views

Drafting a Compelling Story

Think of a short, visual story to translate from your head to the page. Comic books are a blast because they merge written words with cinematic images, blending the best of both novels and movies. Remember this when considering stories—you want something with big, fun images and visuals as well as a fair amount of conversation and dialogue. While there are no wrong ideas, some things to keep in mind include: Keeping the story visual: A conversation taking place in one room wouldn't work well since you won't have many new scene changes. A character musing to themselves might work, especially if the background reflects their changing thoughts. Streamlining the story: More characters, locations, and action are great, but it significantly increases the workload on the illustrator. The best comic books tell their stories quickly and efficiently, using both dialogue and visual cues to keep things moving. An Artistic Style: Great comic books have art that fits seamlessly with the tone of the writing, like the dirty, watercolor artwork in V for Vendetta. In short, the tone of the artwork should be the same as the tone of the writing.

Draft out the plot of your story in paragraph form. Just start writing, not worrying about form, content, or how it will look on the page. Once you have your idea down, get the pen flowing. Put the characters or ideas in motion and see what happens. If you throw 90% of this away, that is okay. Remember the advice of writer and animator Dan Harmon, who claimed that the first draft is 98% terrible, but the next one is only 96% bad, and so on until you have a great story. Find the 2% that's awesome and build off it: What characters are the most fun to write? What plot points did you find yourself most interested in exploring? Are there things that you thought were good ideas that you just can't write? Consider ditching them. Talk this draft over with some friends to get advice on what they love and how to go forward.

Create round, flawed, and exciting characters. Characters drive plots in almost all great movies, comics, and books. Almost all comics are the result of a character who wants something but is unable to get it—from villains trying to rule the world (and heroes trying to save it) to a young girl looking to figure out her complex political environment (Persepolis). The fun of any comic book, whether about superheroes or average Joes, is following a character's trials, tribulations, and personal flaws as they try to accomplish their goals. A great character: Has both strength and weaknesses. This makes them relatable. We don't like Superman just because he saves the day, but because his awkward alter-ego Clark Kent reminds us of our own awkward, nervous days. Has both desires and fears. This adds conflict to your story and makes it more interesting. It's no mistake that Bruce Wayne is scared of bats, just like he's scared of failing his city and parents. This makes him more relatable than a weirdo in a cape. Has agency. Whenever a character makes a choice, make sure it is the character deciding to do it—not the author forcing the character to do it because "the plot needs it." This is the quickest way to lose your audience. Remember to diversify your cast. We live in an age now where we want more diversity than standard—it doesn't have to be about race. You can diversify your characters about gender, sexuality, and age. Very often, we see the same types of characters all the time in particular types of roles, so try to avoid that.

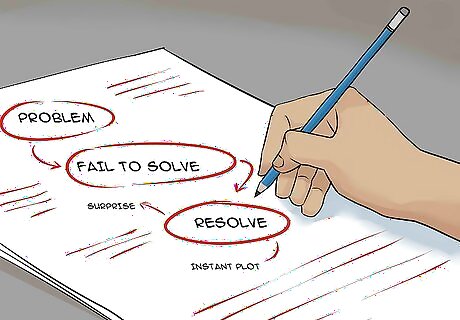

Introduce a problem, fail to solve it, and then resolve the problem with a surprise to create an instant plot. If this sounds too simple, it is. But it is the genesis of all plot. You have your characters, and they have a problem (The Joker is on the loose, the Avengers broke up, Scott Pilgrim got dumped). They decide to fix the problem and fail (The Joker escapes, Captain America and Iron Man start fighting, Scott Pilgrim has to fight 7 exes). In a triumphant final push, your characters finally prevail (Batman defeats The Joker, Cap and Ironman usher in peace, Scott Pilgrim gets the girl). These are your major plot points and you can play with them however you want. But knowing these three stepping stones ahead of time will save you a lot of writing headaches. "First act—Get your hero up a tree; second act—throw rocks at him; third act—get him down."—Anonymous Make life hell for your characters. It makes the payoff more rewarding. You can and should always play with this structure. Don't forget that (spoiler alert) Captain America gets assassinated shortly after peace is brokered in Civil War. This moment is great because it plays off the three-act structure, even as it breaks it with a second, surprising climactic moment. If you want to make your story around a mystery, tension is one of the key elements you need to add. It's also important to make it compelling from the beginning. Mysteries are very plot heavy, so they usually begin with some sort of crime or question that someone has to answer.

