views

The auction of commercial coal blocks in India is scheduled to start on June 18. However, no list of the coal blocks to go under the hammer is out yet. Jharkhand chief minister Hemant Soren has sought a moratorium of at least six months on the move, saying a lot of domestic and foreign companies would not be able to participate in the process because of the Covid-19 crisis and related travel restrictions.

A voluntary organisation, Chhattisgarh Bachao Aandolan, campaigning against mining in the Hasdeo river forest area has demanded that no coal block which has been classified as no-go because of dense forest cover should be put up for auction. In the case of Chhattisgarh, the catchment of a major dam is at stake which could put water security of the state at risk in the long run, environmentalists say. The opencast mining as proposed in almost every block of the area could not only wipe out 50% of the forest but also advance the silting speed of the dam, minimising its live storage capacity year by year, they say.

In the 1970s, the present state of Chhattisgarh was still part of Madhya Pradesh. A minimal 10% area was under irrigation and entirely dependent on rain-fed agriculture. The present districts of Janjgir and Raigarh used to have massive migration of labourers in the non-kharif season to other states, especially Uttar Pradesh, Haryana and Bihar in brick kilns. Around the same time, the Korba area was identified as a major centre for coal mining and power generation, and for that too the requirement of water was a major concern, besides the abundantly available coal.

A multipurpose dam project was envisaged by the then Madhya Pradesh government near the Hasdeo river which is the main tributary of the Mahanadi, apart from the Shivnath river.

The upstream dam on Hasdeo was planned around 30 km north of Korba with the help of World Bank financing. By the early 1990s, the main dam was built and named after a Dalit Leader as the Minimata Bango Reservoir. The area which was submerged in the dam was huge. A total of 61 tribal hamlets and around 11,000 hectare of good forest area was sacrificed to create this reservoir, which has a planned live capacity of 3,045 million cubic metre. It had been reduced to 2,894 million cubic metre by 2013 due to silting, as per a Central Water Commission assessment.

A total of 2.55 lakh hectare of land was identified to receive double-crop irrigation and in subsequent years the canal system was developed which provided water to the fields on large tracts of land, bringing prosperity to the region, especially in the Dalit and other backward classes (OBC) living in the area. The displaced population of the submerged area, mostly tribals, never get proper rehabilitation and settled in the nearby forested areas mainly north of the reservoir. The dam also envisage 441 million cubic metre of water for industrial use, mainly power generation which now is around 12,000 MW.

During 2004-09 when many identified coal blocks of the country were allotted to certain private and government companies, around 20 of these blocks from the Hasdeo river area, known as Hasdeo Arand Coal Fields in ministry of coal parlance, were also on the list. The Hasdeo Arand Forest is the main catchment of the Hasdeo river and the Bango dam is entirely dependent on this water supply, yet the allotment was made without considering the water security of the region besides the huge cost on environment. Similar allotments were also made in some other dense forested areas of the country, affecting the catchment of some other rivers.

At this point, the ministry of environment and forest and the ministry of coal agreed on a mechanism to save pristine forest areas from mining and allow mining in the rest of the areas. The study conducted is known as the 'go/no-go study' of coal blocks, and in the first round in which 9 coal fields of the country were examined, 396 coal blocks out of 602 surveyed were categorised as go areas where mining can be done. The ministry of coal found that no-go blocks numbered at 206, a highfigure, so it sought the intervention of the Prime Minister’s Office for relaxing the norm of the classification of the blocks for mining. The PMO appointed a committee under member of the Planning Commission BK Chaturvedi which decided that now classification be done by taking crown density of 0.5 as parameter instead of 0.4 earlier and also leaving out fragmented areas as category go areas.

This new identification added 53 more coal blocks in category go, leaving just 153 coal blocks in no-go category. The chairman of the committee, BK Chaturvedi, also endorsed the classification and recommended this to be adopted as criteria for clearance of the mining proposal. The Hasdeo Arand Coal Field entirely falls in this no-go area, confirming its importance as catchment and its environmental value.

