views

On August 26, 1964, The New York Times, on page 9, ran a small story about the test run of a new 12-car train conducted on August 25 in Japan: “It sped 320 miles from Tokyo to Osaka in 3 hours and 56 minutes.” The New York Times aptly captured the mood in Japan that day: “The trip of the Hikari marked a proud day for Japan. Thousands lined the route to wave and cheer as the express flashed past. Traffic was stopped on many main highways as the Hikari approached. The Japan Broadcasting Corporation had a large crew aboard the train, at vantage points along the route, and in aircraft overhead to provide exhaustive coverage of the trip that the Japanese hope will open a new epoch in railroading.”

Indeed, the new railway not only revolutionised the future of railroading but also reimagined the contours of urbanisation in Japan.

Talking about the speed of the new railroad system, Reisuke Ishida, President of Japanese National Railways, said in an interview aboard the train: “We know we can run very safely even at 250 kilometres (156 miles) an hour, but the maximum will be held to 210 on our regularly scheduled runs.”

This epoch-making moment would bring to the world what the Japanese fondly call the “Dream Limited Super-Express,” which heralded the era of high-speed railways globally. It reimagined, reshaped, and revolutionised the mobility landscape by fundamentally altering the past, offering an alternative to aviation, fast-tracking the promotion of economic growth, bringing new urbanisation to Japan, drastically reducing travel times, and ushering in the era of a greener mobility option.

A Familiar Story

The birth of Japan’s Shinkansen was mired in controversy. When the initial plan emerged in the 1950s, it faced fierce opposition. Many deemed it unnecessary, predicting it would become a white elephant. Others pointed to the declining popularity of rail travel in the United States, where highways and air travel were ascendant, arguing that Japan would soon follow suit.

This initial hostility in Japan towards what would soon be known as the “bullet train” mirrors a familiar narrative that has unfolded over the past decade concerning the development of a high-speed railway in India with Japanese assistance between Ahmedabad and Mumbai.

The Legacy – Dangan Ressha

The ambitious goal of completing the Tokaido Shinkansen project in a remarkably short five-and-a-half years owes much to the legacy of wartime Japan. The initial concept, dangan ressha (bullet train), emerged in 1939 with the aim of connecting Tokyo and Shimonoseki in western Japan via a nine-hour rail service. This ambitious plan envisioned dedicated high-speed corridors for passengers and freight, necessitating a switch to wide-gauge rails – like those in Europe and America – from the traditional Japanese narrow gauge (1067 mm). The government even acquired land and began constructing tracks and tunnels in 1941.

However, fate intervened. The outbreak of World War II and Japan’s subsequent defeat brought the dangan ressha project to a standstill. Two decades later, when the Tokaido Shinkansen plan was revived, the partially built dangan ressha route, including its unfinished tunnels, was incorporated into the new alignment.

Be In Time for the Olympics

The state-run Japanese National Railways (JNR) resumed planning for the Tokaido Shinkansen Line in the 1950s. Shinji Sogo, JNR’s fourth president, championed the idea of a super limited express train in 1955. Alongside Hideo Shima, the chief engineer, Sogo vigorously promoted the bullet train as a “national project.”

They pressed forward with laser focus despite growing doubts. Air travel was on the rise, and automobiles were becoming increasingly common in Japan, mirroring trends in Europe and the United States. Some even speculated that railways had entered a period of terminal decline.

Construction finally commenced in April 1959 on the new 515 km (320-mile) route between Tokyo and Osaka. The plan called for electrified trains capable of reaching 210 kph (130 mph) on a dedicated, wider-gauge track, aligning with American and European standards. This extraordinary feat of engineering and technology was to be completed in just five years, with the Shinkansen unveiled to the world during the 1964 Tokyo Olympics – the first Olympics held in Asia.

The project construction team rallied around the slogan, “Be in time for the Olympics,” and delivered the project “just in time,” despite the scepticism of many JNR employees regarding the likelihood of completing the project within such a record time.