Whenever possible, convey information visually instead of through dialogue or exposition. Say, for example, you have a character who needs to turn a paper in or they fail their class. You could have the character wake up and tell their mom "I need to turn this paper in or I fail." But this is simple and unrewarding to the reader. Consider a few ways to tell this same plot point visually: A page of illustrations where the character frantically runs through the door, down the hall, to the office, and then finds it "Closed." A sign on the wall labeled "Final Papers Due TODAY!" that the character walks right by when leaving class. A single shot of every other student turning in papers, with your character alone at the desk writing furiously, or with his head in his hands.

Using your drafts and paragraphs, create timelines for the action and characters in your story. Try to be really methodical about this, boiling down each plot point and action into it's essential moment. Think of these as each page of the comic book. You want the story to be progressing with every flip of the page. What is crucial in each scene? What moment or line of dialogue pushes each scene into the next. In any storytelling form, each scene must end in a different place than it began for the readers, plot, and/or characters. If not, then the whole book is just spinning its wheels!

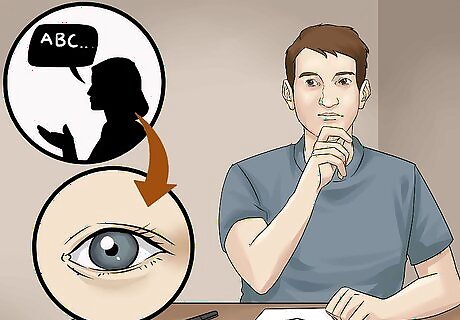

Fill in the dialogue, work shopping it with friends to make it realistic. Finally, once the story and characters are in place, it's time to nail down the dialogue. The trick is to make each character sound as human as possible, but there is actually an easy way to do this: have humans read out each character. Invite over 1-2 close friends and read through the dialogue like a script. You'll hear instantly when people can't quite get the words out or sound unnatural. There is nothing that says you can't write dialogue first, either! If you like play-writing or screenwriting, you may be more comfortable drafting out scenes in dialogue as opposed to timelines.

Building a Mock-Up

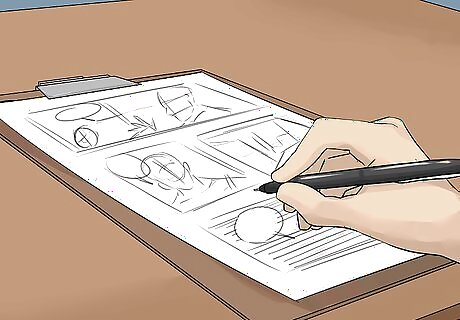

Use a mock-up to test out your ideas, style, layout and pacing without sinking too much work into the idea. A "mock-up" is basically a sketch of the entire comic book, page by page. They don't have to be detailed as the bigger issues layout. Instead, figure out how many frames or lines of dialogue fit on each page, where do you want any "special pages" (like full-page frames), and will the format of each page be identical or change depending on mood? This is where you start merging the words to the pictures—so have some fun. If you're not artistically inclined, you don't need to worry about hiring an artist just yet. Instead, just focus on the basics. Even stick figures can get the point across and help your visualize the final book. While this is "only" a mock-up, you still want to take it seriously. This will be your blueprint for the final project, so treat it like a sketch for a painting and not some throwaway practice run.

Create several timelines: one for what should be shown to the reader in the story, what action needs to occur, where character development will go, etc. Other timelines will need to be made for each character, so you know what their life has been so far, where it is going, etc. These will help you keep the pages and stories straight, visualizing where each character needs to be at each portion of the book.

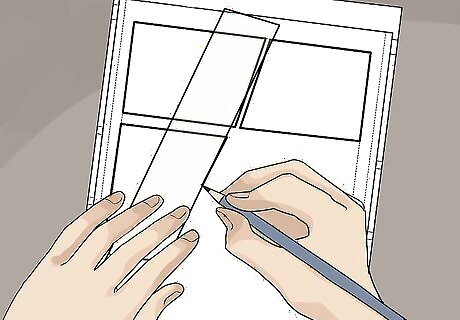

Divide a blank page into panels for your story. Keep in mind pacing, so if your main character has just discovered the bones of a monster in her backyard, the reader gets to have a nice big picture to look at and take their time viewing.

