views

Helping a Hoarder

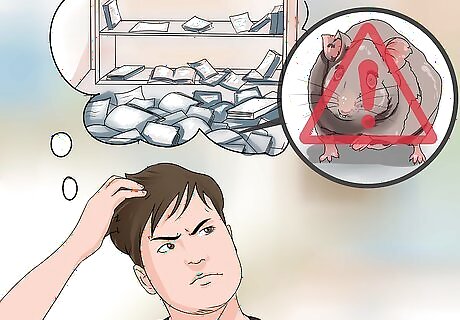

Recognize hoarding behaviors. People who struggle with excessive hoarding save excessive items in a disorganized manner, often creating a dangerous living environment. People who hoard are often unable to discard any items, even if they have no monetary value. They save these items out of sentimentality or due to fear that they may need the item in the future. Hoarders often create rooms in their homes that can no longer be used as they are intended due to an accumulation of clutter. Hoarders often collect newspapers, magazines, brochures, and other documents that contain information so that they can read and digest the information at a later date, but many do not get around to actually reading the papers. Hoarders attach strong emotions to objects and feel that possessions offer them a sense of comfort or security. They may feel as though letting go of a possession is losing a part of themselves.

Understand underlying issues that lead to hoarding. The reasons behind hoarding vary from person to person, but hoarders consistently show an emotional or psychological connection to the items. They also exhibit a resistance to thinking or talking about the extent of the clutter.

Check on the hoarder frequently. If you do not live with the hoarder, be sure to stop by to check on and socialize with him when you can. You should use your visits to determine whether conditions are improving or worsening. You may need to evaluate whether the hoarder has reached a point of being a danger to himself.

Identify the problem. Many hoarders may admit to being “pack rats” or wanting to keep things, but they do not understand concerns about health or safety. They may not see their behavior as problematic, and often do not realize the impact that their behaviors have on others.

State your concerns in a non-judgmental manner. You should communicate your concerns for the hoarder’s health and safety, but try not to sound judgmental. Try focusing on the health risks, including mold, dust, and cleanliness. You can also focus on environmental safety, pointing out fire hazards and blocked exits. Try not to spend too much time focusing on the clutter or objects themselves, as this will likely cause the hoarder to become defensive. For example, you might say “I care about you, and I am concerned for your safety. The apartment has become quite dusty and moldy, and because of the large piles everywhere, I don’t think you could get out quickly and safely in an emergency.”

Ask for permission to help. Organizing or throwing away items without the hoarder’s permission can give him serious anxiety. Instead, assure him that no one is going to enter his home and throw away his things. Offer to help sort through items or seek input from a professional organizer. Ultimately, the hoarder needs to maintain control of the decision making about what to do with items. Try to use the language the hoarder uses to refer to the clutter. If the hoarder call the items his collection or his things, mirror the language he uses to seem more non-confrontational.

Ask questions about the collected items. You can gather information and try to help the hoarder by finding out more about how and why he has saved and organized the items in his possession. Try to enforce the hoarder’s feeling of control; remember, you’re trying to help, not tell him what to do. Some examples of questions to ask include: “I notice there are a lot of books in the hallway. Why did you decide to put them there?” “I’m concerned these could be a tripping hazard in an emergency. Do you have somewhere else we could put them?” “Do you have any thoughts about how we could make this area safer?”

Help the hoarder establish goals. Productive goals that will help the hoarder will focus on improving the quality of life and the functionality of the living space. Be sure to make the goals measurable. Do not focus the goals on negatives (get rid of all of this junk). Do not set vague goals like “get the house clean and organized.” A better goal would be “clear the hallway and make all exit doors easily accessible.” Start with the bigger concerns about health and safety, then move on to smaller goals that will improve quality of life.

Avoid causing distress. It is important to be gentle and patient when working with a hoarder. Remember that hoarding is an emotional issue, and simply cleaning for a hoarder does not solve a long-term problem. You also risk violating the trust of the hoarder and losing any ground you may have gained with him. Do not nag, force, or punish someone who is struggling with hoarding. Do not argue or yell at a person who is hoarding. Instead, try to team up with him to work towards a goal together.

Praise improvements. Whenever the hoarder makes an effort to improve an area, praise him for his progress. You may notice a small area that has been de-cluttered or be able to see a patch of wall that wasn’t visible before. No matter how small the improvement is, it should elicit praise and positivity from you.

Find a motivation to improve. While it can be difficult to externally motivate someone, you may be able to find a way for the hoarder to become motivated to improve. For example, you might suggest that he can host a party or a social gathering. This may encourage him to improve his living area before other people come over.