However, coal ministry was not happy with this as there was also displeasure among allottees whose coal blocks were found to be in the no-go category. The MoEF contested the stand of ministry of coal by a strong note submitted to the cabinet committee of infrastructure in which it was said that coal blocks identified as no-go constitute a very small area of India's coal deposits and it's less than 15% of the Indian coal bearing areas. The remaining 85% can fulfill future demand easily. Thus, there was no need to mine coal in dense forests.

But the list of affected companies included both private and government ones and it led to dumping of this scientific and rational classification achieved after balancing the needs of sustainable development. The government of India decided in 2012 that a new study for finding violate and inviolate areas be done and for deciding the parameters of the study a committee was formed. The committee gave its report in 2014, but till date no action has been taken on the recommendations of that report and the entire classification has been dumped.

In 2014, the Supreme Court of India gave its famous judgment in the coal scam matter and cancelled all the coal block allotments made earlier, thus providing a clean slate to the government of India to write afresh its coal story. The government, rectifying its earlier mistakes on the allotment front, enacted the Coal Mines Special Provisions Act 2015 to implement the judgment. This new law provides a mechanism of direct allotment to government companies and a system of public auction for allotment of coal blocks to private companies. However, this new law does not create any bar for identifying the coal blocks for allotment on environmental values.

In February 2015, when the allotment/auction process was going on, leading advocate Prashant Bhushan wrote to the-then coal secretary Anil Swaroop to spare densely forested coal blocks from the allotment process. The media has always reported how many coal blocks or deposits got stuck due to the no-go policy, but it has never been reported how much coal deposit or coal blocks are available for exploitation.

INDIA HAS ENOUGH COAL DEPOSITS OUTSIDE NO-GO AREAS

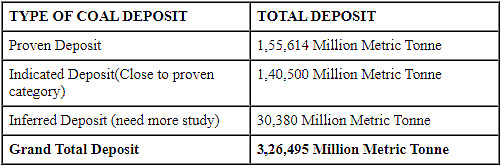

The total coal deposits in India are found in about 25 medium and major coal fields. Present production in India is around 700 million metric tonnes per annum (MMTA), with around 150 MMTA import,which includes import of coking coal that is not available much in the country. Projected demand of 1,500 MMTA by 2030 requires some 45,000 million tonne coal deposit for the next 30 years. For the next 50 years, this would be 1,00,000 million tonne if demand would be 2,000 MMTA. Considering this, the presently proven deposit of 1.55 lakh million tonne is more than enough.

The cabinet note submitted by the MoEF in 2011 was strongly averse to the idea of allowing coal mining in densely forested areas classified as no-go and argued that these deposits are barely 15% of the total deposit and there was no need for opening up the said areas. The present position of Indian coal deposits according to available data is:

Despite the position being thus, the ministry of coal is not sparing the coal blocks situated in the dense forested areas from allotment or auction process. In the last five years, it has allotted Parsa, Madanpur South, Kente Extension, Paturia and Gidhmuri, all of Hasdeo Arand Forest, to various government companies. Needless to say that all these blocks were classified as no-go in 2010 and subsequently inviolate by the Forest Survey of India while the exercise is still incomplete.

The pledge given under the global climate change deal as well as the country’s push towards solar energy adoption also warrants that while mining coal at least those areas which are densely forested should be spared as forests are the major sink for carbon dioxide. It is true that coal will remain the mainstay in the near future for India’s energy needs, constituting around 60% generation. However, we can certainly and easily fulfill this demand without touching any coal blocks situated in densely forested areas.

The push for mining in these areas are being made under vested interests as the mining cost would be lower or other infrastructure is available in the area. But in this analysis, the environmental cost and water security aspect has not been added, otherwise no prudent person would support mining in these areas. Hope that some good sense prevails in the policy and decision makers and they avoid this planned disaster.

Comments

0 comment