views

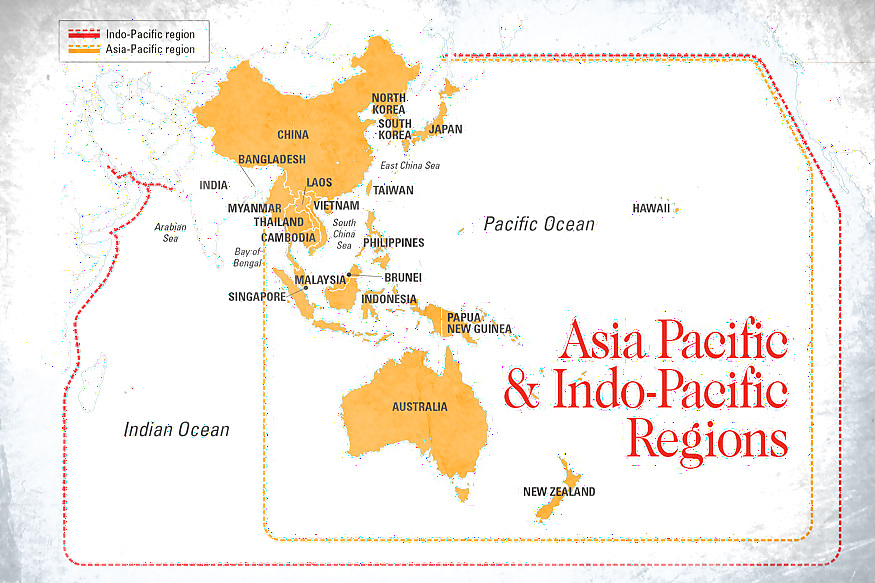

“What’s in a name? A rose by any other name smells just the same”, Shakespeare had written so beautifully many centuries ago. In diplomacy, a name can mean a lot of things. Any change of constructs and terminologies are thought through for many years before being implemented. Which is why America’s recent use of the phrase “Indo-Pacific” as opposed to “Asia Pacific” carries a lot of meaning and import for India.

It was first brought up by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in 2007 in a speech to the Indian Parliament to represent the vast swathe of water that connects the Pacific and the Indian Oceans. At that time, there were not too many takers for it even in the India foreign policy establishment.

It has recently got some traction after Rex Tillerson, the US Secretary of State, used it in a major policy speech in Washington. Trump in his visit to China also referred to the Indo-Pacific. His NSA McMaster is also using it. The White House has not referred to ‘Asia Pacific’ even once in Trump’s first visit to Asia since taking office. Neither has it offered an explanation for the use of this new phrase ‘Indo-Pacific’ as opposed to ‘Asia Pacific’.

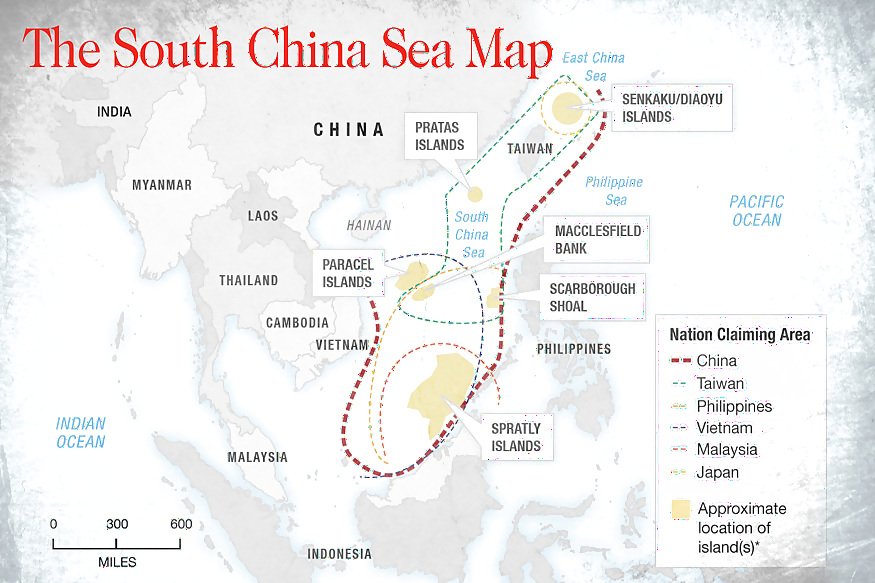

Why is the use of this phrase important? One, it diminishes the hold of China in this vast swathe of water. When Chinese diplomats refer to disputes in the South or East China Seas, it gives an impression to the layman that these are China’s seas. That China has first rights over these waters. And whatever disputes arise therein are brought forth by countries that want to challenge China’s writ in these waters. The reality is actually the opposite. It is China that is trying to impose its writ in these waters, thereby trying to create a new Chinese order.

America’s phenomenal success from the end of the Second World War until now was underwritten by the American order on either of its flanks. No country was powerful enough to challenge America either on the Atlantic or on the Pacific. This implicit peace meant seventy years of extraordinary growth, the kind of which has been unparalleled in human history for such a brief period of time.

Similarly, the Chinese realize that if they want to claim the 21st century as their own, then they need to build a “Chinese order” in the waters of the East and South China seas. Which is why the Chinese raked up a 19th century concept of the ‘nine dash line’ to give legitimacy to its claims in the South China Sea. China did this in Doklam too, dishing out a British era agreement to lend legitimacy to its claim on this disputed piece of land.

Now if the whole world, including America, is going to refer to this part of the world as the Indo-Pacific, it gives less legitimacy to China’s hegemon in this region. What is also does is give India greater impetus in these waters given the centrality of India in the Indo-Pacific.

India has long been wanting to play a greater role in these waters. India has always believed it was the net security provider in the Indian Ocean region. China’s growing tentacles in Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Myanmar’s coasts has been a matter of grave concern for India for it challenges this very notion.

In much the same way if countries in Asia all the way from Japan to South Korea to South East Asia are going to refer to the Indo-Pacific it implies a greater primacy for India in these often-times choppy waters. Whereas the term Asia Pacific means China is very much central to its construct.

The Chinese loved the idea of the Centre. China is called Zhong-guo in Chinese meaning “Middle Kingdom”. In Indo-Pacific, India is central, not China.

But this can also cut both ways. The Chinese can use this new construct of ‘Indo-Pacific’ to legitimize their own growing presence in the Indian Ocean Region. This is a danger that India needs to guard against. Through One Belt, One Road China has already established deep physical connections in countries of the Indian Ocean Region. China being a player in the Indo-Pacific gives them a new terminology to justify OBOR.

Comments

0 comment