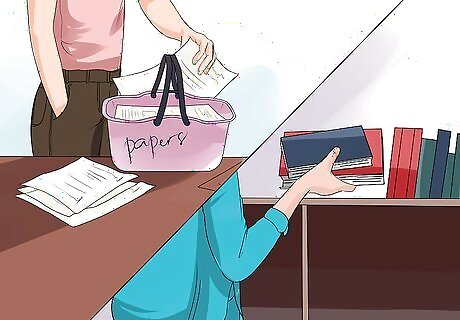

Develop a plan. A person who struggles with hoarding may not have the skills to organize and sort items themselves. If he is open to help, offer to help him organize and sort through items. You may want to gather storage containers, shelving units, boxes, and labels before you start. Start by labeling boxes or bags with “keep,” “trash,” and “donate.” You probably need to make a space to pile items to think about or come back to. Group similar items together. Seeing a large quantity of a single thing may help the hoarder make peace with reducing the number of a specific item. For example, if he has 100 boxes of tissue, he may be willing to reduce the number of boxes to 50. This is a small step, but it will help. Categorize “want” and “don’t want.” You can start the “don’t want” pile with something that is an easier decision, like food items that have expired or dead plants. Discuss where things that are to be kept will go. This may be a specific room in the house or a storage unit.

Know the consequences of extended hoarding. Two key indications of hoarding are social or occupational impairment and an unsafe living environment. Left unchecked, hoarding can lead to an increasingly unsafe environment, health concerns, financial consequences, and strained relationships. Specific hazards that can result from hoarding include: blocked exits creating fire hazards or building code violations increased health risk for environmental irritants such as mold and dust as well health code violations decreased hygienic habits due to inability to perform hygienic tasks such as bathing increased isolation and avoidance of socializing strained family relationships, child neglect, and separation or divorce

Give it time. The process of cleaning and organizing a huge accumulation of items will take a significant amount of time. This is not a problem that can be fixed in one day. It will take a long period of small, persistent efforts to organize a hoarder’s home.

Living with a Hoarder

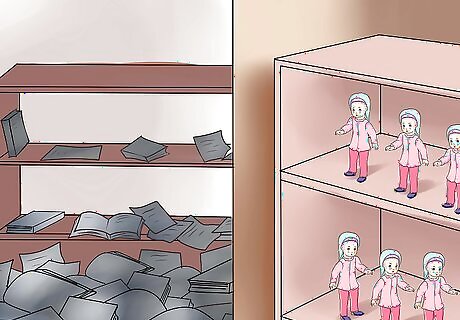

Differentiate hoarding from collecting. Collectors are people who acquire specific items. Collectors will often display these items in an organized manner. Hoarders, on the other hand, save random items and create hazardous mounds of clutter. People who collect one type of thing—like dolls, stamps, antique end tables, figurines, etc—and organizes them in a particular way are not hoarders; they are collectors. Do not let your own feelings about cleanliness, organization, and whether to keep important or significant items influence you to label someone who is disorganized or a collector as a hoarder.

Be patient. Living with a hoarder can be especially difficult, as he may become upset any time you try to clean or organize. It may be particularly difficult to get a hoarder with whom you live to assist in cleaning out clutter.

Focus on the shared nature of your home. You need to remind the hoarder that you both share a living environment. Emphasize making improvements to “our” living environment. Try not to separate “his things” from the shared space of the home.

Offer a compromise. If your loved one is adamant that he “needs” to keep all of his things, try to establish acceptable limits in shared spaces. You may want to keep common spaces such as the living room and kitchen free of clutter, designating a particular room or rooms for storage. You can provide space for your loved one’s things while addressing your concerns about the hoarding and maintaining your own need for a less cluttered environment.

Do not throw away hoarded belongings. Discarding belongings, even if you view them as junk, can create a rift between you and your loved one. It can cause you to lose any ground you’ve made in helping the hoarder become more organized.

Encouraging Professional Help

Recognize risk factors for hoarding behavior. There are many complex factors that contribute to hoarding behavior, but many hoarders have common risk factors. Hoarders often have a family member who is also a hoarder, experience a brain injury, or undergo a stressful life event such as the death of a loved one. Some hoarding behavior also results from co-occurring mental health conditions, such as: anxiety trauma depression attention deficit disorder or hyperactivity alcohol abuse being raised in chaotic homes schizophrenia dementia excessive-compulsive disorder personality disorders

Offer to help hire an outside party to assist with the organization. It may be emotional or embarrassing for the hoarder to have a family member sorting through his things. He may be more open to having a professional organizer or an objective outsider help.

Encourage the hoarder to seek therapy. Cleaning alone will not solve most hoarding problems. Individuals suffering from hoarding disorder often need a combination of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), skills building, and medication. The particular method of CBT used with hoarders is called exposure and response prevention, which desensitizes participants to the things that they fear and reduces their responses to that fear. Medications prescribed for hoarders are often SSRI antidepressants that are used to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder as well. Some of these medications include Anafranil, Zofran, Lexapro, Zoloft, Prozac, and Paxil.

Offer to attend therapy together. If you live with the hoarder or if he is a family member, you may both benefit from couples therapy, family therapy, or group therapy. Attending therapy together may encourage him to go to his therapy sessions.

Contact a doctor or mental health professional. A physician may be able to give you advice about how best to work with a hoarder or convince him to seek help through therapy. Some communities also offer assistance for hoarding or mental health issues through their public health agencies. It may be necessary for public health or animal welfare agencies to intervene with the hoarder.

Comments

0 comment