views

Getting Rid of a Frontal Lisp

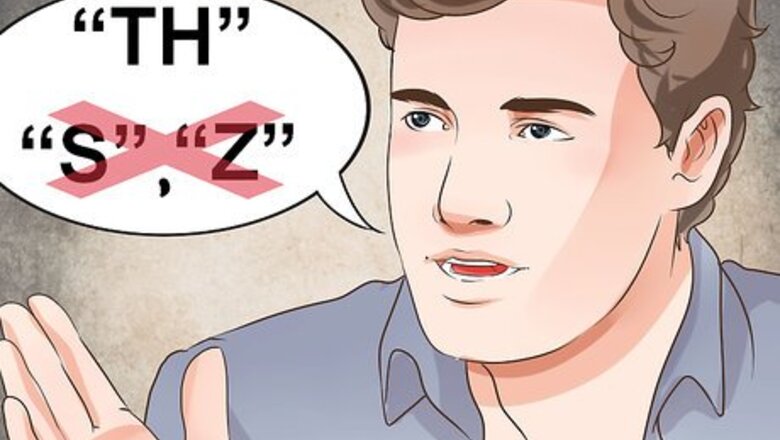

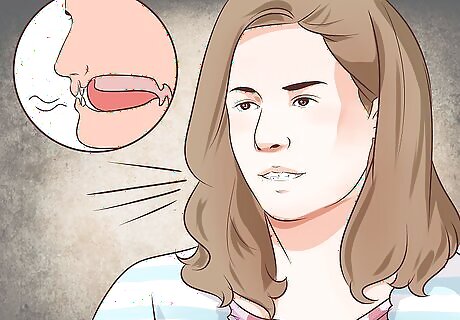

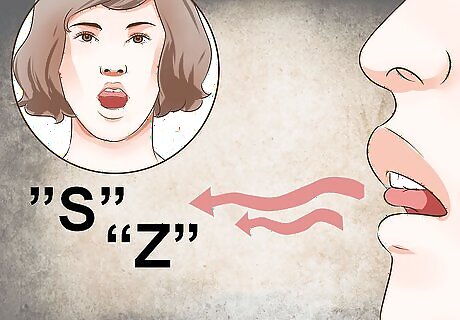

Use this exercise if you say "TH" instead of "S" or "Z." In a frontal lisp, the speaker puts his tongue forward against his teeth when he says the "S" or "Z" sound, causing a "TH" sound instead. If he has a gap between his front teeth, he may push his tongue through this gap. If you're not sure whether this describes you, look at yourself in a mirror while you make the "S" or "Z" sound. With a frontal lisp, "S" ends up sounding like the "TH" in "math" and "Z" ends up sounding like the "TH" in "father."

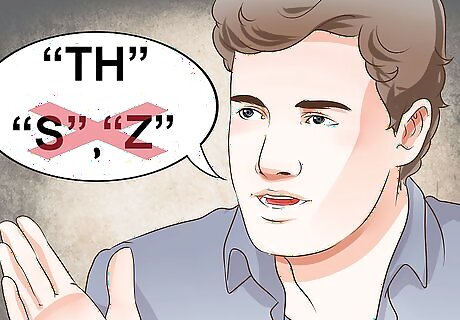

Smile at a mirror. Find a mirror in a well-lit area, so you can easily see your mouth while you speak. Smile into the mirror to display your teeth. Smiling will both make it easier to watch yourself, and help pull the tongue back slightly, where it needs to be for an "s" sound.

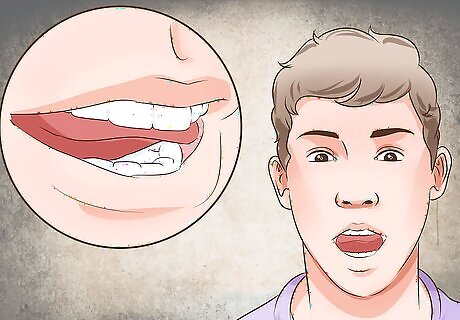

Close your teeth together. Keep your teeth together, but remain smiling with your lips apart. You do not need to clench your teeth together hard.

