views

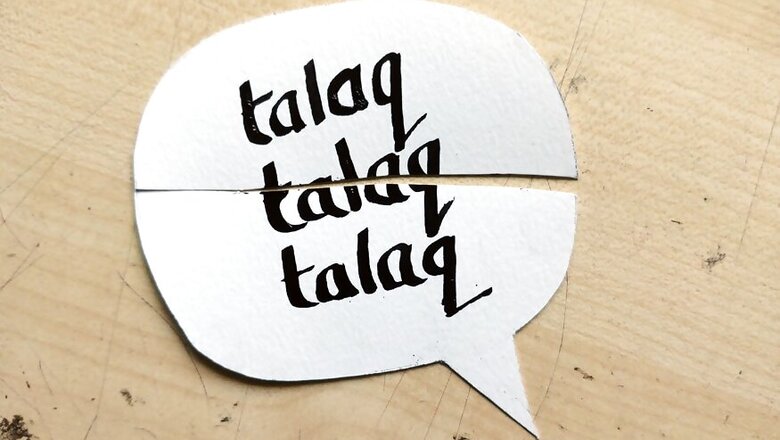

New Delhi: Those who may think that the events around Triple talaq – from Supreme Court judgments to the debates in Parliament to the draft of instant Triple Talaq Bill – are slowing chipping away personal laws and ushering in a Uniform Civil Code are mistaken, SC lawyer and Congress leader Salman Khurshid has argued in his latest book.

Titled, ‘Triple Talaq: Examining Faith’, Khurshid tries to explain how developments around the, now infamous, Islamic mode of divorce in no way suggests a need for bigger ‘reform’ in the religion.

“Ultimately, the court will have to decide if equality is uniformity or diversity too is desirable. Triple talaq was obviously not a deserving test for that proposition because of its inherent odious nature and its questionable pedigree,” Khurshid says in his book.

The author also argues that organic changes within the Islamic society in India were already there to be seen. “Although polygamy remains lawful (subject, of course, to strict conditions), government regulations prohibiting polygamy for civil servants has been quietly accepted by Muslims. Similarly, restrictions on cow slaughter have been widely accepted across the country,” writes Khurshid.

‘Triple Talaq: Examining Faith’, published by Oxford University Press, contains anecdotes from the Supreme Court, where he was appointed amicus curiae, and his own arguments in the case.

Talking about his book to a news portal, Khurshid explained the reasons for writing it —

“It was a matter of interest to quite a few. People had imagined it to be something that it wasn’t... I am not advocating Triple Talaq, I’m against it but only to the extent that it’s not a valid form of divorce... The attempt to demonise the community because they have a somewhat unacceptable kind of divorce... that has to be put in the right perspective.”

To give a glimpse about the arguments made on the issue, whose popularity can be gauged from how it spilled over from courtrooms onto the streets and poll campaigns, here is an excerpt of Khurshid’s book, a pre-release copy of which News18 has accessed:

Many votaries of the Uniform Civil Code see it [Triple Talaaq judgment] as clearing the path for what one channel called ‘One Nation, One Law’. But have they purposely overlooked the majority of three Justices giving a clear verdict on protection of Personal Law? A Uniform Civil Code, although mandated by the Directive Principles of State Policy, would still need to pass muster as far as the chapter on Fundamental Rights is concerned.

The recent unanimous pronouncement of a Constitutional Bench of nine judges has rearranged the landscape somewhat dramatically and finally laid to rest any doubts about the stand-alone nature of Fundamental Rights and making Article 21 the ultimate repository of rights that people have; indeed, even going further to hold that some rights can be traced to pre-constitutional natural rights. Jurisprudence on Fundamental Rights is a seamless whole and any dent to any part of it will inevitably impact the rest.

We made a mistake on civil liberty in the early years of our Independence by subjugating individual rights to the welfare of society in a utilitarian calculus.

The result was the Fundamental Rights judgment of the Emergency period that most of the present votaries of the Uniform Civil Code deprecate and indeed, was regretted in later life by the Justices who pronounced it.

Furthermore, Justice Nariman’s observation on Nikah should be a warning that the Uniform Code will certainly not be a majoritarian version of what is desirable.

For instance, not one person has ever ventured to explore whether a Uniform Code will require that all funerals culminate in a similar manner, that is, would everyone be cremated, buried, or confined to the Towers of Silence?

Furthermore, under the marriage 151 provisions, would same-sex marriages be permitted as they now are in a growing number of countries across the globe?

The judgment certainly gives clues to what might be the final outcome of pending proceedings in the Section 377 Naz Foundation matter, but that would go only to the extent of decriminalization of same-sex consensual relationships.

