views

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s spiritual southern sojourn to visit temples that have a deep connect with the Ramayana has also piqued interest in a special version of the epic shared by the adivasis (tribals) of Kerala’s Wayanad district.

Wayanad has a tribal culture deeply rooted in the Ramayana lore. The region has the highest tribal population in Kerala— 18 per cent of the people in the district are adivasis.

Wayanadan Ramayanam is an oral traditional version set over two states: Wayanad in Kerala and neighbouring Karnataka’s Kodagu.

Those who have heard this beautiful tribal version say that their unique narration will not only link you to the lives of the adivasis, their trials and tribulations, but Rama and Sita and other characters also live this very life, just as any marginalised community would.

Over several centuries, generations have formed their own versions of the Ramayana that have been delivered orally, different from Valmiki’s epic.

So how different is this from Valmiki’s Ramayana?

The characters of Valmiki’s Ramayana such as Ram, Sita, and others also appear in the Wayanadan Ramayana. In one oral version, tribal gods and goddesses of Wayanad are also characters who feature as part of this Ramayana, explains Dr Azeez Tharuvana, a Malayalam scholar who has researched and written an exhaustive book called Wayanadan Ramanayanam.

Tharuvana, who is an assistant professor at the Farook College in Kozhikode has spent a large part of his career researching this distinct tribal version of the Indian epic.

For example, in the Adiya Ramayana (the oral version of the text that prevails among the Adiya tribe of Wayanad), there are popular characters from local legends and folklores, such as Valliyoorkavu Bhagavathi, Pulpally Bhagavathi, Pakkatheyyam, Tirunelli Perumal, Siddhappan, Nenjappan, and Mathappadeva. Similarly, in Chetty Ramayana (the text used by the Wayanadan Chettis), there are characters like Athirukaalan, Arupuli, Kandan Puli, Dammadam, Karikalan, and Thamburatti, he explains.

Tharuvana emphasises that the distinctiveness of both oral and written Ramayana versions in India and other Asian countries lies in their close integration with local cultures.

“Ramayana stories that have transcended different regions carry the unique characteristics of those places and cultures in their retelling. Essentially, diverse castes, religions, and local communities have personalised the Ramayana. In the Ramayanas from Wayanad, local cultural, societal, and environmental influences play a prominent role,” he explains.

One of the most distinct tribal versions of Ramayana is the Adiya Ramayana. Here Sita is a woman who hails from Pulpally in Wayanad and belongs to the Adiya tribe. Lanka is not a kingdom across the ocean but is located near a river.

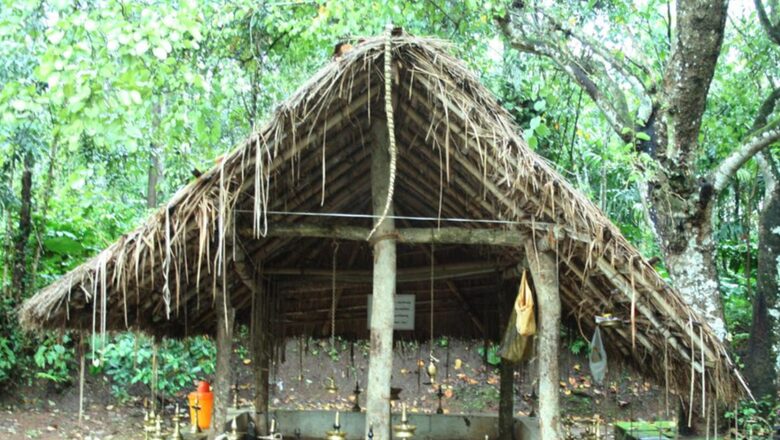

“There is a Valmiki shrine near Pulpally. It is also a spot where Sita is supposed to have vanished under the earth. Towards the end of the story, Ram, Lakshman, Hanuman, and other tribal gods go to Iruppu, a village in Karnataka, where now stands a temple dedicated to Sita. And all other characters like Ram, Lakshman, and Hanuman are lower in status than Adiya tribal gods like Siddappa, Nenjappa, and Mathappa,” Tharuvana tells News18.