Using your timelines as a guide, fill in the panels with either descriptions or sketches of what action should be seen, and what dialogue should be heard. Remember that dialogue is actually seen in a comic book, so it literally needs to fit in each box. Try not to jam too much at once. That said, some comic books choose to let the dialogue balloons spill into other frames, creating a somewhat looser, chaotic feel. For longer speeches or monologues, consider connecting the speech bubbles from frame to frame. The same person is giving the same speech, just with different action underneath.

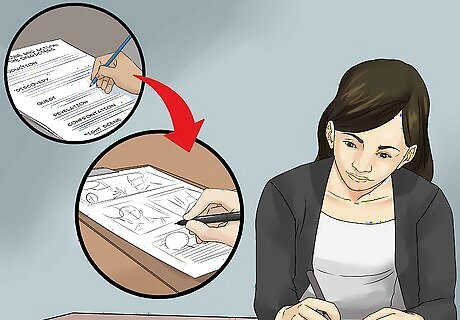

Keep your script page and graphic page side by side as you work. Many professionals will use two pages, one for the script and one for the pictures. Remember, the trick of comic books is your balance between words and visuals, and this is easiest to see side-by-side. You can tick off each caption and frame as you work. For example, the script might go: [Page 1.] Spiderman is swinging down the streets when he spots 2 police cars chasing a yellow sports car. Caption1: Hmm it's strangely quiet today... Caption 2: I guess I spoke too soon! [Page 2.] Spiderman is swinging down the street and the two blank caption spaces.

Hire an artist, or finish the work yourself, once you're happy with the mock-up. If you've been diligent about clean professional work, you might be able to turn the mock-up itself into the book. Otherwise, get to work on the actual thing, using your mock-up as the guide. Sketching, inking, and coloring a comic book is a serious undertaking. But it is also a ton of fun. If you're getting an outside artists, send them the script and ask for samples. This helps you see if their visual style is right for you. Illustrating a comic book is a topic worth its own tutorial, as it is a challenging and exciting art form.

Getting Your Book into the World

Consider starting a free webcomic to build interest and buzz. The internet age gives you endless opportunity to market and publish your own work that should not be discounted. In many ways, shorter internet comics have replaced physical comics books as ways to build towards the inevitable graphic novel, which is usually all of the strips collected in one book. Even better, use your webcomic to expand on the stories or characters in the book, enticing viewers to buy the "real thing." Getting up on social media every day, even if only for 20 minutes, is essential to build some traction online and get potential readers. If you can point to a large follower list, on any platform, publishers are more likely to see and like your work. Having followers tells them there are people already who want to buy the book.

Make a "hit-list" of comic book and graphic novel publishers with work similar to yours. Look up the authors and publishers of your favorite comics, leaning towards ones with a similar tone or subject as your comic. Be sure to branch out, too -- this list cannot be too big! Remember that, while working for Marvel or DC would be a blast, it is very rare for first-timers to get picked up by the big guys. Independent and smaller presses are a much better bet. Get contact information, including email, website, and address, for every company. If applying for graphic novels, be sure to check if the publishing house has a specific division for graphics work, or if they take all submissions the same way.

Submit samples of your work to your target publishing houses. Head online and see if the house accepts "unsolicited submissions," meaning you send them the work even if they don't ask. Read all the rules and guidelines, then send in your absolute best work. You won't hear back from everyone -- but that is why you keep the list as big as possible. Any cover letters or emails should be short and professional. You want them reading about the story, not about you! Make sure artistic samples are included with the story.

Consider self-publishing and marketing your book. It's a daunting task, but doable. Printing may get expensive, but you get complete control over the entire book, ensuring that your vision gets onto the page unfiltered. To self-publish a comic book, simply create a PDF from the pages using Amazon Self Publish or a similar site.

Understand off the bat that the world of publishing is not always easy or fair. There are so many manuscripts that hit the desks of publishers that many are thrown out without being read. This isn't to discourage you -- many amazing books get through, too! -- but rather to prepare you for the hard work ahead. Having a book you love and feel proud will make the slog of publishing much, much more bearable. Don't forget that even the most famous authors were rejected 100's of time before success. It may hurt now, but working through it separates published comics from unpublished.

Comments

0 comment