Modernism might not be as simple as some people make it out to be in order to promote petty political aspirations. The misplaced belief that modernizing community law is essentially a matter of reviewing different religious practices from the point of view of a version assumed to be superior is destructive to the notion of diversity that is a cornerstone of our democracy. Besides the philosophical dimension, there is also the political reality of diverse sub-cultures.

How much of tribal culture should be preserved in the face of modernity is far from a settled question of our democracy. Modes of marriage vary vastly in different parts of the country, particularly with matriarchal societies in certain parts. It might be possible to let a universal idea of equality prevail in the matter of genders by a degree of interference with existing systems, but then where would one draw a line of balance?

People who question the right of human beings to sacrifice animals for religious reasons (because they are vegetarians or subscribe to non-violence as a matter of faith) might end up having to question bali for Hindu Goddesses as much as the qurbani rituals of Muslims.

An interesting point was raised in a tweet by my erudite colleague, Shri P Chidambaram, after the judgment was delivered. He tweeted that only triple talaq (meaning the instant talaq) has been declared unlawful and that other 152 forms of talaq remain to be considered, being equally unilateral.

The Attorney General had made similar arguments during the hearing. Then again, another colleague has been reported to have opined that Parliament still has a role to play to implement the judgment. These raise much wider questions far beyond triple talaq.

Even the Supreme Court did not envisage going that far and simply indicated that nikah halala and polygamy would be considered by another bench in due course. As to why the concept of talaq does not suffer from the mischief of triple talaq, the answer is to be found in the remarkably erudite exposition of Shariah by the then Chief Justice.

As far as the intervention of Parliament is concerned, it is surprising that a matter that the majority of the Supreme Court steered clear of—not because it found it expedient and appropriate, but because it did not see the jurisprudential ground for passing the buck to Parliament — should be assumed by some persons as a signal to Parliament to proceed.

Thus any attempt by Parliament to venture into this area will inevitably come back to the Supreme Court, where a later generation of judges will have to look for guidance in the present judgment of the Constitutional Bench. Hopefully, the myopic concession of the Board, that although the court cannot interfere in the matter yet Parliament can legislate to obliterate a 1,400-year-old matter of faith will not restrict their options.

Ultimately, the court will have to decide if equality is uniformity or diversity too is desirable. Triple talaq was obviously not a deserving test for that proposition because of its inherent odious nature and its questionable pedigree.

It is, indeed, important that we retain a rational perspective on the entire affair, keeping our sights focused on the then Chief Justice’s beacon—that rationality and faith cannot be tested against each other but must instead be kept in a careful balance in our society.

Barely days after the Supreme Court judgment came the verdict in the prolonged trial of Baba Gurmeet Ram Rahim of Dera Sacha Sauda. The mayhem that was unleashed by his devotees, as indeed the dark stories that came tumbling out in the media, were a sharp reminder that the rule of law, based essentially on reason, has great challenges in the hysteria of the faithful.

The age of reason still has a long way to go before it can be said to be universally accepted in our land where the cults of modern-day demi-gods continue to spread their tentacles and political leaders, too, are generously borrowing from their style and substance. Morality seems under threat from a combination of a return to the past and rushing towards postmodern, permissive social mores.

For people who believe that India’s problems arise from the backward mentality of its Muslim population (as though Pakistan does not have any problems!), the Not For Commercial Use triple talaq 154 judgment came as a vindication of their unsuccessful battle in Shah Bano some thirty years ago.

It is interesting that the Board, as indeed Muslim scholars, seldom attempt to explain that Islam is followed in India in a unique manner, in that the criminal dimension of Shariah has never been applied and many practices are made subject to the general law of the land without any protest from Muslims. Although polygamy remains lawful (subject, of course, to strict conditions), government regulations prohibiting polygamy for civil servants has quietly been accepted by Muslims.

Similarly, restrictions on cow slaughter have been widely accepted across the country. It is another matter that the Supreme Court has not upheld the ban on the footing of faith and made strenuous efforts to justify it on the Directive Principles ground of agriculture. Furthermore, in interpreting or applying Shariah, there has been little inclination to open the Pandora‘s box of conflict of laws given that the four schools of Shariah differ on important aspects, as indeed Hanafi and Maliki do on triple talaq. It seems that there are no rules to decide whether the rule of reason to be applied in the case of parties of different schools would weigh in favour of the maslaq of the plaintiff or the defendant. The Muslim Marriage Dissolution Act, 1939 attempted such an exercise.

Comments

0 comment