Another notable difference in Adiya Ramayana is the introduction of new episodes not found in other versions. For instance, there’s a unique scene where tribal chiefs tie Ram and Lakshman to a tree, questioning Ram about abandoning a pregnant Sita. This interrogation is a narration that is exclusive to Adiya Ramayana.

Adiya Ramayana stands out as the only version without a battle scene, deviating from the typical narrative.

Tharuvana also observes that the Adiya Ramayana highlights social issues specific to the tribe. The lack of personal property among the Adiyas is a significant concern.

There are also instances in the Wayanad tribal versions of the Ramayana that talk of how Sita served Kaapi (coffee) to Ram or how Hanuman set fire to Lanka using kerosene. These depictions reflect how the tribals have infused their day-to-day activities and environment into their version of the epic.

Researchers who have been working with the adivasis who are part of disseminating their oral tradition of the Ramayana story point out that over 30 places across Wayanad district have been named after the “tribal version” of the epic. The adivasis believe Valmiki’s ashram was situated in Ashram Koli. Other places around Wayanad are named Yogimoola, Rampalli, Sita Mound, Poothadi, and Choorupura.

Kannuneer Puzha (River of Tears), a large water body, as the legend goes, is the place where Sita sat down crying after being exiled. Today, this is a river that flows as a tributary of the Kabini river, which originates in Karnataka and is also called Kannaram Puzha.

Another example, Tharuvana says, is the legend associated with Jadayattakkavu, near Pulpally town. The adivasis in the region believe that here Sita’s tresses touched the earth. Jadayatta Kavu is also the site of the famous Pulpally Seetha Devi Lava Kusa Temple.

“They believe that as Sita was sinking into the earth, Lord Ram held onto her hair…So she is venerated here as Chedattilamma (‘jada/cheda’ means hair, atta, ‘to move’),” the researcher said.

Ponkuzhi is the place where adviasis believe Ram sent Sita away on exile after he banished her from the kingdom. And Ambukuthy Hills in Ambalavayal is said to be the place where Ram and Lakshman fought the demoness Thadaka.

Prof Tharuvana also explains how there are other instances in the oral Wayanadan Ramanayam where it is believed that Lord Ram, under the guidance of munis, offered prayers at Thirunelli Temple to achieve victory over Ravana.

“There is another legend that Lord Ram, along with Lakshman, Bharath, and others, conducted the last rites of their father King Dasarath in the Papanashini river. Yet another legend claims that Parasuram, after learning that his father was killed, conducted his last rites in Thirunelli. It is not only characters but also natural phenomena and landscapes that were planted in the settings of Wayanad,” he adds.

Just as the holy river Ganga flows through Kashi, the river Papanashini flows through Thirunelli, which is known as the Kashi of the south.

Chetty Ramayana, another tribal narrative by Wayanadan Chettis, depicts Wayanad as Panchavati in the Ramayana.

Originating from nearby Tamil Nadu, including Coimbatore and the Nilgiris, the Wayanadan Chettis, unlike tribal communities, are literate and have a strong connection to temple culture and literature.

Tharuvana explains how the traditional deities of the Wayanadan Chetty community, such as Athirukalan, Arupuli, Kandan Puli, Bammathan, Kaikkolan, and Thampuratty, play significant roles in the narrative.

These forest goddesses inform Ram and Lakshman that the horse in the Ashwamedha Yagna has been reined in by Lava and Kusa. The uniqueness of the Chetty Ramayana lies in its compelling and intriguing presentation of a story believed to have occurred centuries ago.

In another telling, Wayanad was once an open field for demons, striking fear into everyone. These demons would abduct young women and take them deep into the forest. Kusa, Rama’s son, is said to have saved Chandika Devi, the daughter of Erumapally Chetty, from the demons, leading to the eventual marriage between Chandika Devi and Kusa. With Hanuman’s intervention, Lava, Kusa’s brother, was later married to Sunitha Devi, Chandika Devi’s sister.

So entrenched is Ramayana’s imprint on Wayanad, that the district tourism promotion council has been actively promoting the Ramayana Trail to draw visitors.

Comments

0 comment