views

X

Research source

If your situation is relatively straightforward, you can draft your own last will and testament and avoid attorney fees.

Writing Your Will

Decide how you will write your will. You have a few options here: Write your own will. Once you know your state's requirements, decide how you plan to fulfill them. You can write your own will and be responsible for making sure it fulfills your state's requirements. Be aware that state laws can change from year to year, so the process may be more complicated than you think. Hire an attorney. An attorney can review the will you write, provide you with witnesses and ensure that you have met your state's requirements. This can be a costly option depending on your attorney’s fees and how complicated your will is. Wills that “unnaturally dispose” of the testator’s assets should always be overseen by an attorney. Unnatural disposition includes cutting your family out of the will, giving all of your assets to someone that is not in your family if you have living family members and giving your assets to someone that you have not known for very long. Use an online will writing service. This type of service will automatically ensure that your will is written according to your state's requirements. Online will writing services generally cost between $60 and $100, depending on how complicated your will is.

Identify yourself on the will. Include identifying factors in your will to ensure that your will isn’t confused with that of someone else with the same name. Identify yourself by name, Social Security number, and address. If you don't have a Social Security number, provide a different form of ID, such as a driver's license or state issued ID number. You may also include your date of birth to further identify yourself.

Make a declaration. Introduce the document as your last will and testament as the first sentence of your will. In the full declaration that follows, you need to state clearly that you are of sound mental health and of contractual capacity, and that this will expresses your last wishes. Without this important step, it could be argued that your will is not legally viable. Use this statement: “I declare that this is my last will and testament.”

Include a provision nullifying all previous wills. This type of provision will ensure that any previous wills that you may have written are no longer valid. Use this statement: “I hereby revoke, annul and cancel all wills and codicils previously made by me, either jointly or severally.”

Include information attesting to your soundness of mind. Because wills can be challenged if the testator of the will was not of sound mind (that is, the testator was suffering from dementia or another ailment that prevented him/her from understanding the effects of a will), the testator should include information in the will that proves the testator’s soundness of mind. Include this statement: “I declare that I am of legal age to make this will, and that I am sound of mind.” In addition to including the above text in the will, you may want to videotape the execution of the will to put to rest any future allegations of incapacity.

Attest that your wishes do not result from undue influence. The disposition of assets in your will must be according to your wishes, and can't be the result of any type of outside influence. If you think that your will could be subject to a challenge of undue influence, contact an attorney who can help you protect the will from the challenge. Include this statement: “This last will expresses my wishes without undue influence or duress.”

Include family details. If you're leaving part of your estate to a spouse, children or other family members, they should be named as such in your will. Include the following lines, if appropriate: ”I am married to [spouse's first and last name], hereafter referred to as my spouse.” ”I have the following children: [list children's first and last names as well as their dates of birth].”

State your appointment of an executor. This person will ensure that your will is followed. The Executor is known in some states as a “personal representative.” You may also want to name a secondary executor if the first is unable to perform the duties at the time of your death. The executor is the person who distributes assets and property according to your will. Because executors are so frequently asked to handle assets in a professional manner, you should ideally select an individual with a background in business or law. Increasingly, individuals are selecting professionals -- usually lawyers -- to deal with these matters rather than leaving them for a member of an already grieving family. For example: “I hereby nominate, constitute and appoint [executor's first and last name] as Executor. If this Executor is unable or unwilling to serve, then I appoint [backup executor's first and last name] as alternate Executor.” Determine if your executor should post bond. If the executor must post a bond, this will protect against fraudulent use of your estate. However, requiring the executor to post a bond can be expensive for the executor, depending on the size of your estate, and could prevent your chosen executor from serving.

Empower the executor. Authorize the executor to act in your interest regarding your estate, debts, funeral expenses and other items. Write clauses empowering the executor to do the following: Sell any real estate in which you may own an interest at the time of your death and to pledge it, lease it mortgage it or otherwise deal with your real estate as you yourself would do. Pay all of your just debts, funeral expenses, taxes and estate administration expenses. This allows your heirs to take their shares without later deductions or complications. State if your executor should post bond or serve without bond. If your executor must post a bond, the beneficiaries to the will are protected and insured if the executor fails to carry out the distribution as the will stipulates. However, requiring the executor to post a bond can be expensive for the executor, depending on the size of your estate, and could prevent your chosen executor from serving.

