views

In Part 1 of this News18 series, we looked at the ethnic character of the conflict in Jammu and Kashmir. In the second part, we explore the management of this conflict with the premise that salience of the Kashmiri ethnic identity is central to both the cause of the problem as well as its solution.

There is a wide variety of international writings on the approaches for resolving ethnic conflicts. John Coakley, in his article, The Resolution of Ethnic Conflict, provides a typology of the principal strategies that are employed for ethnic conflict resolution. These include 'Indigenisation' (grant of unsolicited autonomy), accommodation through power-sharing, forcible assimilation through use of expressions like "one state, one nation, one language", and 'Acculturation' where minority groups do not seek cultural distinctiveness but integration with the dominant community. Harsher strategies include population transfer, boundary alteration and genocide.

Without getting into the moral question, it can be factually stated that each of the strategies listed above has been used by nation-states in the past. However, it does not automatically follow that any nation is free to pursue any strategy. The nature of the political system and the stated political objectives will, to a considerable extent, determine the contours of a strategy for conflict resolution.

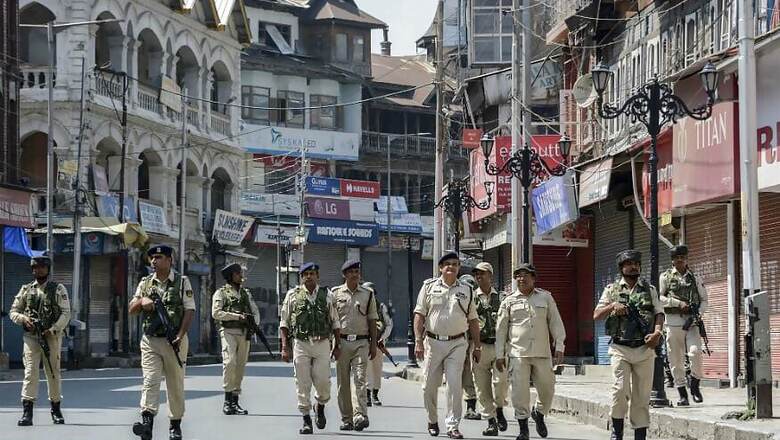

India’s strong democratic roots, a free media (although some chinks have lately started appearing), and an independent judiciary impose limits on strong-arm tactics that can be adopted. It is for this reason that the government will now have to decide a strategy on how to go forward even as restrictions in Kashmir are being eased.

External support from Pakistan needs to be choked off. The government has taken significant steps in this regard and demonstrated a firm resolve in responding to major terror incidents. While we cannot expect immediate results, the pressure on Pakistan is clearly visible. The presence of 300 terrorists in the state, which is the approximate average for the last five years, is not an insurmountable challenge, judging from past successes of the security forces.

What is more difficult to overcome is the lingering suspicion and fear among large sections of people in Kashmir, which is hindering conflict resolution. As Daniel Bar-Tal and Eran Halperin write in their article, Overcoming Psychological Barriers to Peace Making, it would be easier to resolve conflicts if they had "not been accompanied by an intense socio-psychological repertoire, which becomes an investment in conflict and evolves into a foundation of culture of conflict. It is rigid and resistant to change, fuels its continuation, inhibits de-escalation of the conflict and thus serves as a major barrier to its peaceful resolution." Therefore, it is the psychological aspects that require greater focus. Some suggestions are enumerated below.

Engage with the Society: There has to be a genuine outreach to the society that is sincere and matches words with actions. Promises of great future economic benefits will cut no ice if the youth are suffering today due to an internet shutdown. The future cannot be built on the debris of today’s expectations. While engaging with the society, the aspirations of the other communities, including the Dogras, Kashmiri pandits, Ladakhis, and Gujjars and Bakerwals, must also be addressed.

Build Confidence Through Trust: In conflict situations, there is always an attempt by the government (past and present) to paint itself in a superior moralistic and nationalistic position. This requires the opponent to be demonised, and trust between the demonised citizen and the state becomes the first casualty. The restoration of this trust will require the government to address the exaggerated fear of loss of identity among the Kashmiris due to rumours about the resettlement of outsiders and political restructuring. It is also necessary to commence a dialogue between the different communities of Kashmir and Jammu to build confidence among them that no group is seeking political advantage at the expense of the other.

Unequivocal Communication: There is a need to clearly communicate that government actions are genuinely meant to ensure a better future for the people of Jammu and Kashmir. While the government has been at pains to point this out repeatedly, the political messaging from various interviews and election speeches hints at majoritarianism. This arouses suspicion among the Kashmiri Muslims and makes reconciliation difficult. To bridge this gap, a team of respected interlocutors could prove useful in accurately conveying information about the intent and motivations of the two sides.

Ensure Security: The well-being and security of common citizens is the responsibility of the government. Terrorists and their supporters will try and coerce people through acts of violence and intimidation, and it must be ensured that they do not succeed. While security forces, convoys and camps must be protected, it is equally important that there is greater security focus on preventing terror attacks on civilians, particularly non-locals. Attacking the terrorists' strategy pays higher dividends than attacking the terrorists.

Another issue must be clearly stated. In looking for the approaches towards conflict resolution in Kashmir, we cannot hold only the government responsible for its success or failure. The Kashmiri civil society, the local political elite, and ethnic activists must not harbor unrealistic expectations of autonomy or independence. It is now a commonly accepted international view that minority rights must be protected, but this cannot come at the cost of a nation’s sovereignty. The obdurate stand of the separatists in trying to involve Pakistan in matters that are purely internal, has hardened positions and caused immense harm to the Kashmiris themselves. Deep introspection is required by the political leadership, and the people of Kashmir, whether accepting some compromises for the reward of peace, is perhaps the best way forward.

We may agree or disagree with the government’s decision of August 5, but it has undoubtedly provided a trigger for fresh thinking on the Kashmir issue. The real test is whether we define success by a temporary absence of violence and the number of terrorists killed or by psychological healing of communities in conflict. The latter offers a more hopeful vision of the future.

(The author is former Northern Commander, Indian Army, under whose leadership India carried out surgical strikes against Pakistan in 2016. Views are personal.)

Comments

0 comment