelations that Google continues to collect your location data even when the Location History feature is turned off, can finally be felt. A man in California, Napoleon Patacsil from San Diego, has sued Google. Patascil has gotten his attorneys to file a class action lawsuit against the tech company, in the federal court in San Francisco.

“Google expressly represented to users of its operating system and apps that the activation of certain settings will prevent the tracking of users’ geolocations. This representation was false. Despite users’ attempts to protect their location privacy, Google collects and stores users’ location data, thereby invading users’ reasonable expectations of privacy, counter to Google’s own representations about how users can configure Google’s products to prevent such egregious privacy violations,” the lawsuit filed by Patacsil’s attorneys states. The lawsuit is also looking to establish an “iPhone class” and an “Android class”, in the hope to obtain class action status—though it could take a while before a verdict about the sufficient case for a class does exist.

The class action label could prove critical. The plaintiff in the case, Patascil, is not only seeking damages from Google from the perceive deception, but also wants the court to get Google to destroy all the tracking location data that has been acquired for him and all the class members of the lawsuit. That will be all Android and iPhone users, us lot.

Google Location Services is a closed source system service that is a part of Android and indeed some of Google’s location based apps. On Android, this cannot be uninstalled, disabled or removed from the phone. The Location Services combine data from multiple sources to determine the phone’s, and therefore the user’s location. The data is collected from a combination of sources, including the very powerful GPS hardware which all smartphones have, Wi-Fi connections and cellular network tower position. By using all this data, the recipient can pretty much put the phone and the user’s location on a map, at any given point of time.

This lawsuit comes after the Electronic Privacy Information Center, an independent non-profit research based in Washington, D.C., has been urging the United States Federal Trade Commission to further examine whether Google is in breach of its 2011 consent decree, in which Google agreed to implement a comprehensive privacy program to protect consumer data after it was after it was found to have used deceptive tactics and violated its own privacy promises to consumers when it launched its social network, Google Buzz, in 2010. In that settlement in 2011, Google had agreed to not misrepresent anything related to "(1) the purposes for which it collects and uses covered information, and (2) the extent to which consumers may exercise control over the collection, use, or disclosure of covered information." The latter states, “Google has misrepresented the extent to which users have control over the location data that the company has already acquired. A user who turned off the “Location History” setting believed that Google would no longer store their location information. And Google’s subsequent changes to its policy, after it has already obtained location data on Internet users, fails to comply with the 2011 order. The company cannot retroactively “change the terms of the bargain.” If the company wishes to revise its policies, it may in some circumstances, do so prospectively. But to acquire user data under one representation and then to use that same data for a purpose that is clearly in conflict is a ‘bait and switch’ plain and simple.”

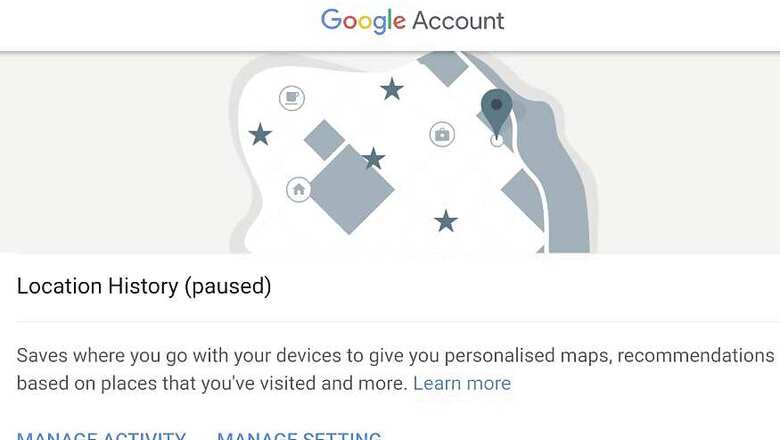

This time around, Google is under fire for the tracking user location even when the Location History feature was explicitly turned off by users. In response, the company had quietly changed the descriptions and wordings, in effect to say, “some location data may be saved as part of your activity on other services, like Search and Maps.” In many ways, this is completely the opposite of what the 2011 promises meant. And completely the opposite of what you expected when you turned off location services.

The first red flag, in many ways was raised by K. Shankari, a graduate researcher at UC Berkeley, back in May. “My speculation is that Google Location Services shares the location data that it collects for crowdsourcing with Google Maps, which which in turn prompts users for data that cannot be automatically sensed in the background, such as perceptions and photos. There does not appear to be a way to turn off this sharing, even in the new privacy policy and controls. The only recourse is to turn off Google Location Services entirely, which impacts not just the Google Maps app, but the entire phone functionality,” he had written at the time.

It is not as if Google made it easy for you to manage your location setting preferences. Yes, you could go into Activity Controls for your account via your phone or a web browser on a PC and turn off the Location History slider. Considering how it was described all along, no user can be faulted for assuming that turning this off meant that the location tracking was completely turned off. But to get to this, you need to open the Google app on your phone -> Settings -> Accounts and Privacy -> Google Activity Controls, from the midst of what literally seem like hundreds of other control options to wade through.

This lawsuit could potentially affect millions of smartphone users, basically anyone who uses an Android smartphone running Google’s Android operating system with Google’s own apps or an Apple iPhone with Google apps installed by the user.

It will now be up to the federal court in San Francisco to assess whether Google did or did not clearly obtain consent from users. Is it good and proper to have the terms and conditions spread across multiple different pages or different apps, and expect the consumer to put that all together to understand the real meaning and perhaps any potential hidden meaning too?

The fact that Google changed the wording of the location tracking policy last week does indicate that there is an acceptance about the confusion.

The latest lawsuit will bring more attention on to Google. The lawmakers have taken note. Sen. Richard Blumenthal (Democrat -Connecticut) has already weighed in with his views in a tweet, “It should be simple—“off” means “off.” Google’s relentless obsession with following our every movement is encroaching & creepy. I’ve called for an FTC investigation into its persistent privacy invasions.” Sen. Blumenthal and Sen. Edward J. Markey (Democrat -Massachusetts) asked the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to look into Google's location tracking. In May this year, the two lawmakers wrote to the FTC, saying, “Google’s opaque privacy setting have allowed the company to develop an intimate understanding of personal lives as they watch their user’s seek the support of reproductive health services, engage in civic activities, or attend places of religious worship. All that it takes for users to expose themselves to this collection is to once allow an ambiguously described feature, for example when trying to display photos on a map on the Google Photo service, silently enabling the feature across devices with no expiration date.”

This is perhaps just the start of a new battle for Google, and the attention is even more relentless, considering how important data privacy has become as an issue for lawmakers and how important it has become for consumers.

Also read: Google Sued For Tracking You Even When The Location History Feature Was Turned Off

Comments

0 comment