Drummed out

The construction of the first Shinkansen line was not without its drama. Escalating costs led to the unceremonious departure of JNR President Shinji Sogo and Vice President of Engineering Hideo Shima – the very pioneers whose vision had brought the project to life.

The soaring price of land acquisition, coupled with rising material and personnel costs, drove the project’s budget significantly higher. Initially approved by the Japanese cabinet in 1958 at ¥194.8 billion, the cost had to be doubled to ¥380 billion. While an $80 million loan from the World Bank helped cover the increase, Sogo and Shima were ultimately forced to resign.

Despite their absence at the 1964 opening, their legacy remained secure. Upon Shima’s death in 1998, Japan Railway & Transport Review wrote in his obituary: “Although both men were no longer at JNR to see the opening of the Tokaido Shinkansen… their names will always be associated with the shinkansen – Mr Sogo as its political father, and Mr Shima as its technical father.”

An Exemplar Icon is Born

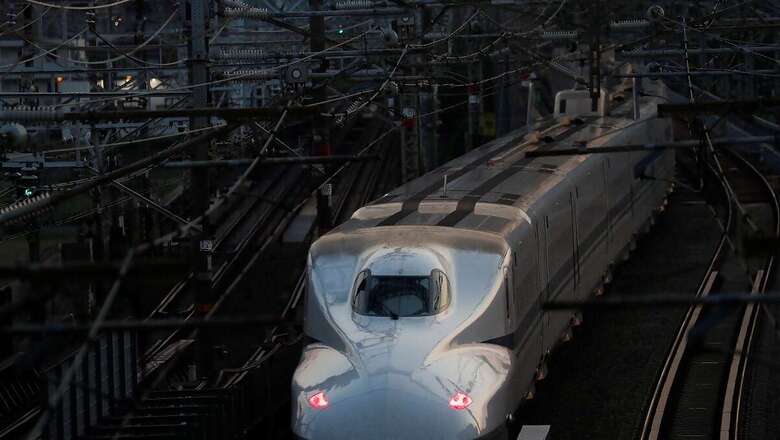

A new wonder of the world, the exemplar icon, generically and officially termed ‘super limited expresses’ (chotokkyu), today best known as the bullet train (dangan ressha) and Shinkansen (meaning “new trunk line,” the dedicated infrastructure built for high-speed services), was born six decades ago this week, precisely at 6 a.m. on October 1, 1964—nine days before the opening of the Tokyo Olympics—when the first commercial Shinkansen train, the ‘Series 0’ Hikari 1, glided out of Platform 19 at Tokyo Station.

Among those present at the launch ceremony was JNR President Reisuke Ishida, who cut the ribbon for the “Hikari No. 1” train as it departed from Tokyo Station while a brass band played a marching song. Simultaneously, the “Hikari No. 2” train left Shin-Osaka Station for Tokyo, completing the four-hour journey and both trains arrived at their respective destinations precisely on schedule at 10:00 a.m.

Once operational, the newly built Shinkansen reduced travel time between Tokyo and Osaka from around seven hours to just four, making day trips between the two cities possible. This development had a profound impact on Japan’s economy and society.

Thus, the world was introduced to the fastest, most advanced, and visually striking train ever seen. Its bullet-shaped nose cone, combined with the distinctive ivory and blue livery, quickly turned it into a design icon and, along with its unprecedented speed, earned it the name ‘bullet train’.

The Shinkansen also heralded Japan’s newfound technological prowess, showcasing a nation that had risen from the devastation and humiliation of World War II. In her book, Dream Super-Express: A Cultural History of the World’s First Bullet Train (2022), Jessamyn Abel, associate professor of Asian studies at Penn State, writes: “The train ended up meaning different things to different people… This was a time when Japan was recovering from World War II, preparing to host the Olympics, and eager to demonstrate its resurgence. The train became a symbol of national pride, showcasing their remarkable comeback to the world.”