Bequeathing Your Assets

Determine the assets you can legally bequeath. You may not actually be able to distribute all of your assets as you see fit, based on certain state laws and prior legal arrangements. You should consider previous legal contracts you have entered, and whether you live in a common law or community property state. In common law states, anything with only your name on the deed, registration papers or other title documentation is yours to bequeath. In community property states, 50 percent of all accumulations during a marriage legally belong to a spouse, and a will can't supersede that. There are nine community property states: Arizona, California, Idaho, Louisiana, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, Washington and Wisconsin. Alaska also allows couple to opt into a community property system if the couple so chooses. Other legal documents, such as pre-nuptial or ante-nuptial agreements and living trusts, can also affect what you can legally bequeath in your will. Examine any previous legal documents and the laws in your state to determine if they affect how you can distribute your assets.

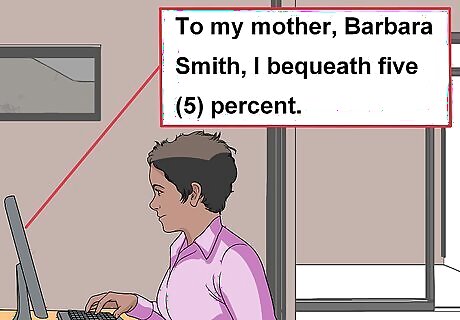

State the division of your assets. State the way in which your assets will be divided among people using percentages, which should add up to 100 percent. For example, one line might read: To my mother, Barbara Smith, I bequeath five (5) percent. Wills that “unnaturally dispose” of the testator’s assets should always be overseen by an attorney. Unnatural disposition includes cutting your family out of the will, giving all of your assets to someone that is not in your family if you have living family members and giving your assets to someone that you have not known for very long.

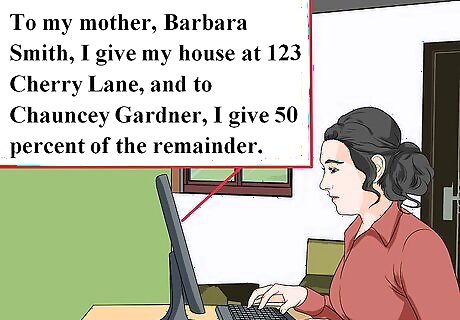

Specify distribution of particular assets. If you want a beneficiary to receive a specific asset, you may state that as well. Then that particular asset will not be included in the percentages of your estate (the remainder) that is divided among other beneficiaries. For example, one line may read: “To Barbara Smith, I give my house at 123 Cherry Lane, and to Chauncey Gardner, I give 50 percent of the remainder.” Make sure that you are as specific as possible with your disposition. Include any addresses of real estate, descriptions of any personal property and full names of beneficiaries.

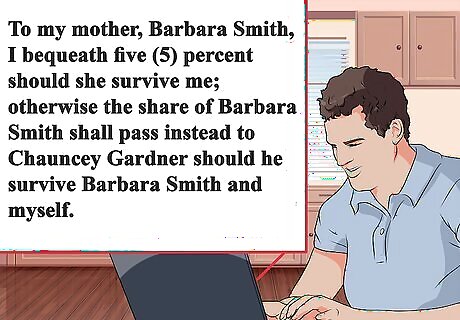

Include provisions for beneficiaries dying before you. Include statements that clearly explain who gets a beneficiary's gift if that person dies before you. For example: “To my mother, Barbara Smith, I bequeath five (5) percent should she survive me; otherwise the share of Barbara Smith shall pass instead to Chauncey Gardner should he survive Barbara Smith and myself.” If you want a deceased beneficiary's gift to just go back into the pot and be divided among your living beneficiaries in shares proportionate to what you provided for them, you can use conditional language such as: “To my mother, Barbara Smith, I bequeath five (5) percent should she survive me.” If you do not name an alternate to specifically receive Barbara's gift, her gift will "lapse" and go back into the pot.

Designate a guardian to minor children. Your will should designate who will serve as the guardian to any minor children, if applicable, in the event of your death.

Allocate conditional gifts. You can also include conditional gifts in your will that are contingent upon something. For example: you can condition a gift on the beneficiary graduating from college, but you can't condition a gift on the beneficiary marrying a certain person that you want him/her to marry. If the conditions specified as a prerequisite to receiving the gift are against any other laws, the court will not enforce them.

Make special requests. You may choose to stipulate how your remains should be handled, where you will be buried, and how your funeral will be paid for. For example: “I direct that on my death my remains shall … ”

Finalizing Your Will

Sign the will. Conclude the document with your signature, name, date and location. Follow your state’s requirements on signing. How you sign the will is a matter of state law and can affect its validity. Initial or sign each page of your will, per your state’s requirements. Do not add any text after your signature. In many states, anything added below the signature will not be included as a part of the will.