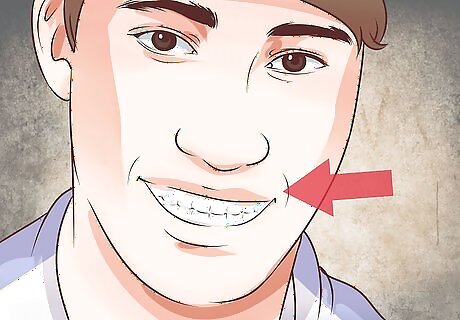

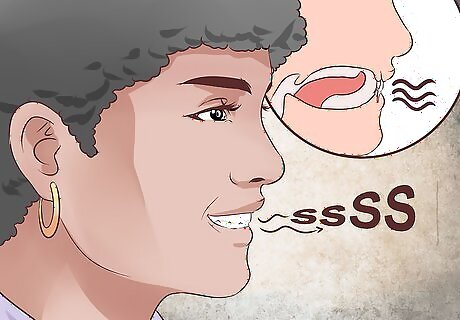

Place your tongue in the correct "S" position. Move your tongue so the tip is just behind the teeth, high up against the roof of the mouth. Don't press your tongue against your teeth, and keep your tongue fairly relaxed, not pressing hard.

Push air through your mouth. If you don't hear a hissing "S" sound, your tongue may be too far forward still. Try pulling your tongue back and smiling forward. If you can't get it, don't get frustrated. Try the next exercise below, and keep practicing often.

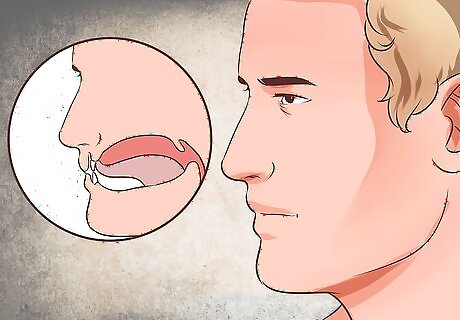

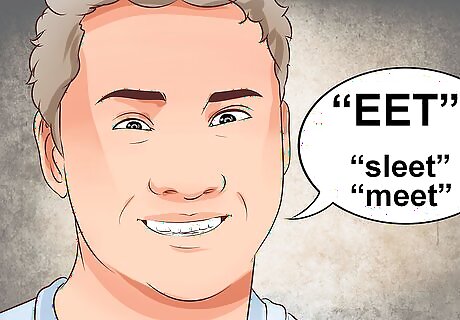

Try saying "EET" while paying attention to your tongue shape. If saying "s" is still difficult in the above exercise, try this exercise as well. Separate your teeth slightly, and press the sides of your tongue against your upper back molars (the teeth in the back top of your mouth). Smile, and try to say "EET" and keep the back of your tongue in this shape while the tip of your tongue rises to make the final "T" sound. If the back of your tongue falls when this happens, keep practicing until you can say "EET" with your tongue in this position. This is the sound "EET" as in "sleet" or "meet." If you are having difficulty keeping the back of your tongue raised, use a tongue depressor or popsicle stick to hold your tongue up while you say "EET."

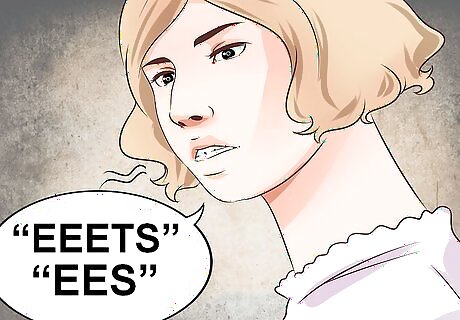

Turn the EET sound into an EETS, then an EES sound. Once you can say "EET" with your tongue in the right position, say it again while holding the "T" sound. Leave the tip of your tongue up there while you say "T-T-T-T-T-T." The flow of air past your tongue tip can turn this sound into an "S." Keep practicing this exercise until you can get an "EEETS" sound, then an "EES" sound, although you don't have to get this right on your day one. You might end up spraying some spit on this exercise!

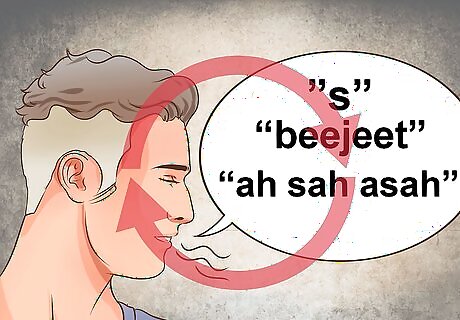

Practice these exercises frequently. Try these exercises at least once a day, and preferably several times a day. Once you can repeat the "s" sound many times in a row, try to use it in words and sentences. It might be easier for you to say nonsense words first, such as "beejseet" or "ah sah asah," then move on to reading aloud.

Ask a speech therapist for more tips. If you are still having trouble with your lisp after a few weeks, try finding a speech therapist in your area. She should be able to give you exercises that are individualized for your speech patterns, specifically designed to help you say the sounds you're trying to say.

Getting Rid of a Lateral Lisp

Use this method for lisps that produce a "slushy" sound. In a lateral lisp, the speaker's tongue is in the position for an "L" sound whenever he tries to make an "S" sound. In other words, the tip of the tongue is up against the curve where the roof of the mouth begins to rise higher. When the speaker tries to make an "S" sound, air escapes over the sides of his tongue, making a "slushy" or "spitty" sound instead. Often, "SH" as in "shoot" and "ZH" as in "massage" or "conclusion" are difficult to pronounce as well.

Put your tongue in the butterfly position. Say "knee" or "bin" and keep the vowel going, without finishing the word. During this sound, you should feel your tongue's sides rise up in your mouth, but the middle stays lowered. The tongue tip remains lowered as well, not touching anything. This tongue position looks something like a butterfly, if you picture the center of your tongue as the butterfly's body, and the sides as the raised wings.

Practice quickly putting your tongue in this position. Think of this as strength exercises for your tongue. Relax your tongue, then quickly raise it into the "butterfly position." This is making the sides of your tongue stronger, and helping them get into the habit of blocking the excess air flow that makes the "slushy" lateral lisp. Practice this as long as necessary, until you can easily reach this position.

Blow air through your mouth in this position. Keep your tongue in the butterfly position. Blow air through the groove made by your tongue instead. This should produce a sound that sounds more like an "S," or a "Z" if you vocalize while blowing.

Keep practicing this exercise, and trying to say "S" normally. Practice the butterfly position every day, and blow through it to make an airy "S" sound. Then relax your tongue again and raise the tip to just behind your teeth. Try to say an "S" sound. As your tongue becomes stronger and you become more used to the position of the sides of your tongue, your ordinary "S" sound will sound less and less slushy.

Visit a speech therapist (if necessary). If you are still having trouble with your lisp in a few weeks, try to find a speech therapist in your area. She may give you specific exercises that help you shape your mouth in the right position.

Treating a Small Child's Lisp

Learn about lisps in children. Most lisps in children are frontal lisps, in which the tongue is pushed too far forward when the child tries to make the "s" sound. Many children have this lisp, but most of them grow out of it naturally. If a child does not, professional opinion is divided on whether the child should start speech therapy for a frontal lisp at the age of four and a half, or wait until he turns seven. Consult with a doctor or speech therapist for advice specific to the child, but know that there is no need for concern if a child under four and a half years old has a lisp. If the lisp has a different form, with the tongue positioned further back, consulting a speech therapist is recommended.

Don't keep pointing out the lisp. Drawing attention to the lisp can cause embarrassment and shame, which does not help the child get rid of the lisp.

Treat allergies and sinus issues. If the child frequently has a stuffy nose, sneezing fits, or other sinus complaints, this may be affecting her speech. This is especially likely to be a cause if the child makes many sounds with her tongue pushed forward, not just "S." Seek the advice of a doctor for child-safe treatments for allergies and sinus infections.

Stop thumb sucking habits. While thumb sucking is usually harmless in toddlers, it can contribute to a lisp by pushing the teeth out of position. If the child continues sucking his thumb after the age of four, stop the habit by substituting a favorite activity of the child's, one that uses both hands. Telling the child to stop or pulling the thumb out of his mouth is less likely to be effective than positive reinforcement, or rewarding the child when he stops on his own.

Consider using oral motor exercises. Oral motor exercises are sometimes recommended for toddlers to help develop speech, but for ordinary circumstances research shows that they are not effective. However, it is possible that a lisping child may benefit from better mouth musculature, and the relevant exercises are simple and harmless: give the child a straw for her drinks, and encourage her to play with toys that involve blowing, like toy horns or bubbles.

Talk to a doctor about "tongue tie." People with "tongue tie," or ankyloglossia, are born with a short attachment, or frenulum, between the tongue and the base of the mouth, or an attachment too close to the tip of the tongue. If the child has trouble licking his lips, or sticking his tongue out, this short attachment may be the cause of the lisp. This does not necessarily mean the child needs surgery, but a doctor may recommend it in some cases. The surgery, called frenectomy, takes a few minutes at most, and typically results in no side effects other than a sore mouth.

Follow tongue surgery with tongue exercises. If the doctor does recommend tongue surgery and the child's guardians decide to go through with it, make sure to follow the surgery with tongue exercises. These will strengthen the tongue, help prevent speech problems, and prevent the frenulum from reattaching, which can happen in some versions of the surgery. If the baby is still breastfeeding, her doctor will likely recommend that you gently stretch the baby's tongue yourself, after cleaning your hands. For anyone older than breastfeeding age, follow the advice of the surgeon and the speech therapist.

What to Expect From Speech Therapy/Pathology

Expect to make regular, weekly appointments until the lisp is cured. Speech pathology is not an instant fix. Great speech-language pathologists (SLPs) will work with you or your child to help develop great speaking habits and tricks. The more you can meet, the faster you will get rid of your lisp. Sessions are usually between 20 minutes and an hour. Some clinics offer group therapy, easing the pressure on you to perform.

Be prepared to talk about your medical and speech history, or your child's. You need to know the causes of the lisp to find solutions. While some people are born with lisps, some speech problems are rooted in medical history, sometimes going back to birth. Bring a copy of medical records with you. A good professional leaves no stone unturned. Parents are instrumental in helping their children beat a lisp -- expect the therapist to enlist your help.

Expect to be screened and assessed, which is usually just a short conversation or set of word tests. In order to determine the next course of action, the SLP will want to hear your speak. This generally consists of simple questions or repeated words. You may even do an Oral Motor Exam, which is a series of exercises to see how your mouth moves independently of speaking. If you've brought your child in, the SLP may want to observe them playing, with other kids, or with you. Seeing them speak naturally, and not under pressure, is important. You may have your speech recorded for learning and practice.

Prepare for hands-on practice sessions with your SLP. Once the issues are diagnosed, it's time to fix them. This usually consists of copy-catting. The therapist will say a word, and you'll work on copying the physical movements -- mouth, tongue, and breath. You may be given a mirror to help you watch your mouth's movements.

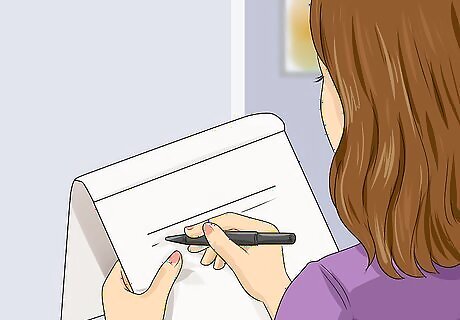

Expect to get homework. Many of these exercises can, and should be, practiced at home. Expect to get a series of handouts helping you work on the lisp later on.

Expect to work for several weeks, not to be fixed instantly. Know that you will keep developing new strategies for as long as it takes. Don't get discouraged if he/she says it may take a few weeks or months. Once you've got the skills down to get rid of a lisp, they rarely ever leave you again. Everyone is different -- some might have weekly sessions for a month, others may need a year or more. Ask for exercises or ways to practice at home if you're dissatisfied with your progress.

Comments

0 comment