High Speed

Since its inaugural operating speed of 210 kph (130 mph), the Shinkansen’s velocity has steadily increased thanks to line improvements and newer rolling stock. Today, with operating speeds exceeding 320 kph (199 mph), the journey between Tokyo and Osaka has been reduced from four hours in 1964 to a mere two hours. The high-speed rail network now spans over 3,000 km, connecting major cities across three key islands.

Seven Minute Miracle

The best airlines often take pride in achieving a 30-minute turnaround time at airports. When it comes to Shinkansen trains, however, the turnaround time is an ultra-efficient 12 minutes. This super-efficiency extends even to the cleaning crew. Once the train arrives at Tokyo or another originating Station, they clean the entire train in just seven minutes, preparing it for the next wave of passengers. It’s a finely-tuned process at terminal stations: the train spends only 12 minutes there—two minutes for passengers to disembark, seven minutes for cleaning and preparing the train, and three minutes for boarding.

Low Maintenance Cost

Beyond its speed, one of the key technological advances the Shinkansen introduced—and which would later be emulated by new high-speed railway lines in Europe and Asia—was the crossing-free Tokaido line. This line extensively used elevated sections and tunnels to maintain consistent levels and minimise curves. Another innovation was the use of island platforms at intermediate stations, which significantly reduced maintenance needs while providing the world’s most extensive and intensive high-speed services.

Several factors contribute to the Shinkansen’s low-cost maintenance system. Its compact design (aerodynamic shape and airtightness allow for smaller tunnels and shorter track distances, also lowering construction costs), concrete rail beds (which, though initially more expensive than gravel beds, have much lower maintenance costs), and lightweight body (which reduces wear on rails and thus maintenance costs). The use of synthetic composite materials also lowers life cycle costs. Additionally, the high operating speed results in greater efficiency, meaning fewer rolling stock are required to transport the same volume.

Over the decades, the Shinkansen system has successfully balanced initial construction costs with long-term maintenance expenses, optimising the total life cycle cost.

Shinkansen Today

The original Tokaido Shinkansen, connecting Tokyo, Nagoya, and Osaka—three of Japan’s largest cities—has become one of the busiest high-speed rail lines in the world. From its initial 515.4 km (320.3 miles) in 1964, the Shinkansen network has expanded to 2,951.3 km (1,833.9 miles). Today, running at speeds exceeding 320 km/h, it connects most major cities on the islands of Honshu, Kyushu, and reaches Hakodate on the northern island of Hokkaido.

Safest of All

Railways worldwide, especially in India, are notorious for frequent fatal accidents resulting in loss of life and serious injuries. An incident-free rail travel is an oxymoron for railway passengers. However, this is not the case with Shinkansen lines. In a country prone to frequent earthquakes, typhoons, and heavy snowfall, over the past 60 years—spanning more than 21,900 days—Shinkansen trains have operated in Japan without a single accident causing serious injury or the death of a passenger.

This stellar safety record is the result of exceptional attention to construction quality and meticulous detail in the operation and maintenance of trains, tracks, and equipment. A key example is the fail-safe earthquake warning system, which has consistently stopped trains immediately in the event of an earthquake.

It is no exaggeration to say that, when it comes to maintaining a spotless record of zero fatal passenger accidents, Japan’s Shinkansen trains have no equal in the world.

On Time, Every Time

Undoubtedly, safety is the defining feature of Shinkansen train operations, but no lesser achievement is its clockwork-perfect punctuality. A great deal contributes to this: cutting-edge hardware, advanced software, high-speed tracks, ATC (Automatic Train Control), automated train scheduling systems, and exemplary training for operating and maintenance staff, all of which have ensured on-time performance every day for over 19,000 days.

The results are astounding—a precise combination of hardware, software and human excellence enables Shinkansen trains to run at incredibly tight intervals of just three minutes without delays, averaging less than one minute of deviation from the schedule.