Sign your will in the presence of one or more witnesses. In many cases, the will must be signed in the presence of two witnesses, who then sign a statement asserting that you are of legal age and sound mind and that you signed your will in their presence. Each state has different requirements for what constitutes a legal last will and testament. The differences in requirements primarily pertain to relatively small issues in execution, such as how many witnesses are required and when those witnesses are required to swear to or sign the will or matters of notarization. Here are a few examples: In Illinois, a will must be signed by the testator and two witnesses. The witnesses should not be beneficiaries of the will. No notarization is required. In Kentucky, wills require only the signature of witnesses if the will itself has not been "wholly" handwritten by the testator. In these cases, the witnesses and testator must all be present together and bear witness to all signatures. In Colorado, there is more than one way to make a valid will. You can have two witnesses sign, but they can do so at any time up to the execution of the will, as long as they attest to witnessing the testator sign the will or they claim to have received acknowledgement of the will from the testator before his/her death. Alternatively, the will can be signed and authorized in front of a notary, in which case no further witnesses are required. Or, as a third alternative, handwritten wills can be acknowledged by a court without need for witnesses or notarization.

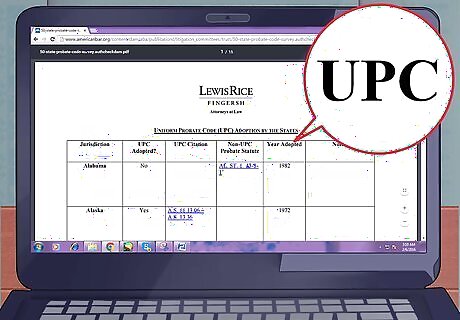

Find out whether your state adopted the Uniform Probate Code (UPC). The UPC is an act drafted by the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws to standardize state laws governing wills and other matters related to estates. It has been adopted in full by 17 states and in part by many other states. To find out whether your state adopted the UPC, check with the American Bar Association. If your will does not meet the legal requirements, it will be found invalid and any property will pass under state laws governing the distribution of assets when someone does not have a will.

Figure out how your state handles property allocation. States differ in terms of what to do if a person mentioned in your will dies before you. Check with the American Bar Association to find out specifics for your state. link. In some states, if you do not change your will to account for the death of a beneficiary, the property that was supposed to go to the beneficiary automatically passes to the beneficiary’s heirs. In other states the beneficiary’s heirs do not recover the property, which is combined with the rest of the estate and distributed among the living beneficiaries. For example, if you leave your house to your sister and she dies before you, the house could go to her children. Another scenario would be that, when you die, the value of the course could be split among the still living beneficiaries.

Making Changes to Your Will

Do not alter the will after it has been signed. The witnesses to your will testified to your capacity and acknowledged your decisions, but their signatures are invalid if the document is altered after the fact.

Revisit your will if your assets change. If your assets change after you write the will, you should edit the will to include these changes, or execute a new will.

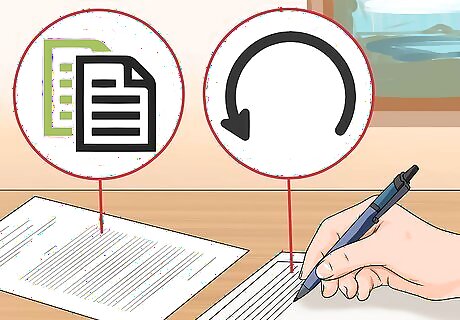

Make modest changes with a codicil. If you need to make minor changes, use a "codicil." This is a separate document that explicitly refers to the original will and serves as a minor amendment rather than a replacement to the original will.

Make substantial changes with a new will. Substantial changes should be made via a new will. It is not uncommon to replace a will if the first will is made at in early age. Your children will grow; you may divorce and remarry; or your financial situation could change drastically -- any of which would require such substantial changes that only a new will is appropriate.

Storing Your Will

Store the will safely. Your will is not filed with the courts until after your death. If the will is destroyed, it can't be filed. Make sure that you store the will somewhere that can be found after your death. Consider storing your will in a safe at your home or in a safety deposit box at your bank. Many people give their wills to an attorney for safekeeping, or tell their named executor where the will is located.

Give a copy to your executor. Consider handing over a copy of your will to your executor in case something happens to the original.

Make a note to yourself. It’s a good idea to make a note to yourself to say where your will is stored. In the event that you forget where your will is stored, you will be able to tell your executor, spouse or other party.

Comments

0 comment