views

X

Trustworthy Source

Mayo Clinic

Educational website from one of the world's leading hospitals

Go to source

When this happens, your bladder presses on your vaginal wall, which is called a prolapsed (or cystocele) bladder. Research suggests that as many as 50% of women have some form of bladder prolapse after pregnancy, so it's a fairly common problem.[2]

X

Trustworthy Source

Harvard Medical School

Harvard Medical School's Educational Site for the Public

Go to source

If you're worried you have a prolapsed bladder, talk to your doctor because you have a range of treatment options.

- Feel for a bulge of tissue in your vagina. You may feel like you’re sitting on a ball or an egg.

- Pain, pressure, and/or discomfort in the lower abdomen, pelvic area, or vagina may indicate a prolapsed bladder.

- See a physician to determine the best treatment option for you. If your pain is minimal, they may prescribe options like Kegel exercises and physical therapy.

Recognizing the Symptoms of a Prolapsed Bladder

Feel for a bulge of tissue in your vagina. In serious cases, you may be able to feel your bladder descend into your vagina. When you sit down, it may feel like you are sitting on a ball or an egg; this feeling may disappear when you stand up or lie down. This is the most obvious symptom of a cystocele, and you should see your primary care physician or gynecologist as soon as possible. This feeling is generally considered a sign of a severe prolapsed bladder.

Note any pelvic pain or discomfort. If you have any pain, pressure, or discomfort in your lower abdomen, pelvic area, or vagina, you should see a doctor. Any number of conditions, including a prolapsed bladder, could cause those symptoms. If you have a cystocele, this pain, pressure, or discomfort may increase when you cough, sneeze, exert yourself or otherwise place pressure on the muscles of your pelvic floor. If this is the case, be sure you mention it to your doctor. If you have a prolapsed bladder, you may also feel like something is falling out of your vagina.

Consider any urinary symptoms. If you tend to leak urine when you cough, sneeze, laugh, or exert yourself, you have what’s known as “stress incontinence.” Women who have given birth are particularly susceptible, and a prolapsed bladder can be a major cause. See your doctor to resolve the issue. Notice as well if you've experienced any changes when you urinate, including difficulty initiating a stream of urine, incomplete emptying of the bladder (also known as urinary retention), and increased urinary frequency and urgency. Note if you've had frequent bladder infections, or urinary tract infections (UTIs). "Frequent" is defined as having more than one UTI in a six-month period. Women with cystoceles often wind up with frequent bladder infections, so it's worth paying attention to the frequency of your UTIs.

Take pain during sexual intercourse seriously. Pain during sex is called “dyspareunia” and can be triggered by a number of physical conditions, including a prolapsed bladder. If you are dealing with dyspareunia, you should see your primary care physician or gynecologist as soon as possible. If pain during intercourse is a new development for you, and you’ve recently delivered a baby vaginally, then a prolapsed bladder is a particularly likely cause. Don’t delay seeing your doctor.

Monitor your back pain. Some women with cystoceles also experience pain, pressure, or discomfort in the lower back area. Back pain is a very general symptom that could mean many things – or nothing serious at all – but it makes sense to schedule an appointment with your doctor. This is especially the case if you are experiencing any of the other symptoms.

Know that some women have no symptoms at all. If your case is a mild one, you may not notice any the above symptoms. Some cystoceles are first discovered during routine gynecological examinations. However, if you exhibit or experience any of the symptoms described above, you should consult your primary care physician (PCP) or gynecologist. If you do not experience symptoms there is often no need for treatment.

Understanding the Causes of a Prolapsed Bladder

Know that pregnancy and childbirth is the most common cause of a prolapsed bladder. During pregnancy and childbirth, your pelvic muscles and supportive tissues are strained and stretched. Since these are the muscles that hold your bladder in place, serious stress or weakness on them can allow the bladder to slip down into the vagina. Women who have been pregnant, especially if they had multiple vaginal births, are at high risk for the development of cystoceles. Even women who delivered by cesarean are at risk.

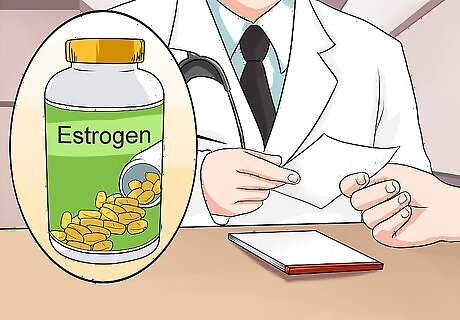

Recognize the role of menopause. Postmenopausal women are at significant risk for a prolapsed bladder due to reduced levels of the female sex hormone estrogen. Estrogen is partly responsible for maintaining the strength, tone, and resilience of your vaginal muscles. As a result, the low levels of estrogen accompanying the transition into menopause cause these muscles to become thinner and less elastic, which leads to overall weakening. Note that this drop in estrogen takes place even if you enter menopause through artificial means, as with the surgical removal of your uterus (hysterectomy) and/or ovaries. These surgeries not only cause damage to the pelvic area, but also cause changes in estrogen levels. Therefore, though you may be younger than most menopausal women and otherwise healthy, you are still at risk for a cystocele.

Be aware of muscle strain as a factor. Intense straining or heavy lifting can sometimes trigger a prolapse. When you strain the muscles of your pelvic floor, you risk triggering a prolapsed bladder (especially if the muscles of your vaginal wall have already been weakened by menopause or childbirth). Types of straining that can cause a cystocele include: Lifting very heavy objects (including children) Chronic, intense coughing Constipation and straining during bowel movements

Consider your weight. If you are overweight or obese, your risk of a prolapsed bladder is increased. The extra weight places additional strain on the muscles of your pelvic floor. Whether someone is overweight or obese is determined by using the body mass index (BMI), an indicator of body fatness. BMI is a person's weight in kilograms (kg) divided by the square of the person's height in meters (m). A BMI of 25-29.9 is considered overweight, while a BMI greater than 30 is considered obese.

Diagnosing a Prolapsed Bladder

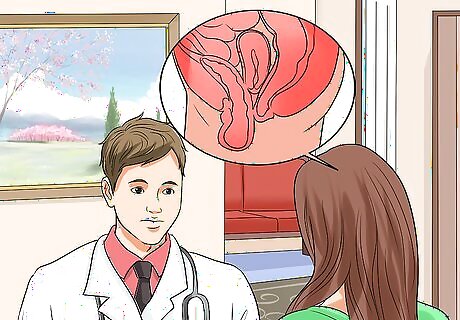

Make an appointment with a physician. If you think you may have a prolapsed bladder, schedule an appointment with your primary care physician or gynecologist. Be prepared to give your doctor as much information as possible, including a complete medical history and a detailed description of your symptoms.

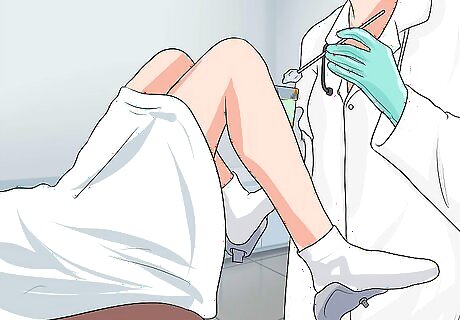

Have a pelvic exam. As a first step, your doctor will probably perform a routine gynecological exam. In this exam, the cystocele is detected by applying a speculum (a tool for inspecting body orifices) against the posterior (back) vaginal wall while you lie back with your knees bent and ankles supported by stirrups. The physician will likely ask you to "bear down" (as if you were pushing during childbirth or having a bowel movement) or cough. If a cystocele is present, the doctor will see or feel a soft mass bulging into the anterior (front) vaginal wall when you strain. A bladder that has ended up in the vagina is considered positive diagnosis of a prolapsed bladder. In some cases, in addition to performing the standard pelvic exam, your doctor may want to examine you standing up. It can be beneficial to evaluate a prolapse from different positions. If your doctor notices a prolapse in the back wall of your vagina, she is likely to also perform a rectal exam. This will help her determine the strength of your muscles. You don't need to prepare for this examination in any way and it should not take very long. You may feel slight discomfort during the pelvic exam, but for many women this is just a routine exam much like having pap smears.

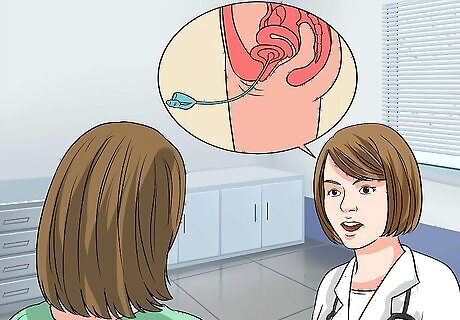

Have further testing if you are experiencing bleeding, incontinence, or sexual dysfunction. Your doctor will likely recommend tests known as cystometrics or urodynamics. A cystometric study measures how full your bladder is when you first feel the need to urinate, when your bladder feels "full," and when your bladder is actually completely full. Your doctor will ask you to urinate into a container that is connected to a computer, which will take some measurements. Then you will lie on an examination table and the doctor will insert a thin, flexible catheter into your bladder. Urodynamics is a set of tests. It includes measured voiding (aka uroflow), which will time how long it takes you to start urinating, how long urination takes to complete, and how much urine you produce. It also includes cystometry, as mentioned above. It will also include a voiding or emptying phase test. In most urodynamics tests, your doctor will place a thin, flexible catheter into the bladder, which will remain in place as you urinate. A special sensor will gather data for your doctor to interpret.

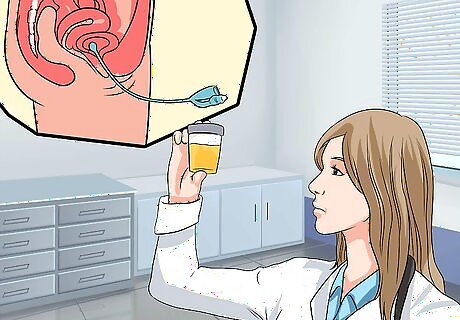

Talk to your doctor about additional testing. In some cases, usually when your prolapse is more severe, your doctor may recommend additional tests. Common additional tests include: Urinalysis - In a urinalysis, your urine will be tested for signs of infection (such as a UTI). The doctor will also test your bladder to see if it empties completely. This is done by inserting a catheter (tube) into a woman's urethra to remove and measure the amount of remaining urine after voiding, the post-void residual (PVR). A PVR of more than 50-100 milliliters is diagnostic for urinary retention, one of the symptoms of a prolapsed bladder. Ultrasound with PVR - An ultrasound test sends out sound waves that bounce off the bladder and back to the ultrasound machine, producing in the process an image of the bladder. This image also shows the amount of urine remaining in the bladder after urination, or voiding. Voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) – This is a test in which a doctor takes x-rays during urination (voiding) to view the bladder and evaluate problems. A VCUG shows the shape of the bladder and analyzes urine flow to pinpoint any potential blockages. The test can also be used to diagnose stress urinary incontinence masked by a cystocele. It is important to make this dual diagnosis, as the patient will also need an incontinence procedure in addition to a cystocele repair (if surgery is needed).

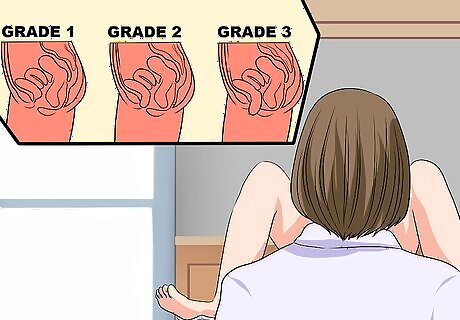

Get a specific diagnosis. Once your doctor confirms the presence of a prolapsed bladder, you should ask for a more detailed diagnosis. Cystoceles are divided into categories based on severity. The best course of treatment will depend on what kind of cystocele you have, as well as the symptoms it is causing in your life. Your prolapsed bladder may fall into any of the following “grades”: Grade 1 prolapses are mild. If you have a Grade 1 cystocele, only part of your bladder is descending into your vagina. You may exhibit mild symptoms such as slight discomfort and urine leakage, but some women don't exhibit any symptoms. Treatment may consist of Kegel exercises, rest, and avoidance of heavy lifting or straining. If you are postmenopausal, estrogen replacement therapy is also a consideration. Grade 2 prolapses are moderate. If you have a Grade 2 cystocele, the entire bladder descends into the vagina. It may reach so far that it touches the vaginal opening. Symptoms such as discomfort and urinary incontinence become moderate. Surgery to repair the cystocele may be warranted, but you may be able to get adequate symptom relief with a vaginal pessary (a small plastic or silicone device that you place inside your vagina to hold the walls in place). Grade 3 prolapses are severe. If you have a Grade 3 cystocele, part of the bladder actually bulges through the vaginal opening. Symptoms such as discomfort and urinary incontinence become severe. Cystocele repair surgery and/or pessary as with a grade 2 cystocele is required. Grade 4 prolapses are complete. If you have a Grade 4 cystocele, the entire bladder descends through the vaginal opening. In these cases, you may experience other severe problems, including uterine and rectal prolapses.

Treating a Prolapsed Bladder

See if you need treatment. A Grade 1 prolapsed bladder usually requires no medical treatment as long as it is not accompanied by pain or discomfort for the sufferer. Check with your physician as to whether she recommends medical treatment or more of a "wait-and-see" approach. If your symptoms do not bother you very much, your doctor is likely to recommend basic treatment approaches including Kegel exercises and physical therapy. Note that your physician may recommend that you back off certain activities, like weight lifting or other activities that put strain on your pelvic muscles. It's still healthy to exercise regularly, though. You should also know that how your symptoms affect your quality of life is a key factor in deciding on treatment. For example, you may have a severe prolapse but are not troubled by your symptoms. In this case, you could talk with your doctor about less severe treatment options. On the other hand, you might have a mild prolapse, but the symptoms cause you significant distress or inconvenience. You could talk with your doctor about a more aggressive approach.

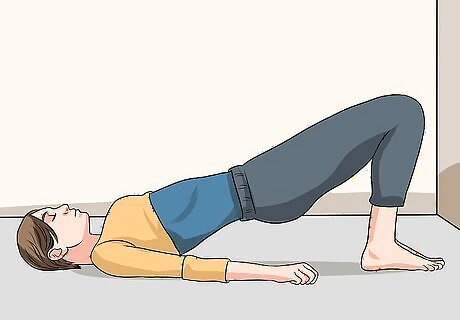

Practice Kegel exercises. Kegel exercises are performed by contracting the muscles of your pelvic floor (as if you were attempting to stop the flow of urine), holding them for a brief period, and then releasing them. Regular performance of these exercises, which require no special equipment and can be performed anywhere (including while waiting in line, at a desk, or relaxing on the couch), can strengthen your muscles. In mild cases, they can keep your prolapsed bladder from descending further. To perform Kegel exercises: Contract, or tighten, the pelvic floor muscles. These are the muscles used to stop the flow of urine when urinating. Hold the contraction for five seconds and then relax for five. Work up to holding the contraction for ten seconds at a time. Your goal is three to four sets of 10 repetitions of the exercises daily

Use a pessary. A pessary is a small, silicone device that, when inserted into the vagina, holds the bladder (and other pelvic organs) in place. Some are made for you to insert yourself; others need to be inserted by a doctor. Pessaries come in a variety of shapes and sizes and a healthcare professional can help a woman choose the most comfortable fit. Pessaries can be uncomfortable, and some women have trouble keeping them from falling out. They may also cause vaginal ulceration (if not correctly sized) and infection (if not routinely removed and cleaned on a monthly basis). You will likely need a topical estrogen cream to prevent damage to your vaginal walls. Despite these disadvantages, a pessary can be a valuable alternative, particularly if you wish to postpone or are not a good candidate for surgery. Talk to your doctor, and weigh the pros and cons for your particular case.

Try estrogen replacement therapy. Because a reduced level of estrogen is so frequently responsible for weakened vaginal muscles, your doctor may suggest estrogen therapy. Estrogen can be prescribed as a pill, vaginal cream, or ring inserted into the vagina in an effort to strengthen weak pelvic floor muscles. The cream doesn't absorb very well and thus is strongest on the area where it is applied. Estrogen therapy does have risks. Women with certain types of cancer should not take estrogen, and you should discuss the potential dangers and benefits with your doctor. In general, topical estrogen treatments are less risky than oral, “systemic” estrogen treatments.

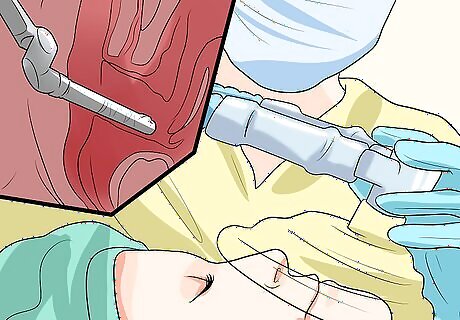

Undergo surgery. If other treatments do not work, or if your cystocele is very severe (Grade 3 or 4), your doctor may recommend surgery. Surgery works better for some women than others. For example, if you have plans for future children, you may wish to postpone the surgery until after your family is complete to avoid prolapse happening again after childbirth. Older women may also have higher risks associated with surgery. A common surgical treatment for prolapse is vaginoplasty. A surgeon will lift your bladder into place, and then may tighten and reinforce your vaginal muscles to make sure that everything stays where it should. There are other surgical procedures to be considered, and your doctor will recommend the one she believes is best for your unique situation. A surgeon will explain the procedure and all of its risks and advantages and potential complications before the surgery. Potential complications include a UTI, incontinence, bleeding, infection, and in some rare cases, damage to the urinary retract that requires surgery to repair properly. It's also a possibility that women may experience irritation or pain during sexual intercourse after the surgery due to a suture or scar tissue inside of them. Depending on the specifics of your case, you may need either local, regional or general anesthesia. Many women can return home within one to three days post-operation and most patients can return to normal activity levels after about six weeks. If you also have a prolapsed uterus, your doctor may recommend a hysterectomy to remove it. This can be done along with the surgery. If the cystocele is accompanied by stress urinary incontinence, a simultaneous urethral suspension procedure may be needed.

Comments

0 comment