High in Comfort

Unsurprisingly, Shinkansen’s services provide exceptional comfort for passengers. The train’s tilting mechanism allows it to lean into curves at high speed, while its airtight body ensures an incredibly smooth and quiet ride by minimising vibration. Additionally, the large-bodied cars offer generously sized seats, providing a comfortable experience without compromising the train’s capacity.

Large Capacity

The spacious design of Shinkansen cars also results in a high passenger capacity, with a standard 16-car train capable of carrying over 1,300 passengers. This high capacity has been achieved largely because, from the outset, all facilities on the Shinkansen system were designed exclusively for high-speed train services, without any mixed traffic.

Shaping Densified Urbanisation

The primary goal of the Shinkansen was to connect Japan’s bustling cities and facilitate the flow of people to the capital. It is characterised by high frequency and short distances between stations, attributes that reflect Japan’s high population density and the location of cities along the rail lines. Over the last sixty years, the development of high-speed rail (HSR) in Japan has significantly improved market access and reshaped spatial distribution dynamics, transforming the socio-economic landscape of both urban and rural areas.

Due to its speed and remarkable efficiency, the Shinkansen revolutionised commuting and urbanisation in Japan. The ability to cover 515 km in just over two hours opened up new possibilities for work and leisure, enabling people to live farther from their jobs. It is no surprise, then, that the Tokyo-Nagoya-Osaka service alone has carried 7 billion passengers, according to Japan Central Railway.

With the extension of Shinkansen routes over the decades, the impact on urbanisation and the economy has been profound. Over time, stations themselves have evolved into lifestyle destinations, with offices, malls, shopping arcades, and restaurants redefining the role of railway stations.

Revolutionising the Railroad World

Over the past 60 years, the Shinkansen has done more than just transform Japan from a war-torn nation into a modern, urbanised, and industrialised powerhouse. It has also revolutionised rail travel worldwide, even as the rise of automobiles and aviation threatened to relegate trains to the sidelines.

Seventeen years after the Shinkansen’s début, its influence spurred the development of high-speed rail around the globe. France’s Train à Grande Vitesse (TGV) commenced operations in 1981, followed by Germany’s first-generation Intercity-Express (ICE) in 1991. Today, high-speed rail networks connect major cities in over two dozen countries, primarily across Asia and Europe.

The Most Spectacular

In terms of high-speed rail, China was initially a laggard but has rapidly emerged as a global symbol of speed and excellence, boasting the most spectacular growth in high-speed rail infrastructure worldwide. At the start of the 21st century, China had neither operational high-speed railways nor any under construction. It wasn’t until 2003 that China began building its high-speed network, inaugurating its first line, the Beijing-Tianjin intercity rail, on 1 August 2008, connecting the two cities, approximately 75 miles apart.

Today, the situation is vastly different.

China’s total operational high-speed rail network spans 46,000 km (far exceeding the combined length of all other countries’ networks), linking all cities with populations of 500,000. By 2035, China plans to extend this network to 75,000 km, connecting all cities with populations of 100,000.

Lessons for India

India’s first high-speed railway line, between Mumbai and Ahmedabad, is shorter than the Tokyo-Osaka Shinkansen line opened in 1964. While the latter was completed in five years, India’s project, which began construction in 2017, is unlikely to be completed before 2028.

Meanwhile, India has overtaken China as the world’s most populous country, with a projected population of 1.64 billion by 2050, half of whom will live in cities. With the urban population expected to double in the next twenty years, India needs to learn from both the Shinkansen in Japan and China’s remarkable high-speed rail success story.

The true lesson is that high-speed rail in India is not a fad. It is a survival and growth imperative. A journey which India must fast peddle now.

The author is Multidisciplinary Thought Leader with Action Bias, India Based International Impact Consultant, and keen watcher of changing national and international scenarios. He works as President Advisory Services of Consulting Company BARSYL. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment