views

US intelligence agencies are scrutinizing efforts by Saudi Arabia to build up its ability to produce nuclear fuel that could put the kingdom on a path to developing nuclear weapons.

Spy agencies in recent weeks circulated a classified analysis about the efforts underway inside Saudi Arabia, working with China, to build industrial capacity to produce nuclear fuel. The analysis has raised alarms that there might be secret Saudi-Chinese efforts to process raw uranium into a form that could later be enriched into weapons fuel, according to US officials.

As part of the study, they have identified a newly completed structure near a solar-panel production area near Riyadh, the Saudi capital, that some government analysts and outside experts suspect could be one of a number of undeclared nuclear sites.

US officials said that the Saudi efforts were still in an early stage, and that intelligence analysts had yet to draw firm conclusions about some of the sites under scrutiny. Even if the kingdom has decided to pursue a military nuclear program, they said, it would be years before it could have the ability to produce a single nuclear warhead.

Saudi officials have made no secret of their determination to keep pace with Iran, which has accelerated since President Donald Trump abandoned the 2015 nuclear deal with Tehran. Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman pledged in 2018 that his kingdom would try to develop or acquire nuclear weapons if Iran continued its work toward a bomb.

Last week, the House Intelligence Committee, led by Rep. Adam B. Schiff, D-Calif., included a provision in the intelligence budget authorization bill requiring the administration to submit a report about Saudi efforts since 2015 to develop a nuclear program, a clear indication that the committee suspects that some undeclared nuclear activity is going on.

The report, the provision stated, should include an assessment of “the state of nuclear cooperation between Saudi Arabia and any other country other than the United States, such as the People’s Republic of China or the Russian Federation.”

An article in The Wall Street Journal on Tuesday said that Western officials were concerned about a different facility in Saudi Arabia, in the country’s northwest desert. The Journal said it was part of a program with the Chinese to extract uranium yellowcake from uranium ore. That is a necessary first step in the process of obtaining uranium for later enrichment, either for use in a civilian nuclear reactor or, enriched to much higher levels, a nuclear weapon.

Saudi Arabia and China have publicly announced a number of joint nuclear projects in the kingdom — including one to extract uranium from seawater — with the stated goal of helping the world’s largest oil producer develop a nuclear energy program or become a uranium exporter.

Intelligence officials have searched for decades for evidence that the Saudis are seeking to become a nuclear weapons power, fearful that any such move could result in a broader, destabilizing nuclear arms race in the Middle East. So far, Israel is the only nuclear weapons state in the region, a status it has never officially confirmed.

In the 1990s, the Saudis helped bankroll Pakistan’s successful effort to produce a bomb. But it has never been clear whether Riyadh has a claim on a Pakistani weapon, or its technology. And 75 years after the detonation of the first nuclear weapon used in war — the anniversary of the Hiroshima blast is Thursday — only nine nations possess nuclear weapons.

But ever since the debacle of the Iraq invasion in 2003, based on faulty assessments that Saddam Hussein was restarting the country’s once-robust nuclear program, intelligence agencies have been far more reluctant to warn of nuclear progress for fear of repeating a colossal mistake.

At the White House, Trump administration officials seem relatively unperturbed by the Saudi effort. They say that until the Iranian nuclear program is permanently terminated, the Saudis will most likely keep the option open to produce their own fuel, leaving open a pathway to a weapon.

But now the administration is in the uncomfortable position of declaring it could not tolerate any nuclear production ability in Iran, while seeming to remain silent about its close allies, the Saudis, for whom it has forgiven human rights abuses and military adventurism.

Trump and his top aides have built close ties to the Saudi leadership, playing down the killing of the journalist and Saudi dissident Jamal Khashoggi and enlisting the crown prince in so-far fruitless Middle East peace efforts.

It also comes at a time when the Trump administration is aggressively taking on China on numerous fronts, like its handling of the novel coronavirus and its efforts to crack down on freedoms in Hong Kong. So far, the White House has said nothing about China’s array of nuclear deals with the Saudis.

Spokespeople for the National Security Council and the CIA declined to comment. A spokesman for the Saudi Embassy in Washington did not respond to a message seeking comment.

Late Wednesday, the State Department said in a statement to The New York Times that while it would not comment on intelligence findings, “we routinely warn all our partners about the dangers of engagement with the P.R.C.’s civil nuclear business,” referring to the People’s Republic of China, “including the threats it presents of strategic manipulation and coercion, as well as technology theft. We strongly encourage all partners to work only with trusted suppliers who have strong nonproliferation standards.”

The statement also said that “we oppose the spread of enrichment and reprocessing,” and that the United States would “attach great importance” to continued compliance by the Saudis to the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty. It urged Saudi Arabia to conclude an agreement with the United States “with strong nonproliferation protections that will enable Saudi and US nuclear industries to cooperate.”

From the beginning of his administration, Trump has conducted negotiations with the Saudis over an agreement, which would require congressional approval, enabling the United States to help Saudi Arabia build a civilian nuclear program.

But the Saudis would not agree to the kinds of restrictions that the United Arab Emirates signed onto several years ago, committing the country never to build its own fuel-production ability, which could be diverted to bomb production. Administration officials say the negotiations have been essentially stalled for the past year.

Saudi Arabia’s work with the Chinese suggests that the Saudis may have now given up on the United States and turned to China instead to begin building the multibillion-dollar infrastructure needed to produce nuclear fuel. China has traditionally not insisted on such strict nonproliferation safeguards, and is eager to lock in Saudi oil supplies.

Regional experts say part of the Saudi calculation stems from the view that the kingdom can no longer count on America’s willingness to counter Iran.

That view gained more currency in the kingdom after the Obama administration signed the 2015 nuclear deal with Iran, known as the JCPOA. It forced Iran to give up 97% of its fuel stockpile, but left open a path to production in the future.

“They believe that as a result of the JCPOA they can’t rely on anyone reining in the Iranians, and they are going to have to deter Iran themselves,” said Rolf Mowatt-Larssen, a former CIA officer and director of intelligence and counterintelligence at the Energy Department.

The irony, Mowatt-Larssen said, is that Saudi Arabia has sought both civilian nuclear partnerships and defense agreements with two powers — Russia and China — that have deep economic ties to Iran.

Saudi Arabia has spent years developing a civilian nuclear program, and has a partnership with Argentina to build a reactor in the kingdom. But it has rejected limits on its own ability to control the production of nuclear fuel and it has been systemically acquiring skills — uranium exploration, nuclear engineering, and ballistic missile manufacturing among them — that would position it to develop its own weapons if it decided to do so.

“It’s never been in doubt,” said Thomas M. Countryman, the assistant secretary of state for international security and nonproliferation from 2011-17. “They see a value in having a latent capability to produce their own fuel and perhaps their own weapons.”

The Saudis have been relatively open about their interest in developing the ability to enrich uranium, a radioactive element that is a main fuel of both power reactors and nuclear warheads.

Last year, a document titled, “Updates on Saudi National Atomic Energy Project,” posted by the International Atomic Energy Agency, or IAEA, in Vienna, detailed a plan for building civilian reactors as well as fueling them through the “localization” of uranium production.

The same document said the kingdom was looking for uranium deposits in more than 10,000 square miles of its own territory (an area about the size of Massachusetts) and had teamed up with Jordan to make yellowcake, a concentrated form of uranium ore. Its production is an intermediate step on the road to enriching uranium into nuclear fuel.

The facilities under intelligence scrutiny have thus far not been declared to the IAEA. The agency monitors compliance with the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, which Saudi Arabia signed decades ago.

“The IAEA is unhappy with Saudi Arabia because they refuse to communicate about their existing program and where it is going,” said Robert Kelley, a former inspector for the atomic agency and a former official at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California.

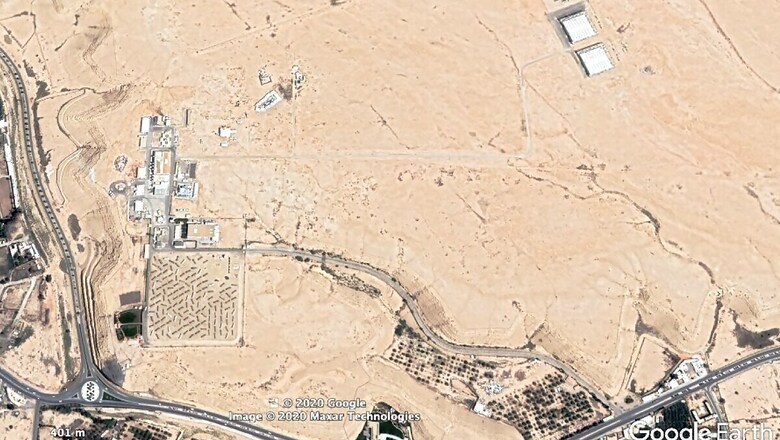

The site identified by U.S. intelligence as possibly nuclear in purpose lies in a secluded desert area not too far from the Saudi town of Al-Uyaynah and its Solar Village, a famous Saudi project to develop renewable energy.

David Albright, the president of the Institute for Science and International Security, a private group in Washington that tracks nuclear proliferation, analyzed commercial satellite images of the desert site.

In a five-page report, Albright described the facility, built from 2013 to 2018, as suspicious given its relative isolation in the Saudi desert and its long access road.

A satellite image taken in 2014, before the structure had a roof, he said, revealed the installation of four large yellow cranes for lifting and moving heavy equipment across sprawling high-bay areas. Albright added that each building also had adjoining two-story offices and areas for support personnel.

He noted that his examination of satellite images could identify no signs of processing equipment or raw materials arriving at the desert facility.

In his report, Albright found the appearance of the Saudi buildings to be roughly comparable to that of Iran’s uranium conversion facility, a plant that was designed by China in the city of Isfahan. It is central to Iran’s nuclear ambitions.

But Kelley expressed skepticism that the satellite images showed evidence of secret nuclear work. The Uyaynah site, he said, “has been identified for years as a joint U.S.-Saudi solar cell development facility.”

“That is exactly what it looks like in satellite imagery,” he said.

Still, Kelley added, “I am completely convinced that Saudi Arabia and China are actively cooperating on plans for uranium mining and yellowcake production” elsewhere in the kingdom.

Frank Pabian, a former satellite image analyst at the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, located a desert site that seemed to match the facility described in The Journal article. It appears to be a small mill for turning uranium ore into yellowcake. It has a checkpoint, high security fences, a large building about 150 feet on a side and ponds for the collection of uranium waste — a signature of such mills. The rugged desert site is in northwestern Saudi Arabia just south of Al-Ula, a small town once on the trade route for incense.

Satellite imagery shows that construction of the Al-Ula site began in 2014, roughly the same time facility work got underway near Al-Uyaynah.

Mark Mazzetti, David E. Sanger and William J. Broad c.2020 The New York Times Company

Comments

0 comment